This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For Jordan Ridge Elementary school teacher Alison Richins, helping her students learn math wasn't a matter of filling her classroom with computers loaded with cutting-edge software.

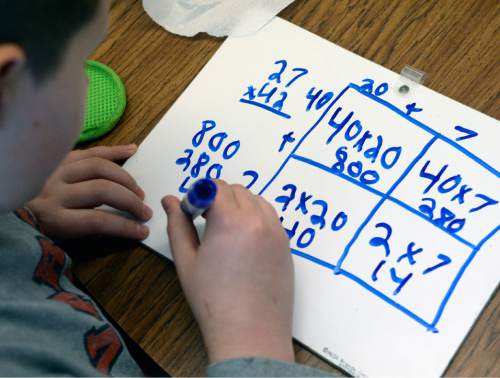

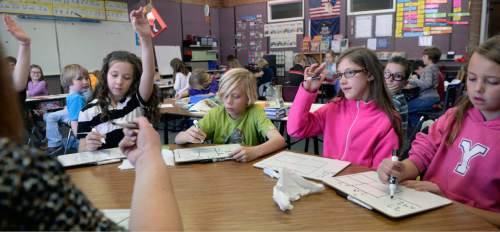

Instead, she purchased 30 whiteboards and began observing her students work through problems.

"It allows me to see who understands and who doesn't," she said Tuesday. "I can work with those students one-on-one later."

Richins' low-tech solution came with a price tag of more than $200 for a classroom set, too much for her scant supply budget.

But thanks to a $500 grant from the Jordan Education Foundation, which raises money on behalf of the Jordan School District, Richins was able to purchase her whiteboards and other simple classroom supplies. "That's not anything that I can just do on my own," she said. "For me, it's made a huge difference."

The foundation hopes to make an even greater impact in the district this year. Organizers launched a public fundraising campaign Tuesday aimed at generating $1 million in community donations in 90 days.

Ambitious campaigns for donations are common at colleges and universities, but are less frequent at the school district level. While most districts have a corresponding education foundation, their work is typically done behind the scenes, encouraging academic support from individuals and businesses.

But Steven Hall, executive director of the Jordan foundation, said the gap between classroom needs and taxpayer funding results in too many educators either going without supplies or dipping into their personal finances.

He said the foundation's $1 million goal is particularly challenging, with the group typically raising between $400,000 and $600,000 in unrestricted donations each year.

"It's virtually doubling what we do in a year in 90 days," he said. "It's aggressive, but I think all of us working together, everyone doing a little bit, we can make it happen."

Richins has received three grants from the foundation. In addition to the whiteboards, grants have allowed her to buy nonfiction books and learning games for her students.

But even with those grants, Richins said, she has to pay out of her pocket to supplement classroom funds. During a single school year, she spends between $200 and $800 of her own money on classroom supplies.

"I think [people] think their taxes pay for everything that school includes and it doesn't," she said. "I've spent a lot of my money to be able to teach the way I think I need to for the kids' benefit."

In addition to classroom grants, Hall said, the foundation has helped schools set up food pantries for families living in poverty and greenhouses for science classes. The donations have been used to pay for eye examinations and glasses, art and music supplies and to bolster science, technology, engineering and mathematics learning, collectively known as STEM.

He said educators do a good job with the funding they receive from taxpayers. But in many cases, extra funding can make a significant impact on student learning.

"Simply said, the tax dollars aren't covering it," Hall said. "Our teachers deserve more and our students deserve more."

Jordan School District Superintendent Patrice Johnson said that unlike state funding for education, which is largely used for teacher salaries, the money from community donors is delivered directly to classrooms for learning programs and supplies.

"The way the state raises revenues for education is minimal," he said. "If you want to provide the minimum for students we can certainly do that, but really in our area we want to provide and meet the individual needs of students rather than just providing the basics."

But Sharon Gallagher-Fishbaugh, president of the Utah Education Association, said that turning to residents for $1 million in donations isn't a long-term solution or a feasible option for many of the state's small and rural school districts.

She also said it's "pathetic" that teachers are forced to spend hundreds of dollars of their own money on school supplies.

Gallagher-Fishbaugh commended the Jordan foundation and Jordan residents for their efforts to help teachers. But she added that the campaign is indicative of state leaders shirking their responsibility to fund schools.

"We need to demand a better funding mechanism for public education," she said. "I'm not talking about excessive funding. I'm talking about adequate funding."