This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In the back of a tidy split-level Glendale home, Merrill Taliauli gazes up at a giant flat-screen television and flips between a pair of college basketball games. The 17-year-old cares little about either. His father, Toni, played hoops in college, but it never was Merrill's game.

His love was football. Always football.

Merrill was 8 the first time he pulled a red-and-white East High Leopards jersey over his pads. That fall, his father stood on the sidelines, motioning to his son the moves he should use against opposing linemen, all the while beaming. His mother, a teacher, worried about her son's safety until she saw him tackle; then she worried about the other boys.

The game is "in his blood," his father says, just as it's in the blood of many Polynesians from Merrill's Salt Lake City neighborhood. Ricky Heimuli, a rising star at Oregon, grew up just down the street. Simi Fili once accepted an offer to play for the Ducks, too. Nate Fakahafua starts for the University of Utah. Stanley Havili plays for the Philadelphia Eagles now.

Utah's college football programs have long turned to small islands in the south Pacific for gridiron stars. But decades after opening up the Polynesian pipeline that began reshaping college football in this state, the young men and families who moved here from Tonga, Samoa or Hawaii have put down roots.

The result: a level of high school football that Utah has never before experienced, and a pool of local Polynesian talent that has transformed the state into a must-stop recruiting ground for colleges across the country.

—

"Uniquely gifted" • Proselytizing Mormons first visited the Polynesian Islands in the mid-1840s. About 170 years later, football coaches, like missionaries with whistles around their necks, returned to the islands promising a more temporal glory.

Players and coaches call former Utah and Weber State coach Ron McBride "the Godfather." Famika Anae, father of BYU offensive coordinator Robert Anae, arrived in Provo nearly 50 years ago. Since then, more than 100 Samoans have played for the Cougars.

"I don't think it's overstating it," said Vai Sikahema, a member of BYU's 1984 national championship team, "to say that the impact Samoans and Tongans have had in the state of Utah is not unlike what Dominicans have been to baseball."

Sikahema, who went on to become one of the first Tongan players in the NFL, believes Polynesians are "uniquely gifted to play American football." He cites a culture that respects authority, traditional dances that develop rhythm and nimble feet, and natural muscularity as reasons.

"They say Polynesians are bred to play it," Woods Cross linebacker and Utah commit Filipo Mokofisi said, "and I fully believe in that."

Mokofisi, who shares a first name with his father, is one of several sons of former players who have helped elevate Utah prep football in recent years.

When Dave Peck took over Bingham's football program in the early 2000s, he had one Polynesian player on his roster. At that time, Peck expected to see only a handful of Utah players get scholarship offers from major Division I schools. But over the past decade, Utah has begun to blossom into an important recruiting stop. Although it is not Texas, Florida or California — the country's recruiting epicenters — major college programs no longer overlook it.

"Utah is absolutely must-recruit territory," said Erik McKinney, ESPN's West recruiting coordinator. "You have to know who is in Utah at this point."

On National Signing Day Wednesday, more than 40 (and as many as 60) Utah high school seniors will sign letters of intent to play football for Division I programs. Nearly half of the top 40 prospects are of Polynesian descent.

"Utah started to go from a novelty-type state to a legitimate state," said Brandon Huffman, Scout.com national recruiting analyst. "You could probably start to say Utah is rivaling Arizona as the second-most-fertile recruiting state in the West. And pound for pound, I might say Utah is putting out better depth."

This year, Peck counts at least a dozen of his former players at Utah State, BYU and Utah, including Star Lotulelei, a projected first-round NFL pick. This week, six of Peck's players will sign letters to play D-I football, headlined by Lowell Lotulelei, Star's younger brother.

—

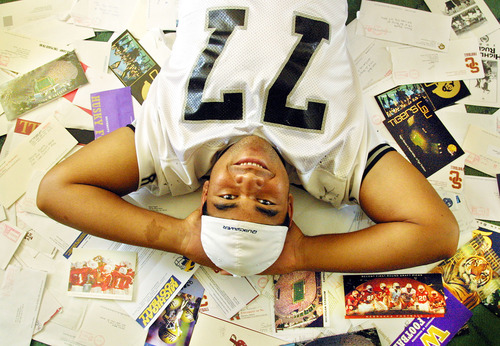

"They were huge" • This rise did not happen overnight. In fact, Merrill Taliauli, who just completed his senior season at East, hardly has noticed it. He's been part of the groundswell his entire life.

The defensive tackle, described in one ESPN report as a "big strong kid who can be a stout presence in the heart of the trenches," takes up most of a love seat. He turns off the games he is watching and presses play on a nearly decade-old highlight video. He and his father laugh at the miniature Leopards scampering across well-worn fields.

"That's me," Merrill says, pointing to the smallest lineman on a team so big it had to play up a grade in tournaments.

In one highlight, Merrill grabs a running back, spins him and throws him to the ground. In another, he pulls from his spot on the offensive line and blocks downfield for Sione Palelei, now one of Louisiana's top running-back recruits. There's a quick shot of John Fakahafua, the East wide receiver who has committed to Utah State.

Merrill learned early on he could compete outside Utah. His Leopards traveled to Las Vegas four times to play tournaments against teams from across the country.

That first year, Merrill remembers, the boys were intimidated by a team called the Raiders, who were all dressed in matching sweat suits as they arrived for the game.

"They were huge," Merrill said.

"Our guys looked like the Bad News Bears," his father recalled.

But in the first quarter, Merrill hit the Raider quarterback, knocking him out of the game. A big trophy now sits in Toni's office — representing one of four championships the team won in five undefeated seasons.

—

"I got a huge hit" • When he watched last month's Fiesta Bowl, Bountiful High assistant coach Alema Te'o instantly saw familiar faces.

Brighton High's Ricky Heimuli anchored Oregon's defensive line. When the ball changed hands, Te'o spotted West High's Vai Lutui in the purple and silver of Kansas State.

Te'o, great-uncle of Heisman trophy finalist Manti Te'o, founded the annual All-Poly Camp at Bountiful and sees what his camp nurtured in nearly every college game.

Brandon Fanaika attended the camp before Stanford landed him as Utah's top recruit of 2012. Other coaches have taken notice, too.

"Over the years, I've seen how football has gotten better in Utah," Stanford assistant coach Lance Anderson said. "There are more prospects each year."

As the camp approached last summer, Merrill Taliauli was unsure he would be able to attend. He had broken his toe but decided to push through it.

The camp attracts about 400 Polynesian players, mostly from Utah, and it has grown so much in recent years that Te'o has had to move it from Bountiful to Layton High. The camp also draws some of the nation's top coaches. New Wisconsin coach Gary Andersen sent Te'o a text to make sure he would have a spot at the camp.

Merrill found himself on a team so bad they weren't allowed to scrimmage until the last day against a team stacked with three- and four-star recruits. Merrill broke through the O-line and grabbed the quarterback for a sack, then another.

"I got a huge hit," he said, "and I saw a couple coaches turn their heads."

Utah State, Hawaii, Central Florida, Arizona — they pulled him aside. How much did he weigh? What other offers did he have? They promised to call him.

—

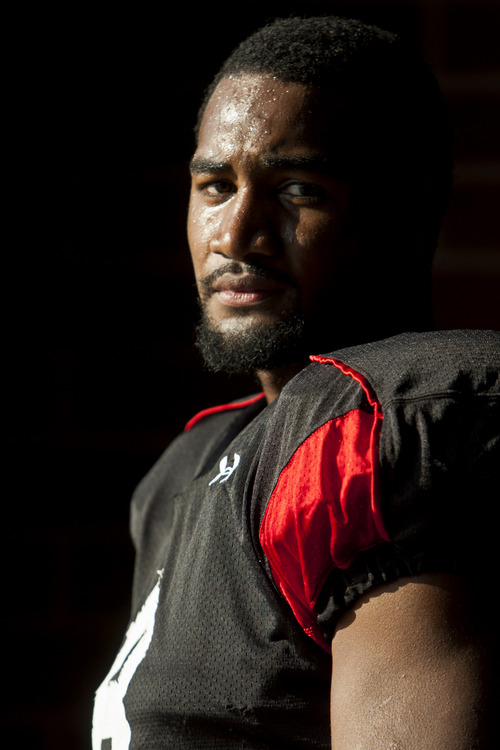

"He's crazy good" • Ask a young Polynesian football player, especially a defensive lineman such as Merrill, who his favorite athlete is, and one name comes up more than the others.

Haloti Ngata was the top-ranked defensive player coming out of Highland High School in 2002. Merrill's eyes transfix on Ngata when he watches the Baltimore Ravens play.

When a network puts a mic on the big defensive tackle, Merrill loves everything about it — the way he beats double teams, how he cracks jokes and helps players off of the ground, the way he helped the Ravens to the Super Bowl.

"He's just a good guy," Merrill said. "And how he plays, with tenacity. He's crazy good."

Growing up in Salt Lake City, Ngata said he thought of football as "a way out" of a lifetime of trouble or even just construction work. And to do that, he thought that he had to leave Utah.

"There was pressure to stay home because my mom wanted me to," Ngata said. "I always thought if I stayed in Utah, I wouldn't have made it past college. I thought if you stayed in Utah to play football, you were just going to be another Polynesian football player and be done."

Whether Ngata truly had to leave Utah to become an NFL prospect is debatable. But his decision to play at the University of Oregon impacted future recruiting.

"There's now more of an expectation that you can get a kid out of Utah," Scout.com's Huffman said. "Haloti Ngata is probably the most important recruit to ever come out of the state."

—

BYU scholarship • With his toe still broken, Merrill opted to skip a camp at the U. of U. But he wouldn't let himself miss a camp a few days later at BYU.

His father, Toni, went to BYU-Hawaii. His mother, Sisilia, earned her master's degree from the U. And on fall Saturdays in the Taliauli house, the girls wear red, the boys blue.

The morning of the BYU camp, Merrill said, he felt surprisingly good — maybe 80 percent healthy. That day he hustled through drills, and when it came time for one-on-one battles, Merrill shined.

BYU coach Bronco Mendenhall offered him a scholarship. Merrill accepted on the spot.

—

More than football • Sisilia Taliauli was born and raised in Tonga. She met Toni, who was born in Tonga but raised in Salt Lake City, when he was serving an LDS mission on the island.

The daughter of teachers, she went on to teach middle school herself. She was lucky that way, she said. So often on the island, the children of farmers become farmers.

She loves watching her son play football, but she's more proud of his 3.8 grade-point average.

"It has to be balanced," she said. "They're very talented on the football field, but we have to remember why we came from so far away: opportunity and education."

For this generation of Polynesian players, education has created an opportunity. In the past decade, Polynesians have seen increases in median income and college attainment. High school dropout rates, meanwhile, have fallen and now are on par with the state average.

The stability has helped more students focus on education. In turn, they can qualify for football, coaches said.

"Like any culture or group that comes into a system, it takes a couple of generations to figure it out," Alema Te'o, the Bountiful assistant coach, said.

Merrill is too young to remember how his parents juggled him and his siblings while attending classes, but it's a sacrifice he is old enough to respect.

"Polynesians have a lot of will because of where we came from," Merrill said. "We want to give back to our parents, especially getting a full ride."

Former Bingham standout Doug Fiefia never was going to escape football. His uncles were All-Staters at Kearns High in the 1980s, and his cousins were standouts at Utah State.

But it was Fiefia's brother, 10 years his elder, who got him into pads.

"I kind of didn't have a choice," he said. "He taught me everything he knew growing up. I was the little brother who had to run sprints and throw the football and do tackling drills with him. There was no doubt in my mind I was going to be a football player. I think that's very similar with most Polynesian boys."

Doug Fiefia introduced the Haka, a traditional dance once performed by warriors, to coach Peck in 2005 — that same year, Fiefia was the first Polynesian student body president to lead the Miners. And while football helped Fiefia get to college and focus on grades, he warns of the danger of overreliance on the sport.

"Polynesians have depended too much on football," said Fiefia, who walked away from the game with eligibility still left at Utah State. "It's hard to overlook the natural talent and abilities and the size their children are given. But it's been hard to get them to focus on the schooling and the books and their studies. That's what they're good at [football]. That's what they're comfortable with."

Former Herriman and Highland coach Larry Wilson says he's starting to see a shift among his players.

"For so long, you either read about them as a football player or a gang member," Wilson said. "That's changing. We're seeing within the culture acceptance of other things. Not every Polynesian boy has to be a football player to be successful."

—

"It's like two different games" • When a young lineman walks into his office at Herriman High, Wilson hits him with a pop quiz. Kailisi Moli lives in West Valley City but came to Herriman through the state's open enrollment policy. Too many of his cousins had dropped out of Cyprus High, he said. Now Wilson wants the sophomore to tell him what he needed to do to be ready for next season.

"Work out. Keep my grades up."

"Or his mother will whip him," Wilson says with a laugh. "And the last thing?"

The last thing is to make a highlight tape and send it out to colleges.

"He will get some interest already," Wilson, who teaches a course on how to be recruited, says of his sophomore.

Football in Utah has come a long way since he started coaching in the 1980s. "It's like two different games," he said. And the future is bright.

Huffman, the recruiting analyst, sees next year's recruits as a "pinnacle class" for the state.

"There are six guys who are already in our early [list of the top 300 recruits in the country]," Huffman said. "That's kind of unheard of for Utah. And that doesn't take into account guys who are really going to start to blossom."

—

Seeing the future? • Framed newspaper clippings of Merrill, the All-Stater, hang on a wall in the back room of the Taliauli house. In a corner opposite the gurgling aquarium are photographs of Merrill's senior season. There's Merrill sacking Timpview's quarterback on a snowy day in November, and Merrill in Mountain View's backfield, blowing up another play.

"It takes a few people to stop him," says Toni.

The room is Merrill's sanctuary, where he comes after school. It's where he and his teammate and best friend since kindergarten, Patrick Palau, often went to study playbooks and talk football. Palau, an East linebacker, will play fullback for the Cougars.

The room is where, after Merrill is gone, Toni and Sisilia will sit on Saturdays and watch on TV their son and his friends play. It's where the family will gather to watch today's Super Bowl — with Highland's Ngata in the middle of the Ravens' defensive line, and East High's Will Tukuafu wearing 49er gold and red as a fullback and defensive end.

The glow from the big screen will shine on a framed poster of Merrill and the rest of his young teammates.

Twitter: @aaronfalk,@chriskamrani

Kurt Kragthorpe contributed to the reporting of this story.