This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In 2005, Tooele County wanted nothing to do with a new state prison.

In fact, it was "highly resistant" to the idea, a consultant said in a report on the feasibility of moving the Utah State Prison

Today the county has made a complete about-face. The Tooele County Commission passed a resolution in February expressing interest in becoming the prison's new home.

What's behind that course change? Tough economic times — due primarily to the shutdown of the Deseret Chemical Depot, which will be complete in July.

"We have been proactive for several years in creating an interest and being prepared to talk about this," said J. Bruce Clegg, Tooele County Commission chairman.

Despite its initial resistance, Tooele surfaced as the ideal spot for a new prison in the past. But it likely will have competition from other rural counties that view taking more state inmates and relocating the prison from Utah's urban corridor as ways to bolster their economic stability.

"Counties are making a strong play for this," said Sen. Scott Jenkins, R-Plain City, who shepherded the prison-relocation bill through the Legislature.

In addition to Tooele, Sanpete and Juab counties are interested in the project. Meanwhile, counties that currently house state inmates are pushing for greater use of their jails as a way to downsize any new prison facility.

—

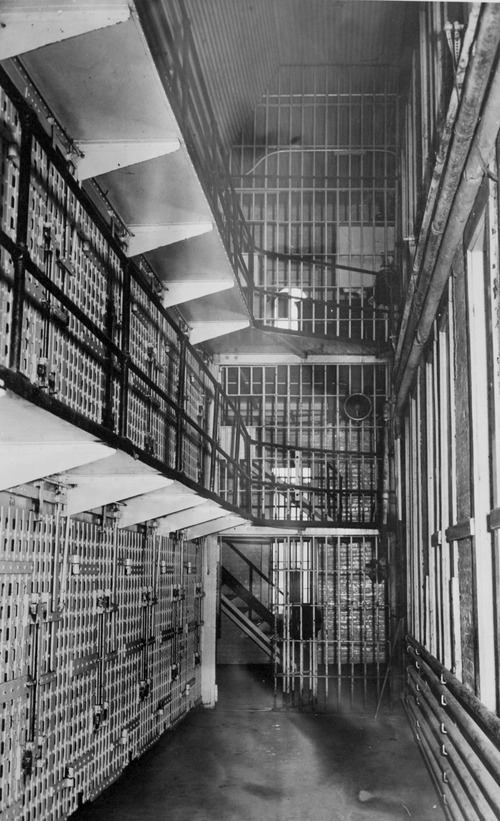

A prison town • Several national studies during the past two decades have shown little economic benefit for small communities that host a prison, but that hasn't kept prison facilities from being pitched as economic development tools. In a 2003 analysis, The Sentencing Project cautioned that the jobs and hoped-for economic benefits often don't materialize.

That point also was made in a 2005 evaluation of relocating the prison by Wikstrom Economic and Planning Consultants, which noted a literature search did not find "any major" economic development gains in communities that host prison facilities. The Wikstrom report said, however, that in rural areas "with few employment opportunities and low wages, prison jobs offer better-than-average wages."

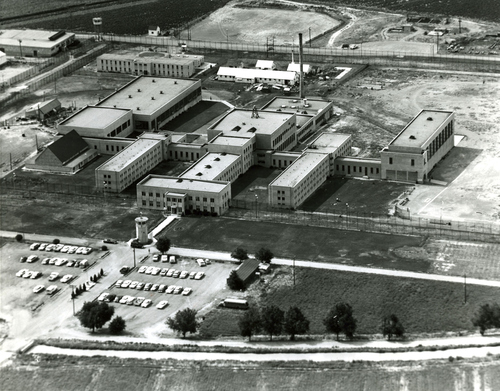

Gunnison Mayor Lori Nay said that's definitely been true for her Sanpete County community, which since 1990 has been home to the Central Utah Correctional Facility.

Nay said the prison has provided good-paying jobs for residents, and the city's police department has been able to draw on correctional officers who are state-certified to fill part-time jobs. According to data provided by the Utah Department of Corrections, about 51 of the facility's 335 employees live in Gunnison. The rest commute from such cities as Manti, Ephraim and Richfield; a small number of employees drive from as far away as Payson, Lehi, even Heber City.

Sanpete County Commissioner Jon Cox said the correctional facility has a payroll of around $8 million. Some of that money is spent locally, he said, and while many workers commute from surrounding locales, the county did see a population increase after the prison was built.

"It has definitely helped the southern end of the county," Cox said, a plus given that "we are one of the counties in the state that struggles with wage growth and employment."

Unemployment in Sanpete County hovers around 8 percent, more in line with the national than the state average, he pointed out.

On the downside, the facility has placed more demand on Gunnison's water system than expected, Nay acknowledged, and local businesses haven't seen much benefit.

Still, "it is a stabilizer to the local economy," said Nay. "Like with any business, especially one that is large in comparison to your community, there are challenges you face, but overall we've faced those pretty well."

Nay said the prison provides an outlet for residents who want to volunteer. Inmates, in return, reciprocate by doing yardwork at the city cemetery and making handmade pinatas for the community's Dairy Days Heritage and Cinco de Mayo festivals. Over all, Gunnison hasn't experienced any stigma, she said.

"If you were to ask anyone in Gunnison if they lived in a prison town, they don't look at it that way," she said. "It isn't part of our everyday life at all. It's a very clean industry in our town, and it doesn't [intersect] with the social life here, so it's not something we think about."

In fact, the city and the county, according to Cox, want the state to expand the facility.

"They had promised 2,100 beds and we're still at 1,600 beds," Nay said. "Every time the Legislature gets the opportunity to expand it, they turn it down."

During the recent session, a proposal to add 192 beds in Gunnison failed.

"I don't think it would make sense to have the [prison] down here," Nay said. "But to expand at least to 2,100 or add another 1,000 prisoners, people here regionally would appreciate that."

Cox said one idea worth discussing is converting the Gunnison facility to house high-security inmates and sending others to county jails.

—

A win-win? • As it is, rural officials throughout the state also are pushing to get more state inmates, said Brent Gardner, executive director of the Utah Association of Counties.

Lawmakers appear to support that idea, overwhelmingly passing a resolution this session that urged more use of county jails as a cost-saving alternative to building a new, all-level security prison — estimated in December at $550 million to $600 million.

"We have a lot of counties that house prisoners on contract with the state that want to propose the state downsize the Utah State Prison from its current size," Gardner said.

A new prison of up to 2,500 beds could be built just for maximum-security and special-needs inmates, and "anybody else could be sent out to the counties in a way that will save the state money," he said.

At present, 20 counties contract to take state inmates. Gardner said the counties estimate the arrangement saved the state as much as $19 million in 2012.

Steve Gehrke, spokesman for the Utah Department of Corrections, said while there are undoubtedly savings, that figure is too high and oversimplifies a complex calculation. The state picks up ancillary costs — medical and transportation expenses, for example — for inmates at county jails.

"While this certainly does not eliminate the savings," Gehrke said, "it significantly narrows that gap."

Still, Garfield County Commissioner Leland Pollock, chairman of the association's joint jails committee, figures savings could double if the counties — which currently have about 1,100 empty jail beds — took on more state inmates. He also said several counties are prepared, at their own cost, to add beds — even a small new facility of about 300 beds — if needed to accommodate Corrections' needs.

"There are several counties that have agreed, if we are given a 30-year contract, to build additional beds immediately," Pollock said, including some along the Wasatch Front.

"It's a win-win for the state," Pollock said. "The state doesn't have to use its bonding capacity, it doesn't have to use state taxpayer revenue and at the same time, the counties would get a [guaranteed] contract and be able to build additional beds at no cost to the state."

As important as the savings, he said, is the success counties have had in rehabilitating prisoners.

"It is much better in a county facility," he said. "The sheriffs are going to get it right. ... We are going to be a lesser cost to the state than the private sector, and our recidivism rate is going to be much better."

The Utah Sheriffs' Association gave the county proposal a unanimous endorsement in March.

While it did not pinpoint possible locations for a new prison, a 2009 report commissioned by the Utah Department of Corrections identified Rush Valley as a "clear winner" based on available state land, travel distances to courts and medical facilities, and proximity to a sizable workforce. Other contenders in the study, also done by Wikstrom, were eastern Box Elder County and northeastern Juab County.

Juab County Commissioner Chad Winn confirmed his county is interested and has conveyed that to Gov. Gary Herbert. Commissioners have identified sites west of the Mona Reservoir and in Dog Valley near Nephi as potentially suitable locations for a new facility, but the county hasn't yet done any in-depth studies, Winn said.

Tooele County didn't like the site the Wikstrom study zeroed in on because it was in the middle of elk calving and livestock pastures, and Deseret Chemical was still in full production destroying weapons, Clegg said. But it does agree Tooele is ideal. Its preferred site: land accessed from what's known as the Timpie Exit on Interstate 80, near the northern edge of the Stansbury Mountain Range.

"That is the best place to put it in our county," Clegg said. "The problem with other counties is transporting of prisoners through highly populated areas, but we don't have that issue."

There's no doubt Tooele County could use the economic lift — whatever its size — that would come with a new prison. The county is struggling financially because of reduced mitigation fees from Deseret Chemical and associated businesses. In 2012, those fees were $3 million less than the previous year.

Twitter: @Brooke4Trib Counties, rural officials jostle for a seat at the table

Utah Gov. Gary Herbert has not announced who will serve on the reformed Prison Relocation and Development Authority board, but counties and rural officials are pushing hard for a seat at the table.

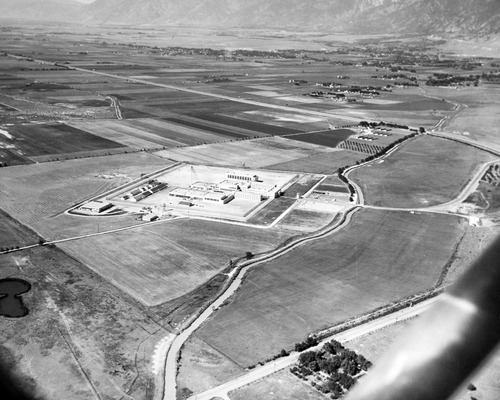

Herbert will appoint six of the 11 members, who will be tasked with seeking bid proposals for relocating the Utah State Prison and redeveloping the 690 acres it currently occupies in Draper. Leaders of the Senate and House will each appoint two members. Draper will get the final seat.

On Friday, Senate President Wayne Niederhauser, R-Sandy, said he had appointed Sens. Jerry Stevenson, R-Layton, and Stephen Urquhart, R-St. George. Stevenson is co-owner of J&J Nursery; Urquhart is an attorney.

Brent Gardner, executive director of the Utah Association of Counties, said counties have multiple stakes in the process — from how the existing site is redeveloped to where a new prison is located and how that potential move affects the Central Utah Correctional Facility and county jails that now take state inmates.

Said Gunnison Mayor Lori Nay: "So many people are clamoring to be on the board, but 47 percent of all prisoners in the state are held in rural Utah, and rural Utah doesn't get representation on these boards very often. We're hoping the governor understands [that] when he appoints these six members to the board."

Brooke Adams