This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A device developed by a group University of Utah students could have leeches checking the want ads.

The wormlike parasites have been sucking the life back into patients for millennia, and they're still on call at many U.S. hospitals. Until recently, at least, they're simply better than anything humans can make at reducing fluid pressure and injecting anti-coagulants into wounds after tissue reattachment surgeries and skin grafts.

But though they work without complaint, they're surprisingly expensive — about $1,200 per treatment — and what's more, they're just darned icky. Every 30 minutes or so, they'll slip off their intended target and begin unwanted leeching elsewhere. They can also trigger a bacterial infection.

So when, for their senior capstone project, U. mechanical engineering undergraduates Scott Ho, Jessica Kuhlman and Andy Thompson, helped developed a mechanical version, at least one nurse expressed her strong support.

"She said 'I'm so glad you're doing this because I hate dealing with these leeches. They're slimy, they stick on you when you try to put them on patients, and I just don't like them,'" said Kuhlman, who graduated in May and herself didn't realize leeches were still used in the United States until working on this project.

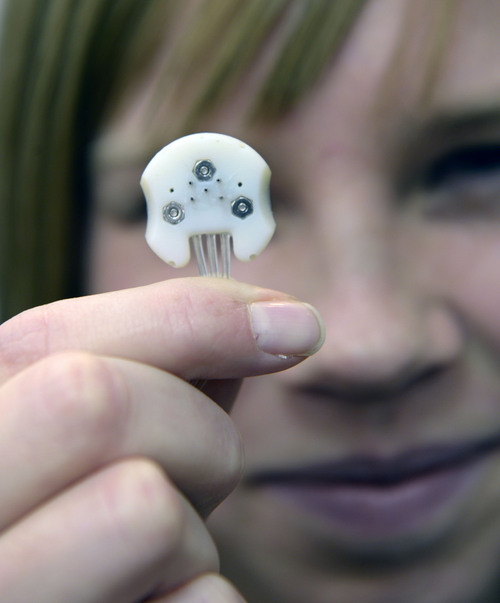

The trio's post-industrial leech consists of a series of small leg-like hypodermic needles on a body 1 inch in diameter (though it could be developed in variable sizes). Really, it's more of a tick than a leech. Exterior needles suck out the fluid while an interior needle applies anti-coagulants — as a leech does through its saliva — to thin the blood and prevent clotting.

The idea came from Jay Agarwal, associate professor in the Department of Surgery and Division of Plastic Surgery and adviser for the project, who pitched it to Bruce Gale, the group's faculty mentor and professor of mechanical engineering.

Agarwal lauds leeches, but at $30 a pop and with many needed for a dayslong course of treatment, they can be pricey. (Team leader Thompson estimates 10,000 treatments a year in the United States, making leeching a $12 million industry.) They also often have to be shipped in because many hospitals don't maintain a live supply. That means doctors can't use leeches for emergency surgeries, such as digit reattachment. And, again, leeches are plain gross.

"Sometimes we'll see these little guys squirming across the floor," Agarwal says.

The U. students' leeches will cost about $200 each, and they think it does a pretty good imitation of their muse.

At first, they thought about creating a leech-style jaw attachment, but "there's a very real chance that that's going to do more damage than good," Ho said, so they opted to tape the bugs on and use sutures. Agarwal says plugging one into damaged tissue would be about as painful as a TB test.

Then, the students — assisted by Gale and Shad Roundy, assistant professor in mechanical engineering — pumped cow's blood through it to make sure it wouldn't clog and tested the device on an orange. It did as expected, though it should be noted that it's an extremely slow way to make orange juice.

Thompson said it was a unique challenge to try to beat a living creature at what it's evolutionarily designed to do.

"And obviously there are still some things that it will still work for," he said. "It's meant to feed."

The group won a bronze medal and $7,500 this month in the undergraduate category at the Collegiate Inventors Competition. They also received a $10,000 award in April as the runner-up at the Bench to Bedside competition.

The next step is to find funding for animal testing, and if it's successful, to submit it to the Food and Drug Association for approval.

Theirs is not the first mechanical leech, however. Scientists at the University of Virginia and the University of Wisconsin at Madison created their own more than a decade ago. But Kuhlman says their devices were simply overthought. (Leaders of both products did not immediately return requests for comment.)

"A lot of those devices completely overcomplicate the blood-removal process," she says. "They're using pumps that are internal to the device … damaging the skin."

Plus, the U. students' device can be used with exterior pumps that are readily available, adjustable and reusable, saving costs.

Agarwal shares the group's high hopes for the critter.

"Other technologies have not been able to really recapitulate what a traditional leech would do."

Twitter: @matthew_piper