This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Midvale • Tranquility. That's the feeling on a weekday afternoon at The Road Home's Midvale family shelter.

Kids are playing. Some parents lounge in the shade outside.

There are no drug dealers. No crazed-looking people. No cars cruising by.

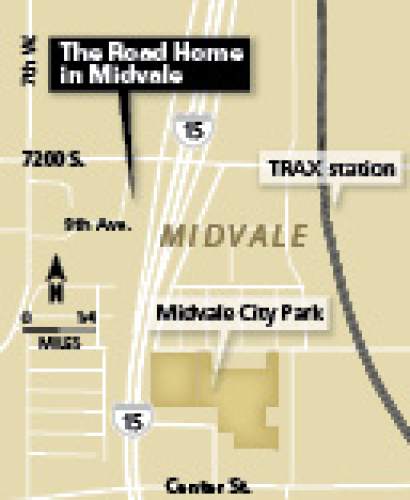

The 2,300-square-foot family shelter, 529 W. Ninth Ave., has a maximum occupancy of 300, about a third the average nightly population of The Road Home shelter on Rio Grande Street in downtown Salt Lake City.

Virgina Blankenship likes it. "We don't have all the people outside," she says, comparing the new shelter to downtown. "My husband calls them zombies. My kids have seen things down there they shouldn't have seen in a lifetime."

The couple have five children, and everyone in the family bunks together — as is the norm at the Midvale facility. The second floor of the shelter is like a big bunkhouse. It has restrooms and also is equipped with a small space for weekly visits from Fourth Street Clinic health care providers.

Downstairs has a children's playroom, restrooms, laundry facilities, a pantry and kitchenettes, where clients cook their own meals.

The building also has a large patio on the roof with 24-hour access for clients.

Transportation can be something of a challenge, however, because the family shelter is in an industrial area. The TRAX light-rail line is three-quarters of a mile away. The bus stop is half as far.

Blankenship's husband is a construction worker but has not found work. "People don't want to hire him because we're from the shelter," she says.

In 1998, The Road Home began leasing an old warehouse on the site as a winter overflow shelter. In 2012, the organization bought the building and planned to renovate it, but then determined to build a new facility on the grounds. It opened in November as a year-round shelter for families.

The land cost $1.2 million. Construction came in at $5.5 million.

Of course, no homeless shelter is without noise and disagreements. There are arguments and even fights, but a 24-7 staff presence keeps things under control and a Unified Police Department officer is assigned for quick response, says shelter manager Melissa Meyer.

Single dad Jason McCowen is staying at the shelter with his children, Daniel, 5, and Dakota, 3. He also has custody of Lydia Trujillo, 8.

After the breakup with the mother of his children, McCowen says it has been a challenge to hold down a job while taking care of the kids. He hopes soon to be back on his feet.

McCowen, who has never before been homeless, says that when he heard about the Midvale shelter, he asked for help.

"It took 45 minutes with paperwork and we were in and they fed us," he explains.

"This is a safe place and they do help out a lot. Since we've been here, it's allowed the kids to be kids. It's not so stressful," he says. "Coming here, you get some drama. But that's going to happen."

Although Utah has almost eliminated narrowly defined "chronic" homelessness — when people are homeless for more than a year or for several times over three years — an estimated 14,000 homeless people remain here, according to the federally mandated "Point In Time" count from January.

The Salt Lake City mayor's task force on homelessness is seeking to build two new shelters that would house 300 people each. The group, however, has yet to create designs or find locations for the facilities.

Working with Salt Lake County's Collective Impact program, city officials and others persuaded the 2016 Utah Legislature to fund $9.2 million for new shelters and services. City and county officials hope lawmakers will make similar allocations in 2017 and 2018.

Part of the reason for new shelters is to reduce the population of homeless people in downtown's Rio Grande neighborhood. Despite the recent opening of the Midvale shelter, that has not happened, says Matt Minkevitch, executive director of The Road Home.

"Downtown, a greater number of people are staying with us on a nightly basis. And steadily, more people are staying outside [near the shelter]," he says. "Those kinds of factors affect a neighborhood."

Christa Jessup, her fiancé and two children are staying at the Midvale shelter after they lost their Taylorsville home.

She says she doesn't like the environment around the shelter on Rio Grande Street.

"I'm afraid of downtown," she says. "Somebody came up to my car and asked if I wanted to buy drugs."

Although her fiancé has a car and a job, it's difficult to find a house or apartment to rent, she says, because of their homeless status. "It's proven to be quite tough," she says. "Who wants to rent to someone like us?"

The Road Home is helping, she says, by providing leads on rentals. The organization also paid off her utility bills at her previous residence.

The scale of the Midvale shelter makes it easier for staff and providers to match clients with services. Nonetheless, shelters are a stopgap measure.

In the end, Minkevitch says, Americans need to ask themselves why there are so many homeless people.