This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

St. George • Nearly 160 years after the massacre of a wagon train in southern Utah, the pioneers' descendants got their first glimpse of what is believed to be their gravesites.

Descendants of the Mountain Meadows Massacre victims gathered Saturday about 35 miles southwest of Cedar City to look at piles of rocks. Those rocks could likely be where their relatives were laid to rest, according to a California archaeologist.

In August 2014, Everett Bassett found what appeared to be two gravesites on a rancher's land.

Bassett was back there again to lead the descendants, some of whom came from across the country, around the sites. The rocks piled in both places have lichen that is around 120 years old, Bassett said. They also look like they were built in a way that members of the military would have done.

"This is exactly what you would expect if an Army lieutenant told them what to do, but then they sent two different work groups to do it," Bassett told The Spectrum of St. George.

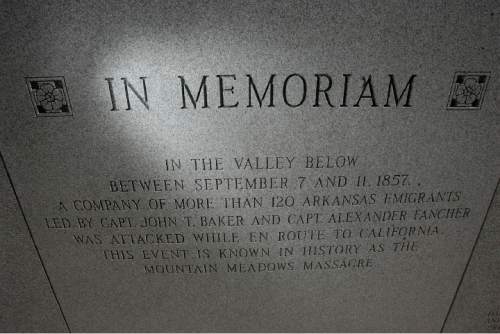

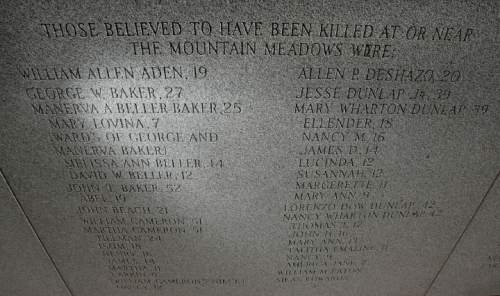

The Baker-Fancher wagon train from Arkansas was heading to California when it stopped in the meadows on Sept. 11, 1857. That is when a Mormon militia shot and killed 120 men, women and children.

In an article about the massacre on The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' website, a historian says the wagon train was attacked during a period of high tensions between the U.S. government and Mormon settlers. The article denounces the massacre as a "terrible episode."

Seventeen young children survived and were taken into Mormon homes. The children were later returned to relatives in the Southeast.

The site was dedicated as a national historic landmark in 2011.

Shannon Novak, a professor at Syracuse University, studied the bones of the victims that were discovered in 1999. She said it may be hard to prove Bassett's conclusions, but he has made a solid argument for the sites being the actual graves.

"There's so much still to learn," Novak said. "That's what it really teaches us is that history is never finished, especially this case, it keeps unfolding."

Several of the descendants said even knowing there are possible graves brings some closure. Scott Francher, who is related to at least 23 of the victims, said he would like the two potential gravesites to also be designated as national landmarks.

"The massacre itself was one of the most sort of important footnotes of our contribution to America's westward expansion," Fancher said. "And this is an incredibly significant historical event, and so as a descendant, I'm proud of the progress we've made."