This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A new-generation exoskeleton made in Salt Lake City's Research Park from high-strength aluminum and some steel allows its wearer to lift significantly more weight than a prototype rolled out two years ago, enhancing its potential for military and industrial applications.

Developed by Raytheon-Sarcos, a unit of Massachusetts-based defense systems contractor Raytheon Co., the upgraded suit, named XOS-2, makes objects lifted by the wearer 17 times lighter. It uses 50 percent less energy and, at 195 pounds, is 10 percent lighter than its predecessor.

Test engineer Rex Jameson easily handled dozens of repetitions lifting a 200-pound weight during an XOS-2 demonstration Thursday. He handled a 50-pound model of an artillery shell like it was nearly weightless and punched his way through four 1-inch boards bound together.

Following the demo with the model shell, mechanical engineer Marques Rasmussen struggled to move the shell a short distance. Rasmussen then tried the 200-pound weight and worked hard to complete two or three reps.

Exoskeleton developers felt the next-generation suit was ready to roll out for public scrutiny and timed its debut to coincide with Paramount Pictures' release this week of the Blu-Ray/DVD versions of "Ironman 2." Movie officials, familiar with Raytheon-Sarcos' early work and hoping to generate publicity for their home-video release, were on hand for the demonstration. They believe the suit is the closest in the real world to the movie version of the Ironman costume.

"The timing was perfect" for marrying the two interests, said Raytheon spokeswoman Corinne Kovalsky.

The exoskeleton is designed for a variety of uses. It can be used to allow a wearer to move heavy plates of metal in a shipyard and hold those plates in place as they are being welded.

Rather than using machinery to pick up, haul and place materials, having the human element involved can make work more precise and cut down on time to bring in cranes or other devices, said Fraser Smith, Raytheon-Sarcos vice president of operations.

Or the computerized suit can be worn, say, by Air Force and Navy aviation workers to load bombs onto the undercarriage of aircraft or place munitions into storage or onto trucks for shipment. The full exoskeleton gives a worker the strength to pick up in each hand and handle, all day long with little fatigue, 50-pound munitions.

Wearing the suit makes the 50-pound weight feel like three pounds, said Jameson, during a break in his vigorous demonstration. Raising the 200-pound weight felt like 12 pounds, he said.

The ratio between actual weight and perceived weight for XOS-1 was 6 to 1. With XOS-2, it is 17 to 1.

"What is nice for me [in lifting all these weights] is, I don't feel it in my back," said Jameson, who has logged more hours in the various exoskeletons than anyone else over the past few years.

When donned, the suit seems to support itself, making its weight barely perceptible. It feels relatively lightweight, similar to a winter coat being draped across shoulders.

The U.S. Government, through the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, funded work on XOS-1 at the rate of $4 million to $8 million a year during eight years. Despite high interest in the project, especially by the military, government funding on XOS-2 has not yet been approved, Smith said.

To that end, Raytheon has dug deep into its internal research and development funds to keep work moving.

"Raytheon is committed to it as a technology that has a lot of promise," Smith said, adding that it can use the exoskeleton in its own manufacturing operations that include communications systems, massive radar installations and a variety of defense projects worldwide.

Once the exoskeleton starts being used in the real world, he pointed out, other buyers, including the military, will see its value in a variety of applications.

For example, Marines on patrol can wear the combat version below the waist that allows individuals to carry much heavier weights over longer distances for long periods. Right now, Marines and soldiers on combat missions carry packs that can weigh 120 to 150 pounds.

But before the exoskeleton is ready for actual use, Raytheon-Sarcos developers need to cut power consumption by another 30 percent. And the current models are tethered to their separate power supply that uses a hydraulic fluid. When warmed and under pressure, the fluid allows the exoskeleton to "take over" the weight of the various tasks while being guided by the human wearer.

"Whatever the human wants to do, the XOS makes him stronger," Smith said.

"Some jobs allow for the tethering," he said. "Say workers are storing or loading munitions in a small area. They can be hooked up to the power source."

But for combat and other environments where mobility is an issue, a small-enough, fuel-carrying backpack capable of operating the suit for up to eight hours is under development.

At minimum, Smith said, it would take Raytheon three years to gear up production of suits for nonmilitary use, such as in shipyards and manufacturing. But it would likely take five years to go through testing for combat applications.

"The military is definitely interested," Smith said. "The real issue is, which one will step forward first and give a set of requirements for us to build a targeted version." The Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps: "They all want different things."

About Raytheon-Sarcos

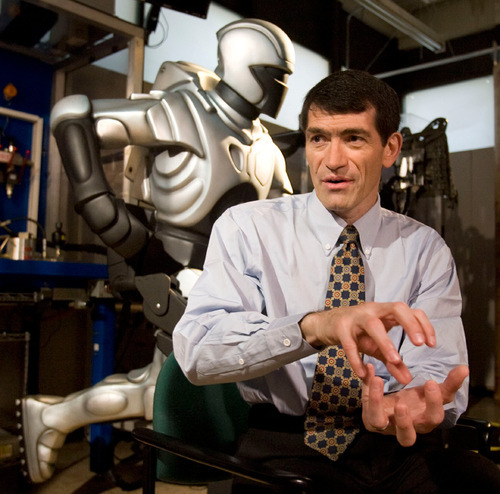

University of Utah engineering professor Stephen C. Jacobsen formed Sarcos in 1983.

The company evolved, in 1987, into Sarcos Research Corp. and focused on creating and commercializing projects developed through the U.'s Center for Engineering Design that Jacobsen had founded in 1973.

Sarcos over the years and in its various iterations has been involved in developing robots for a variety of uses, ranging from entertainment to military. In addition, its engineers and designers have worked on medical systems, such as prosthetic limbs, wearable artificial kidneys and microcameras and catheters, plus a variety of systems such as sensors, sensor networks and power systems.

Defense contractor Raytheon acquired Sarcos in 2007 to put into production exoskeletons, robotic snakes known as unmanned ground vehicles and a plethora of other Sarcos-generated projects. Various medical applications were spun off into a separate company, Sterling Investments LC, headed by Jacobsen as president and CEO.