This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Shanghai • As Asia's financial center, Shanghai has lured many a Utah business eager to cut a company-expanding deal.

The Chinese trading port emerged 175 years ago as the locus of British trade concessions to feed voracious demand for tea, silk and opium, with the French and Americans swiftly following.

Among the world's largest cities with nearly 24 million people and gateway to the globe's behemoth Communist regime, Shanghai is known for its iconic row of skyscrapers standing across the Huangpu River from the colonial Bund, a monument to China's explosive growth.

As with the country as a whole, taking in the symbolism of that skyline can be a bit overwhelming. Salt Lake City real estate executive Lew Cramer said one glimpse redefined his vision of scope and scale.

"You look at the Bund and you see what it used to be," the president and CEO of CBC Advisors said, "and then you look across the river and it might as well be the 23rd century."

The so-called Citrus Summit, held April 6 and 7 at President Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago with Chinese President Xi Jinping, has already sparked upheaval on key trade policies, including a lifting of bans on U.S. beef imports. Trump has also declared China would not be labeled a currency manipulator in an upcoming U.S. Treasury report, partly because the U.S. dollar is now strong.

Derek B. Miller, president and CEO of World Trade Center Utah, noting China's status as a key Utah trade partner, praised efforts to bring down barriers. "Utah businesses, particularly those in the food and agriculture industry, will benefit as the U.S. ensures free trade with China is also fair trade."

—

Ground zero

Yet for U.S. businesses with a beachhead in the People's Republic of China and those tenuously reaching across Pacific shores toward new markets, the Trump-era unpredictability only adds chop to already treacherous waters.

The Salt Lake Tribune was part of a 10-day tour of China by American journalists in late February, sponsored, organized and paid for by the nonprofit Hong Kong-based China-United States Exchange Foundation.

Based on Tribune interviews in Beijing, Shanghai and Zhengzhou in Henan province, some 40 years into an experiment with guided free markets, the tectonic plates of China's economy and society continue to shift. Key issues such as fair competition, intellectual property, pollution and labor supplies show signs of improving, government and business leaders said. But from a Western capitalist view, slippery footing is standard.

U.S. companies operating in China report intensifying competition from Chinese rivals in recent years as among their worst problems, according to the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, which has about 3,500 members from nearly 1,600 firms.

Two-thirds of member companies cite corruption and fraud as significant challenges. Fully 70 percent complained about unequal regulatory treatment compared to Chinese-owned competitors, with retail and service companies most likely to report such hassles.

Doing business in China is difficult, and for some major U.S. companies like Google, the obstacles are all but insurmountable.

—

High-tech ambitions

Search engine and web-services company Baidu is known as China's Google, partly because Google and all of its web domains are banned by the authorities.

So are Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and Instagram in a host of internet strictures imposed by the party under Xi. The elaborate system of site blocking and censorship is sometimes called the Great Firewall of China.

Largely shielded from a major world competitor, Baidu dominates China's search market and has grown into one of the largest web companies in the world, with yearly revenues approaching $10 billion. Its corporate campus in Beijing's Haidian District has the same gleaming, playful high-tech atmosphere you might find at Adobe's Utah operations in Lehi or at Baidu's own sister offices in Silicon Valley.

Interviews with Baidu scientists in late February revealed major efforts to develop new technologies in artificial intelligence, facial recognition, robotics, augmented reality and high-performance computing. The company also has a variety of data-sharing arrangements with government authorities, its scientists said.

Notably, Baidu researchers have developed what one called "highly accurate" facial-recognition algorithms capable of matching incoming scans with vast record troves in China's national citizen-identification database.

Baidu said it plans to deploy a test system at the entry gates of more than 100 popular Chinese tourist sites later this year.

—

Hello world

It might be hard to imagine a worker shortage with nearly 1.35 billion people, but with an aging population and rising affluence, China's longstanding edge on inexpensive labor costs is starting to slip.

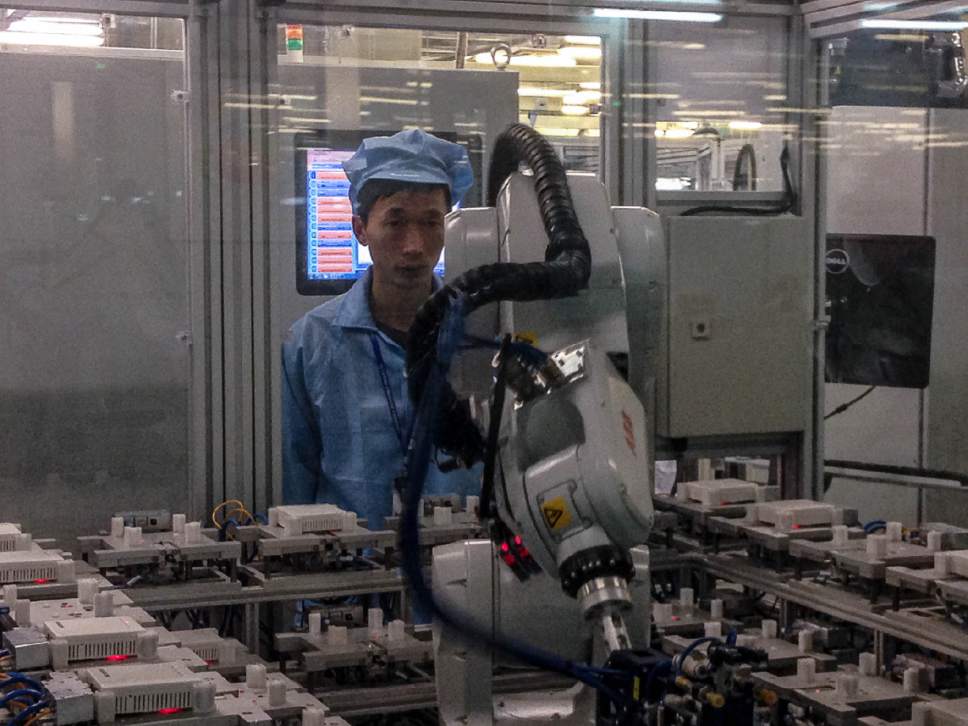

Cue the robots.

Shanghai-based Cambridge Industries, CIG, for short, uses automation heavily along its various production lines of routers, smart-home devices and cellphone components. And the 12-year-old firm expects to replace nearly two-thirds of its 3,000 employees with robots by the end of 2017.

"China is no longer a cheap way for manufacturers," said Gerald Wong, CIG's co-founder and CEO.

On an early March afternoon, angular mechanical arms at successive stations lurched back and forth precisely as they placed pieces of circuitry into CIG's assembly lines, often with one or two humans looking on. Nearby, classrooms full of trainees in lab coats, shower caps and booties attentively watched factory instructors and took notes. Slogans on red banners with bright yellow characters hung on the factory walls with messages about safety, quality and commitment.

Automation has displaced thousands of U.S. workers, particularly in manufacturing, but that's capitalism. Replacing people with machines in China, on the other hand, would seem to run counter to its national socialist vision.

Yet China's rulers have committing billions of yuan to a five-year technological upgrade of the country's manufacturing sector, which employs upwards of 80 million people.

When a deputy Shanghai mayor recently visited the CIG factory, Wong said, "he was pushing us to go faster."

Demographics are driving the trend.

China's one-child policy — launched as a population-control measure in 1979 and phased out starting in 2015 — has left immense gaps in the country's age mix and a graying, shrinking and increasingly choosy workforce. As average incomes rise, Wong said, many are often passing over factory work.

—

Earth movers

Out on China's dusty east-central plain, an otherwise unremarkable state-owned enterprise in a city called Zhengzhou gives a telling illustration of steady and near-unfathomable momentum.

Like so many enterprises run by China's one-party regime, its name is bland and direct: China Railway Engineering Equipment Group Inc. (CREG).

Yet the massive industrial machines CREG makes in its 11 factories drill some of the largest tunnels on the planet. Its boulder-chewing monsters — up to 55 feet in diameter — are capable of boring about a third of a mile a month through solid rock, while being operated by about a dozen workers at a time.

As rotating cutters break and grind rock, a sophisticated slurry system conveys debris backward for removal. The tunnel-boring machines, or TBMs, simultaneously lay tunnel support walls as they burrow forward.

This is earth-moving on a global scale.

CREG has produced more than 700 of these TBMs, with 400 now in operation, pretty much steadily, on project sites across 30 Chinese cities. At up to $14.5 million per unit, they are drilling railroad and freeway passages, reservoirs, underground parking lots and warehouses, even urban sewage conduits. They were instrumental in recent pre-Olympic Beijing subway extensions.

"If you want to make a tunnel," CREG lead engineer Ning Haosong said, "we can give you all solutions."

CREG's output has risen sharply in the past four years, Ning said, amid demand among domestic builders and, increasingly, foreign markets such as Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam and Israel. CREG's parent company is now listed on the Fortune 500.

—

Bluer skies?

Some of these same large state-owned enterprises are also the country's heaviest polluters, part of what environmentalist Ma Jun argues has been a long-term and devastating outsourcing of the world's environmental costs to China.

Air, water and soil pollution pose an ongoing threat to public health and social stability, driven by the nation's rapid growth into a world center of industrial production for low-cost goods, said Ma, the director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs in Beijing.

"Despite putting so many resources into solving these problems," said Ma, "we still hadn't seen a turning point."

Years of smog churned from factories and China's growing number of automobiles gave way to widespread protests in 2011, sparked by a particularly choking spate of inversions in Beijing. The government took grave notice, Ma said, and responded with an unexpected tool: transparency.

Records on public pollution citations and data from thousands of air- and water-quality sensors across 338 municipalities have since been made public, and through his small, nonprofit institute, they are now online and available in real time, Ma said.

Public participation now appears to be improving conditions in some cases, he said. "The feeling now is our way — based on data, based on science — is better than street protests."

Supporting this monitoring grid is a micro-reporting and petitioning system allowing citizens to officially complain about polluters, creating public opportunities to "shame" companies and government officials who do not respond. That crowdsourcing, Ma said, is part of a wider, emerging accountability reminiscent of Western democracies.

Communist Party officials are now being evaluated on their handling of pollution crises in their districts as they are vetted for party advancement, Ma and others said.

Civic pressure has also led many state-owned enterprises and major Western-based manufacturers with operations in China to begin cleaning up their supply chains.

"They are now under such pressure to really try to solve environmental problems," Ma said in late February. "Now there is some real political will, because smog is really big on the minds of the public, including their leaders."

Ma said he also was heartened by U.S.-China trade discussions and the prospect of shifting manufacturing employment back to America.

"You need new jobs," Ma said, "and we need blue skies."

—

Editor's note • Tribune editor and former business reporter Tony Semerad traveled to China in late February with U.S. journalists touring Beijing, Shanghai and several cities in east-central Henan province. Meant to promote understanding between the two countries, the 10-day trip was sponsored, organized and paid for by the China-United States Exchange Foundation, a Hong Kong-based nonprofit, nongovernmental and privately funded group.