This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The University of Utah boasts it has spun off more than 100 companies in the past six years, based on ideas developed on campus. While the school touts its status as No. 1 among research institutions for starting companies, some appear to be companies in name only.

The U. has launched 35 companies as wholly owned entities of the university since 2007, 20 of which it lists as startups. Many have no office, payroll, permanent leadership or assets. In state filings, most list as their address the suite at 615 Arapeen Dr., where the U.'s Technology Commercialization Office (TCO) operates in Research Park.

TCO chief Brian Cummings is a registered agent or officer of at least 32 companies, according to incorporation records kept by the Utah Department of Commerce. By setting up corporate shells owned by the U., officials say they can pursue federal grants and venture capital during the early phase of an invention's development and speed it to market. Critics say this novel approach, taken by few other schools, raises the potential for conflicts of interest and antagonizes independent entrepreneurs.

"If the TCO can provide assistance in finding a supportive management team to lead a startup company into a thriving commercial entity, then the program should be considered a success," said Sheryl Hohle, a one-time TCO licensing manager who quit a few years ago. "However, if the TCO approaches the inventor rather than the other way around, if the inventor isn't a founder in the company, if the management team is composed of university employees who clearly don't have time to run a startup company, and if there is no technology license and no payroll, then is it really a startup company?"

Hohle is concerned that the U.'s model, which "cherry picks" technologies to sell as companies rather than just licensing technologies, could undermine tech transfer by "creating higher price tags for Utah's local entrepreneurs" to participate.

Since 2005, the U. has aggressively pushed technology into the marketplace, using graduate students to develop business plans, help faculty turn inventions into products and in many cases, establishing the businesses and pursuing grants. The process is shrouded in secrecy because of confidentiality agreements, yet the TCO operates outside of a policy framework and with limited faculty oversight.

Meanwhile, some entrepreneurs who want to license technology complain that the TCO is slow to propose terms, costing them precious time and sweat. When the terms finally come, entrepreneurs say, the terms won't sustain a successful business.

Suzanne Winters, the state's former science officer who now leads USTAR's BioInnovations Gateway, said the TCO could do a better job.

"If the University of Utah has economic development as part of its mission, they have an obligation to structure the terms of the licenses to enable those companies to succeed, to get the licenses out in a timely manner and the terms are standard within the industry," she said.

University officials deny they demand untenable deals, claiming their intent is to help licensing partners, not make the university rich.

Duane Ruffner, founder and CEO of Symbion Discovery and Sheryl Hohle's partner, is investigating how to synthesize potentially therapeutic compounds based on technology developed by a U. chemist. The firm hopes to produce molecules that occur naturally in bacteria found in sea squirts and other tiny ocean creatures, then test them for anti-cancer properties.

But after three years of negotiating with the TCO, Ruffner has yet to secure a licensing agreement. TCO officials initially urged him to cede ownership of his company to the University of Utah Research Foundation (UURF), the nonprofit that owns the U.'s intellectual property.

"There's nothing attractive about all this. You're asking me to do all this research, create this value only to be forced to buy it," Ruffner said. "The terms kept changing. You think you have an agreement, and the next thing you know the terms get more onerous."

But TCO Associate Director Zach Miles said Ruffner and Hohle gummed up negotiations by seeking terms unfair to the university.

Ruffner's experience illustrates the contentious underbelly of the university's innovative approach to transferring technology to the private sector. While the system is credited with driving a boom in business startups, some entrepreneurs believe it stacks the deck against independent operators. Only Ruffner would speak on the record; others said they didn't want to jeopardize ongoing negotiations.

—

The TCO innovation • U. administrators say there are sound reasons for starting businesses under UURF control with Cummings and other officials as stand-in principals. This expedites grant acquisition, which helps advance the technology, and potentially attracts investors, according to Jack Brittain, vice president for technology ventures and the architect of the U.'s tech-transfer system. When venture capital and grants arrive, the U. officials resign their roles in the companies.

Said U. general counsel John Morris: "We provide a bridge, a vehicle where the early work can be done while it's still owned by the university, so it's more likely to get the SBIRs [Small Business Innovation Research grants] or other outside funding. We may retain up to 49 percent interest, but that is in the nature of a passive investment."

When they incorporate the companies, officials file papers with the state Department of Commerce outlining stock-issuing arrangements so that the university's stake is watered down as investors buy in. According to data provided by the university, eight of the 35 UURF companies have been transferred to outside management and three have dissolved.

Proponents say this arrangement allows entrepreneurial faculty to shift commercialization risks to the university and to keep up their research.

Short Solutions, started by four electrical engineering students last year, is one UURF success story. For their senior project, the students explored a technology developed by professor Cynthia Furse for diagnosing electrical faults in aviation systems. The team adapted Furse's patented inventions for use in automobiles, then received invaluable help from the U.'s Lassonde Entrepreneur Center to develop a prototype called SmartFuse, set up a UURF-owned business and secured grants totalling $85,000, according to Furse.

Management of Short Solutions has been handed to the students, but Cummings and Brittain are still listed as officers of the company.

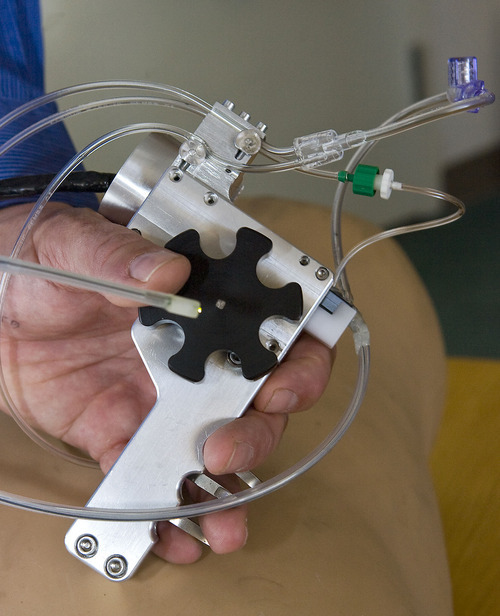

And some new startups not owned by UURF are reeling in venture capital, creating prototype products that could make a big splash, particularly in the medical device arena. Catheter Connections recently released a medical device that is expected to substantially cut IV-related infections in hospital settings. Veritract, started by U. gastroenterologist John Fang, is developing a safer feeding tube. Another firm markets a device that rids people of head lice by blowing warm air through their hair, while another uses ozone microbubbles to neutralize industrial pollution.

"We are not in this for money. We are in it so the inventions of our faculty are available to public. We want to make deals that are going to fertilize the research process," said Morris.

—

Valued employee • Excluding the UURF companies, the U. has spun off about 90 firms since Brittain hired Cummings in 2005 to run the TCO and its 10 employees.

According to annual rankings issued by the Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM), the U.'s closest competitor in startups is MIT, which has a research enterprise four times larger.

Cummings' $249,000 base salary could be an indication of how much the university values his talents. It exceeds the median for chief technology transfer officers by $89,000, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education's survey of administrative salaries. Although he does not hold a doctorate, Cummings earns more than the deans of the U. colleges of Social and Behavioral Science, of Mines and Earth Sciences, and of Science.

Last month, Ohio State University, whose research enterprise dwarfs the U.'s but which lags in commercialization, hired Cummings and will pay him $365,000. He starts the new job in June.

Cummings did not respond to phone and email requests for an interview.

Under the direction of U. President Michael Young, technology commercialization was moved out of the research division into a new unit led by Brittain. The former business dean restructured what was then called the Technology Transfer Office to speed commercialization of intellectual property, help faculty inventors become entrepreneurs and be active partners in the early phases of development.

The changes were also intended to maximize the possibility of commercial success, according to Brittain. The new approach has won kudos from the U.'s leading faculty entrepreneurs, such as Glenn Prestwich and Furse, and outside observers like AUTM.

"The real mission of the university is education and the development of new ideas. This is exactly a marriage of these two," said Furse, an electrical engineer who serves as the U.'s associate vice president for research.

But the U.'s tech-transfer overhaul has meant abandoning some key National Academy of Sciences guidelines: At the U., tech transfer is no longer run by the research division, and the faculty oversight committee is inactive. When it did meet, its task was to vet invention disclosures, not provide the oversight called for under university policies.

"Universities are really slow and deliberate," Morris said. Tech transfer "is an area that requires quick action."

The U.'s published policies have yet to be updated to reflect current practices. Morris said those policy revisions are pending.

Tom Parks, vice president for research, said commercialization is a better fit in the tech ventures division, which fosters outside-the-box thinking, than in the research division's "culture of compliance." Park also said that as the president of the UURF board, he is the academic voice in the process, with veto power over every licensing deal.

—

"It could be win-win" • In the 1990s, Ruffner, then a researcher with the U. College of Pharmacy, tasted the promise of technology transfer when he helped launch Salus Therapeutics with Dinesh Patel, Utah's leading venture capitalist. He returned three years ago to give commercialization another go and waded through the U. portfolios of intellectual property.

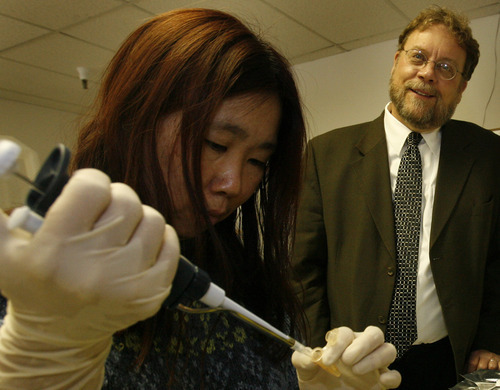

One invention disclosure whetted his appetite: A genetic pathway to synthesize natural compounds that could form the basis of new drugs. The inventor is Eric Schmidt, a young professor of medicinal chemistry. Schmidt discovered these compounds in tiny marine organisms, but those organisms are available only in quantities too small to be of practical value. In a 2006 study, Schmidt described how to synthesize the compounds.

Ruffner spent more than a year trying to get the TCO to provide him "a term sheet," which proposes licensing fees and royalties entrepreneurs pay in exchange for use of a patented invention. But the office lacked confidence in Ruffner's business acumen, according to Moj Eram, the licensing officer negotiating with Ruffner.

"He is a researcher, not a businessperson. We vetted Duane for his expertise and we didn't find him a suitable candidate for running this company," Eram said. "The recommendation [to form a UURF company] was to help him, not put a hurdle in front of him, to get a management team and to get grants."

Ruffner said he was not interested in the TCO's help because it did not appreciate the potential of Schmidt's idea until he pointed it out.

"If you have the skills, why make a company that you would have to buy at an elevated price?" Ruffner said.

In the meantime, he spent a year without pay in Schmidt's lab, then secured two federal SBIR grants worth more than $400,000 and set up Symbion with five employees.

As the negotiations lumbered along, the TCO rejected Schmidt's applications for competitive R&D grants.

TCO lawyer Zach Miles said the grant decisions were made based on recommendations by a third party to avoid any conflict of interest.

Ruffner said he finally agreed to the TCO's terms, only to be confronted with a last-minute "bombshell" last November in the form of "reach through" provisions claiming a stake in new applications he might discover. That provision had never been discussed in months of negotiating.

"These are idiotic terms that are deal killers. We could agree to them but it would make no business sense," Ruffner says. Neither party could divulge their proposed terms because licensing negotiations are subject to confidentiality agreements.

Ruffner believes he has done the university a favor by testing the viability of Schmidt's inventions.

"You would think they would wish to have a collaborative relationship with us," he said. "If we can't have a license, we can't continue to develop it. Who is going to develop it? It could be win-win."

Tech transfer 101: How inventions make it to the market

Under the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, federal policy encourages universities to patent technologies developed as part of federally supported research. Commercializing inventions is believed to hold broad social benefits and spur economic development.

The first step to transfer technology to the private sector requires research faculty to file an invention disclosure with the university. Licensing managers assess the potential of the proposed invention for a patent, which grants the holder an exclusive right to profit from the idea and license that right to others.

If the idea is deemed worthy, university officers apply for a patent and invite entrepreneurs to carry the idea forward as a commercial concept. Traditionally, schools work out a licensing agreement with the entrepreneur, spelling out terms by which the university will be compensated in the form of up-front fees and royalties, typically a percentage of gross revenue. Faculty inventors normally get a 30 percent cut.

Most often, a university licenses a patent to an established company, but sometimes the patent will go to a small business set up specifically to commercialize it. The federal government sets asides millions of dollars to invest in these efforts in the form of Small Business Innovation Research grants.

Under the University of Utah's innovative approach, officials expedite commercialization by developing business plans and market studies, securing grants, forming companies themselves and providing lab and office support.

Utah's famous startups include Myriad Genetics, which has employed up to 800 people, and the robotics firm Sarcos, later acquired by Raytheon. The U. spun off its first startup in 1970 with TerraTek, later acquired by the oil-field services firm Schlumberger and which still operates in Salt Lake City with 80 employees.

A recent report by the Utah Bureau of Economic and Business Research says U. spinoffs now account for nearly 6,000 jobs in Utah and help generate $1.2 billion in economic activity. —

U. tech commercialization in 2009

79 • Licenses executed

246 • Active licenses

$12.4 million • Licensing revenue

19 • Startup companies launched

60 • Jobs created

200 • Invention disclosures filed

108 • Patent applications filed

35 • Patents issued

$11.1 million • Private financing raised

$3.1 million • Grants awarded

Source • Association of University Technology Managers, University of Utah This nonprofit owns the university's intellectual property arising from research, much of it publicly funded. Its assets include more than 5,000 invention disclosures and 1,661 patents, which are managed by the university's Technology Commercialization Office (TCO). The office lists 369 technologies currently available for licensing and raises more than $12 million a year in licensing fees and royalties. About one-third of that goes to faculty inventors.

The UURF is run by a board of high-level U. administrators and two outsiders. Current board members are President Michael Young, who acts as chairman; Tom Parks, vice president for research; Jack Brittain, vice president for technology ventures; general counsel John Morris; David Pershing, senior vice president for academic affairs; Lorris Betz, senior vice president for health sciences; Arnold Combe, vice president for administrative services; Roger Boyer, a university trustee and real estate developer; and entrepreneur Jim Jensen. Its board helps oversees the TCO.

The foundation cycles some revenues back into the technology commercialization process. This revenue underwrites grants geared toward catapulting fledgling firms across "the Valley of Death" that separates the lab and the marketplace.

The TCO also has steered nearly $1 million in federal stimulus money to projects associated with U. technologies. Each year, the UURF spends about $5 million on administrative expenses, including patent costs and legal fees, according to IRS filings.

– Brian Maffly