This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It has been more than three years since Tony Velasquez got the news no one wants to hear. He is dying. It's just a matter of time.

And yet on this day in March 2010, he tells his friend, hospice chaplain Peter Nackowski, a story that is all about life.

Velasquez's 4-year-old grandson, Corbin, had been watching him whip up pancakes over the weekend and suggested another ingredient.

"Stir in some love," Corbin told his grandpa.

"That was a moment, wasn't it?" asks Nackowski.

"It was," says Velasquez. "It was."

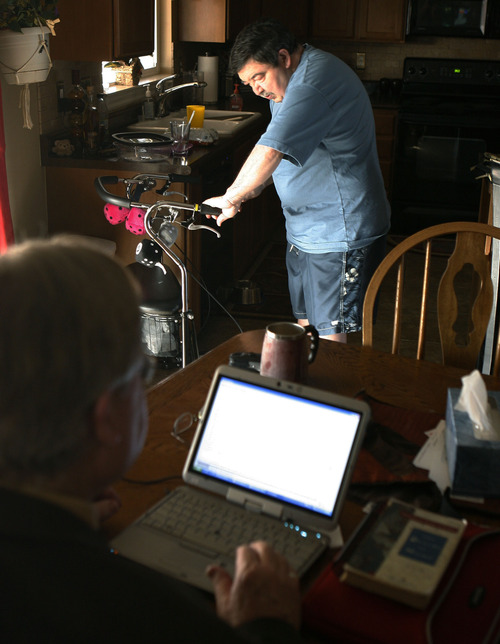

Once a week for an hour or so, Nackowski visits Tony Velasquez at the Syracuse home he shares with his wife, Robin Velasquez, a house that increasingly is Tony's world.

Tony no longer rides a four-wheeler in the Uinta Mountains nor "invites the fish for breakfast" with a graphite rod — pastimes that once reminded him of the beloved peaks surrounding his hometown of Ignacio, Colo.

Although Tony feels closest to God in "the chapel of the whispering pines," he rebuffs many of his wife's attempts to take him for a drive for fear that it will only remind him of everything he no longer can do in the outdoors.

"What it does is take the disease and stick it in my face," Tony says one day in early summer. "Sometimes, I don't like where I'm at."

It's Nackowski's job to help Tony with perspective, to help him tap into his spiritual reservoir.

"The most enlightening thing for me with people facing an indefinite prognosis," Nackowski says, "is the courage they build over time — and the joy when they're able to experience [dying] free of fear."

—

Trouble in paradise • It was 2006 when the Velasquezes first noticed something odd about his gait. Tremors, too, showed up while they were visiting friends in Hawaii that year.

The Aloha State held good memories for the couple, who met on a Navy ship in North Carolina and married in 1992 after each of their prior marriages failed. Each of them has two daughters.

Tony, just retired from the Navy, earned a bachelor's degree in applied engineering at the University of Hawaii when the Navy transferred Robin to Hawaii.

After Tony's mother died in 1996, the couple wanted to be closer to his family in Colorado, so they moved to Washington state and then to Utah, where she worked for the Navy at the University of Utah.

Robin retired in 2002 and went to work at Hill Air Force Base. Tony soon landed a civilian job there as well, teaching aircraft repair to younger men and women, a position he described as the best job ever.

After the tremors began, Tony went to a series of neurologists.

He was diagnosed shortly after his 53rd birthday with atypical aggressive multiple-symptom failure Parkinsonism, a degenerative ailment similar to Lou Gehrig's disease.

Tony kept working, but suffered bad headaches, his memory and balance were off and he no longer could speak clearly. His job required a mastery of repair manuals for four aircraft, and he found them all confusing. "I knew it was time."

In 2008, Tony took medical retirement at age 55.

—

A shrinking world • It's an unusual thing, Robin says one day after a particularly tough time in 2010; her husband has just lost his father and she has lost her sister.

"I know this is an oxymoron, but I feel blessed," says Robin, who, like her husband, was reared Catholic and turns often to the prayers and devotions even though the couple don't regularly attend church.

She thanks God for his timing; she is young and strong enough to care for her husband as he dies a slow death.

Indeed, gratitude seems to grow with Tony's affliction.

One weekend, he has the impulse to put on a Super Bowl party at an Ogden homeless shelter. They buy 300 hot dogs and 15 pounds of baked beans and drop them off at the shelter.

"I have all that I want," he says, "and more than I need."

Death has a way of bringing spiritual matters to the fore.

"It's challenging and we know there's an end," Robin says, "but we're not focusing on the end."

Nackowski's calm way of discussing faith means the world to the couple. He typically reads a Psalm or a passage from the New Testament. On Ash Wednesday, he brings ashes he got from a priest.

"Peter has been here watching as the world is getting smaller," Robin says. "He listens. He never passes judgment."

Tony, already beginning to lose his ability to speak clearly, puts it this way: "I don't think I could survive right now without Peter."

—

Final ride • Tony's time will not come for more than two years, long after a new hospice has taken over his care because Nackowski's hospice, Applegate, could no longer prove Tony's wasn't simply a chronic condition.

"I always saw decline in Tony because I struggled to understand him and it was increasingly difficult," Nackowski says. But chaplains, he says, "don't have the medical background to judge."

Another chaplain takes Nackowski's place for the final months of Tony's life, helping him, along with other hospice workers, have a good death.

"He was surrounded by some very good healers," Robin says.

Tony's daughters, who live back East, visit around Thanksgiving, filling the house with the noise of the couple's grandchildren.

On Dec. 7, Tony's failing health slips markedly. His brother and sister come, and he tells them he sees horses on the ridge, coming for him. Later, he tells his brother that his ride will be an Appaloosa mare.

A hospice nurse mentions there is great energy in the room. Robin believes it is from angels and deceased loved ones ready to escort her husband home, and Nackowski chuckles at Tony's image of horses as heavenly escorts.

"I would have loved to be there for the entire journey."

Editor's note

Tony Velasquez, a Navy veteran and submarine mechanic, died at age 60 on Dec. 11, 2012, more than six years after he was diagnosed with a degenerative disease. The Salt Lake Tribune spent time over several months with Velasquez and his hospice chaplain, Peter Nackowski, to better understand the chaplain-patient relationship. This story provides a snapshot from that period.