This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Horned ceratopsid dinosaurs, the family that includes the familiar triceratops, are famous for their oversized noses, but a specimen recovered in southern Utah's Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument takes this facial proboscis to new lengths.

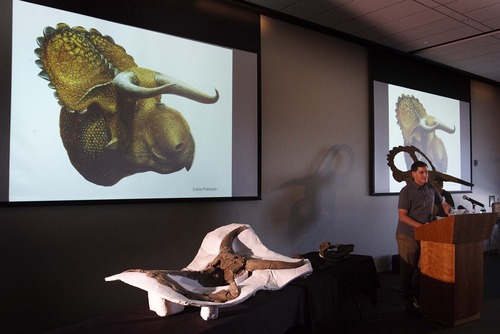

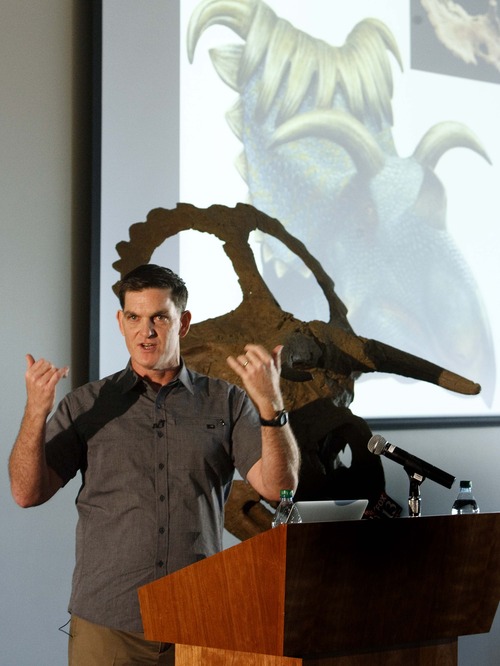

Previously unknown to science, the specimen formally earned a species name Wednesday as the Natural History Museum of Utah unveiled the fossilized remains. The research team led by Scott Sampson — aka Dr. Scott of public television's "Dinosaur Train" — dubbed the creature in honor of the monument's paleontologist, Alan Titus.

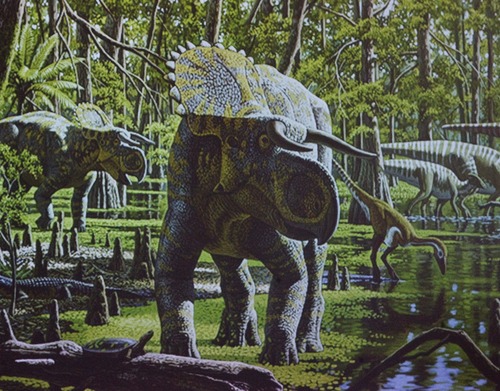

Nasutoceratops titusi was a 15-foot long, 2.5 ton plant-eater that roamed the eastern shore of a land called Laramidia about 76 million years ago, according to University of Utah research published Wednesday in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The genus name is Latin for "big-nose horn face." Its head features massive horns over each eye and a beak-like protrusion beyond its jaws.

"The jumbo-sized schnoz of Nasutoceratops likely had nothing to do with a heightened sense of smell — since olfactory receptors occur further back in the head, adjacent to the brain — and the function of this bizarre feature remains uncertain," said Sampson, who conducted the research when he was a NHMU curator, in a news release. He is now vice president for research and collections at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

A cast of this skull is mounted on the Natural History Museum of Utah's striking wall of ceratopsids at position No. 6.

"The amazing horns of Nasutoceratops were most likely used as visual signals of dominance and, when that wasn't enough, as weapons for combatting rivals," said Mark Loewen, a museum paleontologist and a U. geology professor.

Then-U. graduate student Eric Lund discovered the specimen in 2006 in the pink and gray mudstones of the Kaiparowits Formation, a layer of Late Cretaceous sediments that has yielded as many as 20 dinosaur species new to science in recent years. Loewen hopes to unveil another new specimen this fall.

Lund made his find during a field expedition about 12 miles southeast of Kodachrome State Park. He observed the lower part of a skull protruding from a cliff and a U. team eventually recovered most of the horned skull and a forelimb.

The research team spent a few years assembling the skull. While its facial features were quite distinct, the rear plate, or bony frill, was rather plain as far as ceratopsids go. Its scalloped margin is a far cry from the hooked and spiky ornamentation seen on other specimens mounted in the museum's Past Worlds gallery.

Since Lund's discovery, fragments from two other Nasutoceratops specimens have been found in the Kaiparowits, which was deposited when a shallow seaway separated the eastern and western halves North America. Utah occupied the western portion, a narrow band that stretched from present day Mexico to Alberta, Canada.

Discoveries like Nasutoceratops highlight the astonishing dinosaur diversity that existed on Laramidia — about the size of Australia — in the Late Cretaceous, about 8 million years before a meteor strike put an end to the reign of reptilian megafauna.

Just five giant mammal species live today on Africa, a continent four times the size of Laramidia. But 76 million years ago, there may have been up to two dozen species of large dinosaur on Laramidia. How could so many massive creatures co-exist on such a small landmass?

Loewen suspects the island's north-south orientation meant much different plant communities grew at either end, so big herbivores had to adapt to divergent food sources. He also believes changing sea levels may have periodically separated the north and south, ensuring populations would not be able to interbreed and go down separate evolutionary paths.

The Kaiparowits Plateau is the central portion of the nation's largest national monument. Grand Staircase-Escalante covers some of the most remote terrain in the lower 48 states.

"It really is a gold mine. It's the last undiscovered territory in the U.S.," Loewen said.

Co-authors on the new study are the museum's Loewen and Katherine Clayton, Sampson, Lund (now at Ohio University) and Andrew Farke of the Raymond Alf Museum. It was funded by the BLM and the National Science Foundation.