This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Alfred Hitchcock, who is said to have had a macabre sense of humor, would have appreciated that his work is more critically acclaimed now — a third of a century after his death in 1980 — than during his lifetime.

When he was alive, Hitchcock never won an Oscar, though the motion-picture academy did give him the Irving G. Thalberg Award in 1968. And last year, Sight & Sound magazine's once-a-decade poll of film scholars — considered the most authoritative Top 10 list in the film world — put Hitchcock's 1958 psychological thriller "Vertigo" at the top of the list of best movies ever, knocking off longtime leader "Citizen Kane."

The filmmaker continues to generate such fascination that Hollywood made two movies about him in the past year: "Hitchcock," which starred Anthony Hopkins as the director during the making of "Psycho," and "The Girl" for HBO, in which Toby Jones played Hitch while he made "The Birds."

One would be hard-pressed to name a filmmaker whose work has endured, with critics and audiences, the way Hitchcock's films have.

"With some great directors, you're looking at two or three masterpieces. With him, you're looking at 10 or 12," said filmmaker Sacha Gervasi, who directed the biopic "Hitchcock," in an interview with The Salt Lake Tribune last year.

Salt Lake City moviegoers will get a chance to see the best of "The Master of Suspense" on the big screen with a 15-film monthlong retrospective starting Friday, Aug. 2, at the Broadway Centre Cinemas, 111 E. 300 South, Salt Lake City.

To Tom Sobchack, professor emeritus of film at the University of Utah, Hitchcock is a rarity: a filmmaker who was able to develop a unique signature while working within the confines of the old Hollywood studios.

"The studio system normally is not where you find a distinctive style, film after film after film," Sobchack said.

Hitchcock's style, Sobchack said, was initially influenced by the German expressionists — such as F.W. Murnau. And, like those silent filmmakers, Hitchcock learned to use visual elements to tell his stories in ways dialogue could not.

For example, in "To Catch a Thief" (1955), Hitchcock suggests a sexual encounter between Cary Grant and Grace Kelly by panning away from them kissing to an open window — and the fireworks outside. Or, in "The 39 Steps" (1935), when a woman discovers a dead body in a man's apartment, her scream is replaced by the whistle on the train the man is riding.

Hitchcock "kept that sense of the visual as an important element, particularly when there is something terrible about to happen," Sobchack said.

A viewer can also dig into Hitchcock's films for clues to the director's psychology.

Sobchack recalled the story Hitchcock used to tell about his childhood, when his father sent the then-5-year-old to the local police station — with a note to the officers to lock him in the cell until his father came to get him. Contrast that with the Robert Walker character in "Strangers on a Train" (1951), who wants to see his father murdered.

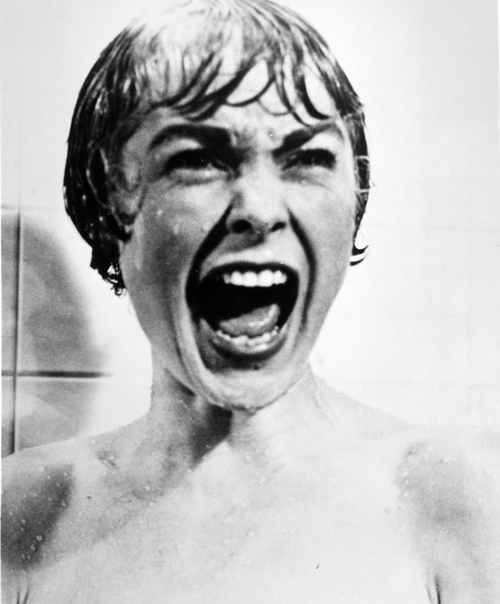

Then there's the issue of the "Hitchcock blonde," the director's habit of casting actresses who were, in Sobchack's description, "blond, slender, cool perhaps rather than hot sexy like Gina Lollobrigida or Maureen O'Hara." The list includes Kelly in "Rear Window" and "Dial M for Murder" (both 1954), Kim Novak in "Vertigo" (1958), Eva Marie Saint in "North by Northwest" (1959), Janet Leigh in "Psycho" (1960) and Tippi Hedren in "The Birds" (1963) and "Marnie" (1964).

Whether the blondes "were representing his fear or desire" is a question movie buffs have been asking for decades, Sobchack said.

Hitchcock was also a model of reinvention.

"What you see when you see 'Rear Window' or 'North by Northwest' is that there's a vast range of movies that he was doing, that were so different to 'Rope' or 'Lifeboat' or 'Saboteur,' " Gervasi said.

Hitchcock could create outlandish scenarios, such as hanging off the Statue of Liberty in "Saboteur" (1942) or climbing the faces of Mount Rushmore in "North by Northwest." He experimented with surrealism in "Spellbound" (1945) and with 3-D in "Dial M for Murder." He made "Rope" (1948) as a one-room chamber piece with no visible edits. He went from the lush color of his '50s masterworks to the brutal black-and-white of "Psycho," giving birth to the "slasher" horror genre.

"People always find a lot in Hitchcock to talk about," Sobchack said. "Something in Hitchcock — and this is almost mysterious — lingers and makes you want to talk about it."

Twitter: @moviecricket

facebook.com/seanpmeans —

Hitchcock at the Broadway

A monthlong, 15-film retrospective of the works of Alfred Hitchcock.

Where • Broadway Centre Cinemas, 111 E. 300 South, Salt Lake City.

When • Friday, Aug. 2, through Thursday, Sept. 5.

Admission • $9.25 for evening shows, $6.25 for matinees.

—

Film schedule:

Aug. 2-8 • "Spellbound," "The 39 Steps," "Shadow of a Doubt."

Aug. 9-15 • "The Lodger," "The Lady Vanishes," "Rear Window."

Aug. 16-22 • "To Catch a Thief," "I Confess," "Strangers on a Train."

Aug. 23-29 • "The Birds," "Psycho," "Rope."

Aug. 30-Sept. 5 • "Vertigo," "North by Northwest," "The Man Who Knew Too Much" (1934 version).

Details • For showtimes, go to saltlakefilmsociety.org