This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

On the night of July 30, 2012, Kaleb Yazzie ironed his shirt and laced up his shoes. He kissed his mother and his sisters goodbye, gave everyone hugs.

He was like that, his family said. Affectionate. A hugger. He never liked to shake hands.

They joked around and teased each other, they said. It was the first time in weeks all five siblings had been together. They couldn't have known that it would be their last.

Yazzie went to a movie with his brother and then a party with friends at a Capitol Hill home, where there were drugs and alcohol and games and girls and a man named Adam Karr.

In a matter of hours, Yazzie's freshly ironed shirt turned to a red-stained rag as it soaked up his blood.

Yazzie, 22, died on the pavement outside the house in the early dark of morning.

Karr had stabbed him seven times in the neck and chest. On Tuesday, he will be sentenced for murder and obstructing justice.

Karr, who was convicted by a jury in June, has insisted he acted in self defense. He claims he was afraid of Yazzie, who had thrown up gang signs and bragged about his ability to fight. He said he was protecting his brother, his home, his friends.

But Yazzie's family said the young man Karr claims to have killed was not the Kaleb Yazzie they knew.

Yazzie was quiet and shy. He was a sensitive kid who avoided conflict and preferred spending time creating art to rough-housing. He talked slow, was careful in choosing his words.

The night before he died, his mother had called out to her sons as they left to see "The Dark Knight Rises."

"Be careful out there," she said. "It would kill me if something happened to either of you."

Yazzie smiled and folded his small mother into his arms.

"Oh, Mom," he said. "Don't be silly."

—

Beginnings • Kaleb was adopted by the Yazzie family when he was a newborn.

A full-blood Navajo, the baby was given to a family that shared his culture.

"I knew right away," mother Cynthia Lansing said, "This was my son."

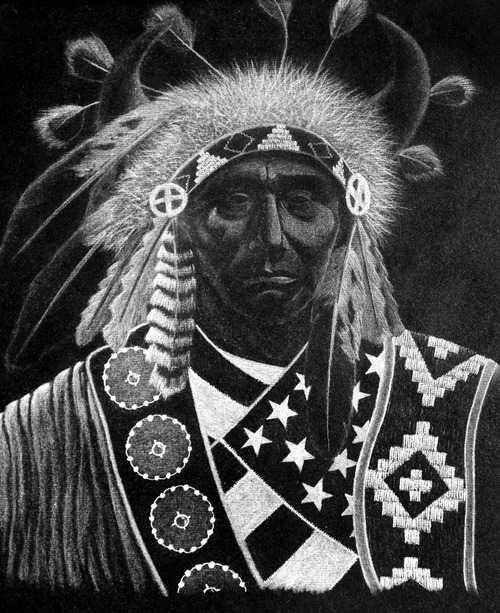

As Yazzie grew, he struggled to do things that came naturally to his siblings. He would watch as his older brother, Steven, or his younger sister, Jachelle, create beautiful works of art. Their parents, both artists, taught each of their five children how to draw and carve, how to create pottery and portraits.

"I remember him getting frustrated because his drawings weren't very good," father William Yazzie said. "But he just kept drawing, drawing, drawing. I think that's how he became so good — by sheer will."

His work paid off.

Yazzie won several youth awards for his artwork. He was well-known in local Native American art circles. His work still hangs in libraries and galleries throughout the West, his parents said.

But even with his success in art, Kaleb began to notice differences between himself and his parents and siblings. He began to ask questions, the elder Yazzie said.

"I told him that we never considered you adopted," William Yazzie said. "I considered him my own son, my own flesh-and-blood son."

The day before Kaleb died, his mother said, he was asking questions again.

She told him the truth: that his birth mother gave him up; that she never came looking for him; that the Yazzies had never thought Kaleb any different than one of their own; that she loved him.

"He took it so hard," Lansing said, her voice cracking with grief. "He got so quiet. Now, I'll never know what he was thinking."

—

Family • Cynthia Lansing never figured her son for a partier. She wonders today whether he was acting out — drinking and doing drugs — because of her confession.

She isn't the only family member who lives with guilt.

Steven Yazzie was sitting next to his younger brother at the movie theater when Kaleb's phone began to buzz.

He was getting text messages and calls from friends: Where are you? Are you coming?

Kaleb asked his brother if he wanted to join him at the party, but Steven declined. He said he had to work the next day.

Now he wonders what might have happened, what might have been different, had he been there.

"After Kaleb died, Steven blamed himself," said Stephan-na Lovell, the eldest sister. "I think he blames himself for letting Kaleb go on his own."

At the trial, the Yazzie siblings leaned on each other and held hands. They left the courtroom when the details of Yazzie's death became too much to bear.

Across the aisle sat the Karrs — a big family with tight-knit siblings not unlike their own.

The Karrs have declined to comment about the trial. But Aaron Karr, the brother of Adam, who killed Yazzie, and Ammon, who pleaded guilty to obstructing justice in the case, wrote a song that he recorded and posted on YouTube recounting his family's struggle.

In it he sings about his brothers as old home videos of the boys play: "They don't belong as prisoners in chains, they're my brothers," he sings. "Every day I pray for mercy and peace in their names. They don't deserve all this pain."

William Yazzie said he feels for the family who will also lose a son. Karr faces up to life in prison when he is sentenced Tuesday.

But the Yazzie siblings said they still feel too much anger to forgive.

"They're monsters," Lovell said. "How can you do that to another person? How can you stab someone to death and just leave them bleeding in the street?"

Throughout the trial, Karr's attorney said Yazzie was being "belligerent" and "obnoxious," that he had knocked a hat off the head of Karr's younger brother, Ammon, who was hosting the party.

This act — the tipping of Ammon's hat — was the spark that allegedly drove tensions higher and higher over the course of the night, defense attorney Richard Mauro told the jury. It was what led to the fight that led to the stabbing.

At this, the Yazzie family said, they had to suppress a laugh.

"That's how he is, he's playful, he likes to tease you; he would do that with my kids," Lovell said. "I remember they said that he combed the kids hair back and then stuck the hat back on the kid; that's not threatening. He was trying to be cool. They don't know him."

When Yazzie was asked to apologize and shake hands, he refused.

"He never ever liked to shake hands," his mother said. "He was never any good at it. He always wanted to hug instead."

—

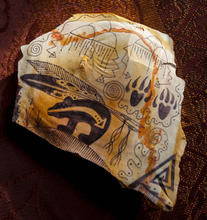

Moving on • In the Navajo tradition, eagles are a symbol of strength and positivity.

For the Yazzie family, that was Kaleb. Since his death, they've all struggled to move past the grief and the loss.

They put an eagle on his headstone. They've collected pieces of his art that feature the regal bird and kept them close.

On her birthday, his mother said, an eagle flew overhead.

"I knew it was Kaleb letting me know he was there with me," she said. "Ever since he died, whenever I feel sad, I see an eagle. That's how he sends his love, how he lets us know he's there."

On Tuesday, the Yazzie family will return to 3rd District Court to watch Adam Karr be sentenced for murder. It will be hard, they said, but they know Kaleb will be there with them, helping them stay strong.

Just down the hall from the courtroom, there is a sculpture of eagles soaring free.

Twitter: @Marissa_Jae