This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It's hard to miss Lt. Mike Thiede as he boards a train on a recent frigid Friday morning.

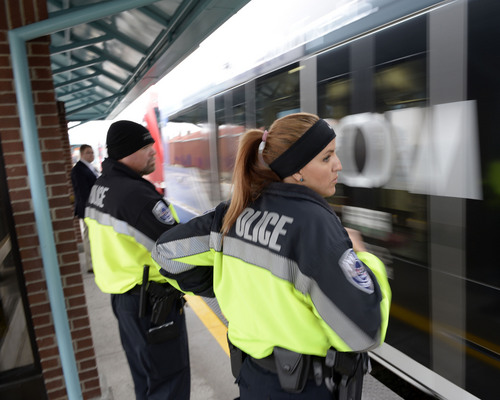

Dressed in a neon yellow jacket, the Utah Transit Authority cop stands out like a bright beacon on an otherwise drab day.

He wouldn't have it any other way, he says, noting that his presence alone helps deter crime along transit lines.

"[Criminals] know if they go on UTA, they're going to encounter an officer, talk to an officer, and they're going to go elsewhere," he said.

In 2012, UTA's 60 sworn officers worked 3,403 crimes along its lines.

While nearly 80 percent of all crimes were against the agency itself — problems with fare jumpers, criminal trespassers, and people riding with warrants from other jurisdictions — hundreds more involved more serious offenses that impacted passengers.

Passengers were more likely to be exposed to crime or run into a drunk or a drug user along one of the transit authority's bus lines compared with TRAX or the commuter-line, FrontRunner, a Salt Lake Tribune analysis of UTA's 2012 crime data found.

By-and-large people committed more serious offenses within 100 feet of bus routes than along TRAX lines or FrontRunner. (FrontRunner was the safest option, recording just three crimes within 100 feet of it. TRAX had nearly 1,110 crimes and the bus routes close to 1,900.)

But at the same time, UTA reported only a few handfuls of the most serious offenses — such as aggravated robberies and aggravated assaults.

"There could be a number of different reasons why crime is higher on certain modes of transportation," UTA spokesman Remi Barron said. "[Is it because] we've written more tickets there? Because there's just more activity on that line? Because there are more passengers, the ridership is higher? Or is that because it's just a higher-crime area?"

In 2012, nearly 17.6 million people boarded a TRAX train. About 21.2 million rode a UTA bus and about 1.9 million rode FrontRunner, according to figures provided by UTA. (Those ridership numbers don't include the Draper and Airport TRAX lines and the Provo FrontRunner line, all of which opened in 2013.)

That there were more crimes along bus lines didn't surprise Bill Tibbitts, associate director of Crossroads Urban Center, which provides services to low-income Utahns.

"There are dozens of bus stops for every TRAX stop," he said. "There are just so many more. The bus system still covers a lot more territory than the TRAX system."

Bus riders found themselves nearly four times more likely to have their bicycles stolen compared to TRAX. Police also responded to twice the number of drug crimes, more problems with alcohol, and nearly four times more lewdness, sexual battery or public urination violations near buses, the Tribune analysis found.

"There are so many more stops and so many of them are more isolated," Tibbitts said. "I think at the TRAX stops there is a bigger police presence, but there are [also] more people watching. It would make sense that people are more likely to prey on somebody when they see them by themselves at a bus stop than when they're with a group of people at a TRAX stop."

Thiede said the Transit Authority's basic enforcement efforts typically revolve around the rail lines because they connect everything.

"We have so many people moving by rail," he said. "If we focus on the bus side, we're missing all those people."

UTA's 2012 crime numbers reflect that philosophy with the majority of all crimes — including bus crimes — occurring in proximity to the TRAX arteries.

But one area that had a smaller amount of crime than one might expect was UTA's free-fare zone — the designated area downtown where passengers can ride public transit free at the heart of the UTA's transportation system.

A heated debate in 2012 ensued about whether free bus service should be ended with UTA officials arguing the perk increased theft-of-service crimes by allowing unsavory people to hop on board to keep warm, or to beg or bother passengers. UTA officials argued that those passengers would then refuse to pay once outside the free-fare zone.

The Tribune analysis found only about 8 percent of all of UTA's crime occurred within the free-fare zone.

The agency reported 103 crimes along free bus routes compared with 259 along free TRAX routes.

The most frequent crimes along free bus routes involved criminal trespassing, alcohol, fare jumping and assault.

Tibbitts said his agency recently surveyed 272 people who use his organization's food pantry and nearly 42 percent of those reported they used public transportation at least four times a week.

"When people are concerned about the [UTA] service, it's usually [that] it ends too early in the day or doesn't go where they need to go [or cost]," he said. "Safety, I don't think, is the top concern as compared to those other factors."

Barron said passenger safety is a top priority along the line, but he said there's no reason people should feel unsafe on their lines.

"One of the reasons that we do have one of the safest systems in the country is because our transit officers do a really good job at quickly responding to incidents," he said. "We encourage people to call our [dispatch line]. The fact that we have officers up and down our train routes, our bus routes, checking fares and performing customer service means they're really close to what's going to happen."

Thiede said UTA officers use fare enforcement in order to help deter the more serious offenses.

"You said we have the reputation of being glorified ticket givers," Thiede said. "I'm OK with that. That behavior is lowering more significant types of crimes."

He said by enforcing the seemingly minor offenses, it ensures officers are visible and deters unwanted activity because criminals know police are always around.

"We really believe that our system is one of the safest in the nation," Barron said. "We think it's largely because of the job that our transit police do. And the dedication the officers have to making sure the lines are safe."

Tribune reporter Tony Semerad contributed this article.

Twitter @sltribjanelle —

About this story

The Salt Lake Tribune initially requested the Utah Transit Authority's 2011 crime data more than a year ago under Utah's open records laws as part of a countywide crime-mapping project. UTA denied The Tribune's request.

After a ruling from the State Records Committee deemed UTA's crime data public and ordered it to be provided free of charge, UTA filed a civil lawsuit against the requester, reporter Janelle Stecklein; her employer, The Salt Lake Tribune; and the State Records Committee, seeking a judge's order reversing the decision. UTA argued in part that it could not provide the crime data because it was stored inside one of its third-party vendor's databases that UTA could not access.

The Tribune and UTA reached a settlement in October 2013. As part of the settlement, The Tribune dropped its 2011 request and instead agreed to accept UTA's 2012 crime data. In return, UTA pledged it would work with its vendor to make the records easily available to the public going forward and placed a cap on what it would charge for such data going — should it not be able to work out a solution with its vendor. The agency also compiled the 2012 crime records The Tribune was seeking in exchange for a mutually agreed-upon fee.

Those records were then used for the analysis in this story.