This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

We search Google billions of times a day, send out millions of tweets an hour and upload 100 hours of YouTube video every minute, so perhaps the mind-boggling fact that 90 percent of the world's data has been created in the last few years shouldn't be too much of a surprise.

With the right kind of analysis, that avalanche of data is also massively valuable. It has the potential to sell more stereos, reduce driving during the infamous Salt Lake Valley pollution episodes and even cure disease.

"It's becoming a more and more integral part of how most of the big decisions are made," said Jeff Phillips, an assistant professor of computing at the University of Utah. "The hard part is combing through all the data and organizing and managing and updating the data."

Phillips is the coordinator of a new master's-level certificate in big data approved by the U.'s Academic Senate this week and said it will give students skills employers are increasingly clamoring for. Set to begin in the fall, it consists of five courses in data mining, machine learning, database systems, visualization and advanced algorithms, and is aimed at both graduate students and professional computer scientists.

The new certificate, which needs the approval U. trustees, builds on a strong history of computer science at the U. and the state's increasing popularity as a location for large data centers — including the National Security Agency's massive Bluffdale facility.

The school also offers a separate undergraduate certificate in data center management meant to train employees with the specialized skills to take care of those large centers attracted to the state by cheap power and a favorable climate.

The new big data certificate, on the other hand, would train analysts — jobs something like the insurance actuary position Sterling Fuller, a 28-year-old statistics master's student, is hoping to get.

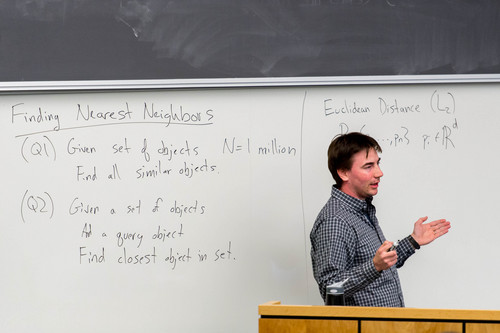

"For me, it's looking at a bunch of different businesses and what they're looking for," said Fuller, speaking before the start of his class in data mining, one of the courses that will be part of the new big data certificate.

Fuller isn't the only one seeing companies looking for big data skills. In a report released in 2011, consultants McKinsey & Co. estimated that the country will have a shortage of up to 190,000 workers for deep analytical jobs in the coming years, as well as 1.5 million managers and analysts who know how to use big data to make decisions.

Locally, companies like Adobe, Goldman Sachs, Zions Bank as well as the NSA have approached the U. seeking employees with data analysis skills, Phillips said.

But as data are increasingly available, analyzing and using it ethically is also an issue. Phillips said the certificate will include case studies of "people who have been a little bit overzealous trying to share this data, or do too much with it." Automatic safeguards like eliminating personal information from data and throwing it away after a certain number of months can help.

"When dealing with issues, it's no longer on a small enough level that you can hand-audit these sorts of things," Phillips said.

As the amount of data we produce increases, so does the U.'s investment in studying it, as evidenced by the establishment the Center for Extreme Data Management and Visualization and new faculty hires.

"I think we're well positioned to work in this area," said Julio Facelli, a professor and vice chairman of the department of Biomedical Informatics at the U. School of Medicine. That department is planning its own course program aimed at medical data science — an industry that could be worth up to $300 billion, McKinsey estimated.

The exploding amount of information from ever-cheaper genome sequencing is a major source of big data in the biological sciences, while in medicine, analysts must make sense of a host of overlapping symptoms and risk factors.

"The challenge with medical science is really with the complexity," said Facelli. Computers don't process context as well as the human brain can.

"The problems we face in medicine today are very, very challenging," Facelli said. "We need to figure out what to do with the data."

Twitter: @lwhitehurst