This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

At the height of the 2008 presidential election, Jon McNaughton had a vision.

In his mind's eye, the Provo-based artist saw Jesus Christ holding the U.S. Constitution in the midst of the Founding Fathers and other famous Americans.

The finished painting with its didactic message went up for sale last summer and instantly became a lightning rod for the ongoing debate about the Founders and their faith.

Were the framers orthodox Christian believers who intended to build the new nation on theological principles, or were they religious skeptics eager to cast off centuries of tradition? Was Jesus Christ guiding their actions, or was he merely an ancient moral teacher?

This weekend, as the country celebrates its birth, the verbal battle between these two camps seems more virulent than ever.

McNaughton's painting was pilloried on The Huffington Post, a liberal website, and by Bill Maher, the anti-religion talk-show host. An e-mail and YouTube explanation of the painting went viral, amassing more than 3 million hits. Conservative commentator and fellow Mormon Glenn Beck mentioned it on his Fox show and has a print of it hanging in his home.

McNaughton insists his critics misunderstood the painting's meaning.

"I was not suggesting that there should be no separation of church and state or that all the Founding Fathers were Christian," he says. "I just meant to say that the Constitution was divinely inspired and that the Founders believed society should be based on Judeo-Christian values at its core."

McNaughton is not alone in his approach to the Constitution and Christ.

According to a 2007 national survey by the First Amendment Center, 65 percent of Americans believe that the Founders intended the United States to be a Christian nation, and 55 percent believe the Constitution established a Christian nation.

A battle over colonial history has erupted in Texas, where Christians such as Don McLeroy argue passionately that their perspective on American origins

should be included in public school textbooks.

"The men who wrote the Constitution were Christians who knew the Bible," McLeroy told Russell Shorto of The New York Times in February. "Our idea of individual rights comes from the Bible. The Western development of the free-market system owes a lot to biblical principles."

Meanwhile, critics such as Brooke Allen, writing in Moral Minority: Our Skeptical Founding Fathers , argue that the Founders' faith was one step away from atheism, hardly the religious fervor of an evangelical camp meeting.

Recent scholarship, though, provides evidence that the true story never is as simple as either side argues. After all, faith is at once personal and public. The revolutionary generation was a diverse group, and history is messy.

Religious roots » At its beginning, the new nation was awash in various forms of Protestantism, with a smattering of Roman Catholics and a few Jews. The Northeast was dominated by Congregationalists, the descendants of Puritanism, and Quakers. The farther south one went, the more Anglican -- or eventually Episcopalian (the American branch of the Church of England) -- it became.

Pennsylvania was famously tolerant of all faiths, but nine of the 13 colonies -- including Virginia -- had state-supported religions.

It is not surprising, then, that four of the first five U.S. presidents -- Washington, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe -- all were raised Anglicans, while Adams, from Massachusetts, was Congregationalist and, later, Unitarian.

Meanwhile, deism was sweeping the educated classes of Europe and came to this country, influencing Christians in every denomination. That movement rejected Christianity's supernaturalism -- the idea that God was incarnated in Jesus, the Trinity, the miracles of Jesus, the virgin birth and the resurrection. But it did retain a belief in God, in virtue and in life after death.

Most of the prominent political figures were deeply influenced by deistic teachings, variously combining their Christianity with the rational reasoning of the Enlightenment. Thomas Jefferson, for example, shared the deistic disdain for what he considered superstitions or "hocus-pocus" elements of Christianity but loved the faith's oratory and ethics and considered Jesus the most important moral teacher of all time.

The man who penned the Declaration of Independence went to services but "tuned out anything he didn't believe in," says David L. Holmes, professor of American religious history at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Va. "He would not stand as godfather in Anglican confirmations because he would have had to answer for the baby's faith, and he would not do that."

James Madison was sent to the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), which was the training ground for Presbyterian clergy, as a way to avoid the skeptics of William & Mary. He studied theology as well as Latin and Hebrew, but also learned about Enlightenment thought. When he returned to Virginia to study law, Madison was appalled at the treatment of religious dissenters and passionately defended liberty of conscience. He was never confirmed in a faith and rarely spoke of his own religious feelings, but he did attend some Episcopal services.

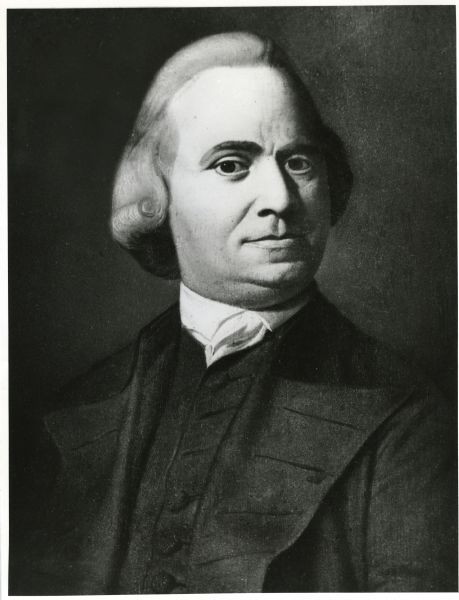

Some of the most important revolutionary figures such as Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry, though, remained committed, orthodox Christians, Holmes says. Their stories have been overshadowed by the deists and too often dropped from the narrative.

Today's evangelicals are trying to recover that part of the story, he says, and rightly so.

Birthing a nation » The plurality of faiths that landed or sprouted on American shores meant that no one group had the upper hand, and each was worried that another would dominate. They all preferred no national religion to giving preference and power to a chief competitor.

Keenly aware of sectarian squabbles, the Constitution's framers sought to guarantee the utmost freedom to all parties, even non-Christians.

"Above all, they valued freedom of conscience and despised religious tyranny," writes Holmes in his 2006 volume, The Faiths of the Founding Fathers , an Oxford Press publication that immediately sold out after Beck mentioned it.

The Founders chose not to create an exclusively Christian nation when they had the chance, Holmes says. "It would not have passed anyway. There were too many differing beliefs in the Continental Congress and, even though most members were Protestants, the churches had rivalries among themselves."

Jon Meacham, author of American Gospel: God, the Founding Fathers and the Making of a Nation, agrees, calling the idea of a Christian nation "wishful thinking."

He cites the Treaty of Tripoli -- a pact with Muslim nations initiated by Washington, completed by John Adams and ratified by the Senate in 1797 -- in which the Founders declared that "the government of the United States is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion."

Instead, they did something better.

"They found a way to honor religion's place in the life of the nation," Meacham writes, "while giving people the freedom to believe as they wish, and not merely to tolerate someone else's faith, but to respect it."

That attitude's most visible symbol was Benjamin Franklin, who became known as the "apostle of tolerance," according to his biographer, Walter Isaacson.

The multidimensional Franklin donated to the building funds of every church and sect in Philadelphia, including a new Jewish synagogue.

During the July Fourth celebrations of 1788, Franklin arranged a joint venture for clergy of all faiths. Then, when the aging patriot was confined to his bed, the parade marched by Franklin's window, Isaacson notes in Benjamin Franklin: An American Life , and, for the first time, "the clergy of different Christian denominations, with the rabbi of the Jews, walked arm in arm."

The first father » The fight seems most heated when it comes to claiming Washington.

"It is very important for some writers," Holmes says in an interview, "that he be shown not a believer and, to others, a firm orthodox Christian."

Ultimately, no one can get inside people's minds to find out what they really believe, he says, "but you can watch what they do, read what they write, watch them in times of crisis and read what others say about them. Did they attend services, take Communion, refer to the divinity of Jesus or believe in the Trinity?"

After reading Washington's journal and letters as well as statements by his pastor and other ministers of the time, Holmes concludes that the first president straddled orthodox Christianity and deism.

"I do not believe that any degree of recollection will bring to my mind any fact which would prove General Washington to have been a believer in the Christian revelation," recalled the chaplain of the Continental Congress in 1833.

The president attended Episcopal services, Holmes writes, but never was confirmed in the church and, unlike his wife, Martha, didn't stay around for Communion. He never mentioned Jesus,

the historian notes, but did believe ardently that the "almost miraculous victory of the colonists as well as the successful creation of the new republic stemmed from the invisible workings of providence," which he views as "a benevolent, prescient, all-powerful God who created life and guided its development, but who remained at least partially distant and impersonal."

Shortly after Washington's death in 1799, evangelical Christians began to depict the president as a devout and prayerful leader. They told of him hosting Communion services before battles, spending the night in prayer, stepping into rural churches to inspire local congregations and of going into the woods to pray in solitude.

Such stories may have elevated the Father of the Nation to a near-mythical stature and created enduring legends. The trouble is, according to Washington contemporaries such as Jefferson and Madison, they are not true.

A different time » It is important to remember, scholars say, that history is not just a mirror of the present.

"It's interesting to me how charged this question has become recently," says University of Utah history professor Eric Hinderaker. "That's much more a reflection of our political environment than theirs."

The question of religious adherence, he says, was not "a dividing line among people in the constitutional era."

"John Adams would not have been threatened by the idea of Thomas Jefferson applying the power of reason to the profound mysteries of life," he says. "And even though Jefferson and Franklin might have seen Christianity as a set of beliefs encrusted with fabulism, they also believed that religion had salutary effects on a society and that strong churches supported the social order."

Though it is impossible to fully recover a sense of their worldview, the Founders' accomplishments continue to find resonance even in today's fractious world, riven by religious conflicts.

"The Founding Fathers struggled to assign religion its proper place in civil society -- and they succeeded," Meacham writes in American Gospel. They balanced the "promise of the Declaration of Independence, with its evocation of divine origins and destiny, and the practicalities of the Constitution, with its checks on extremism," he writes, which remains "perhaps the most brilliant American success."