This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2009, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It wasn't yet today's Internet, but 40 years ago technicians made the final connections between three computers in California and one at the University of Utah that would lead to the transformation of human communication.

The fledgling network they created inspired other government-backed and private projects that by the early 1990s would merge to become the Internet and revolutionize how we work and play.

How the U. found itself at the beginnings of this revolution in the late 1960s is a story less filled with deliberate calculation than with chance, coincidence and a flood of federal money that followed a native son home.

If two other California computer labs had been more supportive of the concept of connecting their computers to others for the purposes of communication, Utah's place as we acknowledge the 40th anniversary of the Internet would have been much less prominent.

"Those four sites, all supported by my office, were the first sites that showed real enthusiasm for the ARPANET projects," said Robert Taylor, who in 1966 took over an agency overseeing the start of a network that would become the Internet. "Many of the other places we were supporting were less enthusiastic because they didn't want to share their computer cycles with anybody else."

Although there is no fanfare at the University of Utah marking the 40th anniversary this month, back in 1969 the campus was a hotbed of computer activity.

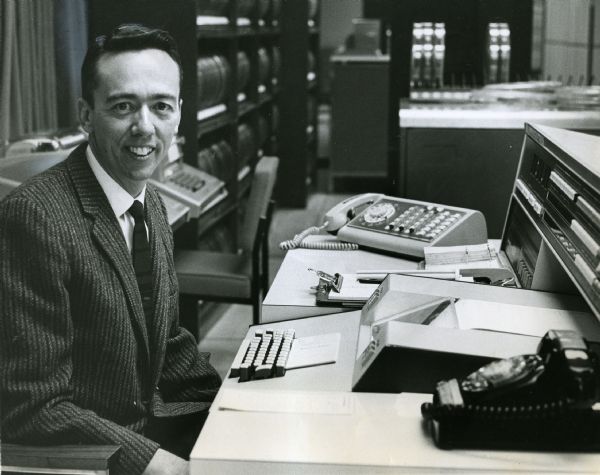

Two key events triggered the U.'s role in the Internet's birth: the return of Utah native David C. Evans to create and lead the school's computer science department and the arrival of millions of federal dollars he brought with him.

A response to Sputnik » Evans was born in Utah and earned his doctorate in physics from the U., worked at Bendix Corp. and then went to the University of California at Berkeley as a professor. In the years after ARPANET, he was credited with helping create the state's technology industry and fostering technological innovation through his graduate students whose influence has been felt industrywide.

Evans brought with him money from the Pentagon through the Advanced Research Projects Agency, or ARPA, which President Eisenhower created in response to the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957. Eisenhower charged ARPA with helping the U.S. gain world leadership in scientific research. The agency had millions of dollars in its budget to spread to various projects.

Part of that budget paid for the Information Processing Techniques Office, which J.C.R. Licklider directed in 1962. The computer scientist used the office's newly fattened checkbook to promote development of "time-sharing," a concept of creating remote connections to computers that would enable researchers to more widely use limited computing resources.

Licklider began to refer to his vision as the Intergalactic Computer Network, which encompassed time-sharing and a host of other potential uses for ARPA computers nationwide.

Licklider handpicked another computer scientist, 26-year-old computer graphics pioneer Ivan Sutherland, who later would make his mark in Utah, to replace him at ARPA when Licklider left in 1964.

By 1966, ARPA was funding 16 computing projects around the country. In June 1966, Robert Taylor took over after Sutherland accepted a post at Harvard. He conceived of the ARPANET, a network that would turn computers into communication devices, not just data crunchers. He imagined this wide-ranging communications tool after seeing how scientists coalesced into a community at facilities where his office was funding research. They had e-mail and chat rooms, but use was restricted to those who were connected to only one computer.

Taylor also grew frustrated in his own office, where he had three terminals connected to three computer systems at ARPA sites, forcing him to move to different terminals and log on if he wanted to use a specific computer's programs or to communicate with people at the various sites.

"It doesn't take much of an imagination to realize this was kind of silly," Taylor said by telephone from California, where he is retired. "You should have only one terminal that can go to any system that's on the network."

Back to Utah » Evans managed one of the ARPA-funded centers at Berkeley, before he was lured back to Utah by U. President James C. Fletcher in 1966 to start a similar program in Salt Lake City.

"Dave recognized his mission would be really facilitated here because he had presidential backing and no bureaucracy to get in his way," said computer-science professor Richard Riesenfeld, who arrived at Utah in 1972 and would later chair the department.

Taylor remembers meeting with Evans about his return to his home state. Evans, who died in 1998, worried about leaving ARPA money behind in California.

"He said, 'So I'm thinking about leaving Berkeley and I wanted you to know about that.' I said, 'You have my support in going to Utah. You decide what kind of work you want to do there and send a proposal in, and let's see if we can fund it.' He did that, and that's how the computer graphics work funded by ARPA got going."

Evans' records from the U.'s archives show that the school received about $8 million through 1970 from ARPA for computer research, with the emphasis on developing computers to produce three-dimensional graphics at a time when they were capable mostly of creating only text. The money bought a large mainframe computer for the university.

Taylor dreamed of connecting all the ARPA-funded computer projects, creating a powerful communication network where researchers could easily talk to each other and exchange information, as well as share files. In 1968, he persuaded his boss to foot the bill for such a network.

That same year, Sutherland left Harvard to join Evans at the University of Utah because he wanted to develop computer graphics. They founded Evans & Sutherland, a private company that created systems such as flight simulators for the military and that still exists today. Sutherland lives in California but does not grant interviews.

Envisioning a network » Despite its great promise, Taylor had trouble getting all the ARPA sites to buy into his vision. He succeeded in selling his idea for the ARPANET to West Coast schools to hook up four original "nodes" of the system to test it before expanding it to the other ARPA sites.

"The Western sites seemed to be more open, just like the West is more open," Taylor said.

UCLA and the Stanford Research Institute were named as nodes, but researchers at Stanford University and Berkeley were less than enthusiastic about the network. That led to designating the final two nodes at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the University of Utah. But many issues capable of derailing the project remained.

Representatives from each site, including U. graduate student Steve Carr, met to work out technical details. He had followed Evans from Berkeley to Utah.

"The working group was concerned mainly with getting the basic capability of the network working, which was so minimal by today's standards. It basically allowed you to log in to somebody else's computer," Carr said in an interview from California, where he now works.

Small computers called IMPs (Interface Message Processors) were delivered in 1969 to connect each of the four sites, setting the stage for UCLA and the Stanford Research Institute to be the first linked on Oct. 29 to the ARPANET.

That September, Taylor had accepted a job from Evans at the U., where he was to put all computer programs under one office. Taylor would be in Utah only about a year before taking a job with Xerox, but his impact on the marriage of the U. and ARPANET was deep.

The date when the U. was hooked to ARPANET is unclear. Larry Roberts, who took over from Taylor and oversaw the actual startup of the network, said in an e-mail that he did not record the exact date but that it was sometime before the end of 1969.

Alan Kay, who participated in ARPANET's design while working on a doctorate at the U., puts it in the month of December.

The first Internet » "Utah was the fourth node, and this made what we considered an important step in networking -- having four computers up and interworking," Roberts said. "The accomplishment that we felt from adding Utah was that we had the largest network ever put together, established from scratch in one year, 1969."

Riesenfeld, the U. computer-science professor, admits that his view of the ARPANET is more "idiosyncratic." He arrived at the U. just as the network was being expanded to institutions nationwide. He regarded it then as a technical failure, and still does today.

"It was outrageously expensive. It was abysmally slow."

Good thing the government of that era was willing to throw money at the Internet precursor without worrying about results, he said, because otherwise it might have quickly folded.

"I've always say that today the ARPANET would have been scuttled. It was too expensive and took too long for the vision to develop."

He said the system was the butt of jokes from scientists who thought the money could be used for more fruitful scientific research.

"Then slowly it was realized, 'Look, this really isn't working per the original concept but it has engendered a very close community,' " Riesenfeld said. "This was a fraternity of top computing people, and the impact was very large in terms of the sociology of science."

Beyond the ARPANET, the talent and money that had gathered at the U. in the late 1960s also would pioneer three-dimensional computer graphics, spawn the creation of digital recording and graduate doctoral students who founded Pixar Animation Studios, Adobe Systems, Silicon Graphics and WordPerfect, among others. It was a magical time for computer science at the university, where today the program still enjoys a strong reputation.

For its part, the ARPANET shut down by 1990 as other public and private networks it inspired were merging to form today's Internet. Although forgotten by some, it is still considered an achievement by many.

"Of course we added many more nodes in 1970 and later," said pioneer Taylor, "but the first four always stood as an important milestone in networking."

tharvey@sltrib.com" Target="_BLANK">tharvey@sltrib.com

1957 » Soviets' Sputnik launch exposes how far U.S. had fallen behind in scientific research.

1958 » President Eisenhower creates the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) at the Department of Defense to fund scientific research. A key component is the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO), which funds computer development projects.

1964 » Original IPTO head J.C.R. Licklider, who conceived of creating "time-sharing" to link researchers far away to ARPA computers, leaves ARPA. Ivan Sutherland replaces him.

1966 » David Evans joins the University of Utah, founds the computer-science department and attracts millions of dollars in federal funds for research.

1966 » Robert Taylor replaces Sutherland at IPTO and wins approval for vision of ARPANET, a network that would turn computers into communication devices, not just data crunchers.

1969 » The University of Utah is chosen as one of four original "nodes" of the ARPANET along with UCLA, the Stanford Research Institute and University of California at Santa Barbara.

Oct. 29, 1969 » The Internet is born with the first message sent over the ARPANET from UCLA to the Stanford Research Institute.

December 1969 » All four of the original computers are connected; the University of Utah is the final one.

1990 » ARPANET shuts down.