This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2009, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Reading » Thinking of summer as a lazy time for reading seems so, well, so last-century. It strikes us that the balmy days of Indian Summer --- when the kids are back in school, when your boss has already returned from her vacation -- seem like an even better time to steal away with a book and make the most of a couple of uninterrupted hours. Fact is, all summer we've been fantasizing about great reads on the other side of all the hikes and outdoor excursions and other adventures of the hot weather days. Which is why we've been collecting new titles, books with release dates from April to September, and have settled down for these review sessions. -- The Salt Lake Tribune

Master of nervous conversation returns

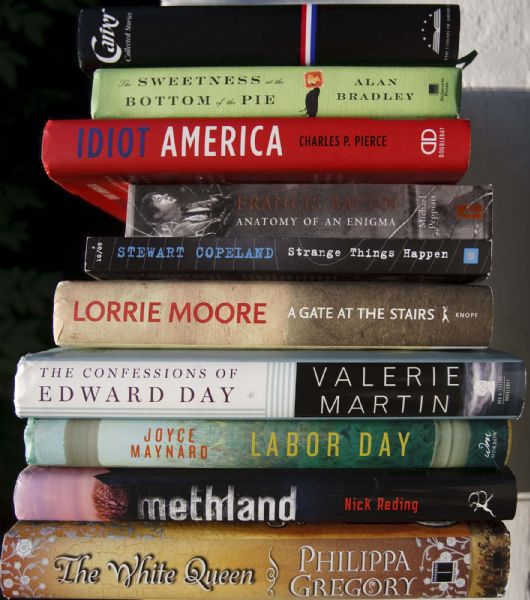

It was only a matter of time before the most troubled angel of the short-story form of 1980s American got a sumptuous repackaging of his best work. Like Ernest Hemingway and John Cheever before him, Carver's Collected Stories (William L. Stull and Maureen P. Carroll, editors; $40, Library of America, 1,019 pages) hold a bounty of acute observations in spare prose. Unlike those masters, however, Carver moved the goalposts several yards beyond through dialogue that shifted up and down myriad floors of subtext and an almost frightening honesty about human feelings and emotions. Carver's stories alone are reason enough to buy this pricey volume. As an added bonus, there's a fascinating glimpse at the writer-editor relationship between Carver and his most trusted cipher, literary maven Gordon Lish. The never-before published collection "Beginners," Carver's original draft of the stories that would later become "What We Talk About When We Talk About Love," reveals not only the surprising degrees to which Lish sharpened his most famous talent but, more crucially, the big-hearted depth of a great author.

-- Ben Fulton

How's this for a heroine?

Move over Barbara Havers, Tess Monaghan, Kay Scarpetta. You may be quirky, but you can't compete with Flavia de Luce in Alan Bradley's The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie ($23, Delacorte Press, 373 pages), arguably the most captivating female sleuth to yet be introduced in a crime novel. Flavia, 11, is the little sister you want to smack. She's as devious as she is determined once a strange series of events -- most notably a murder -- occur at Buckshaw, the musty English manor she shares with her widowed father and sisters. Upon discovering a dead body in Buckshaw's garden, Flavia matter-of-factly notes her lack of fear at the discovery. "This was by far the most interesting thing that had ever happened to me in my entire life," she says. Not one to let an opportunity pass, she sets out to solve the crime -- and succeeds. My advice? Stay out of this engaging little girl's way, but make sure to follow along. -- Lisa Carricaburu

Flesh and brush

Peeking into Francis Bacon's irreverent artistic drift in Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma (Michael Peppiatt, $16.95, Skyhorse Publishing, 464 pages), one finds lovers and bullfights and crucifixions. His father had him horsewhipped. He was a "weakling" asthmatic brought up in Britain and Ireland shaped from the get-go by the violent temperament of a warring century. It wasn't until he'd survived adolescence that he could make the paintbrush his primary instrument of expression. That the reader wants to peer on is a testament to the evocative skill of Michael Peppiatt, his longtime friend turned forensic documentarian. Peppiatt peels back layers of Bacon's iconoclastic persona, tracing his worldly twists and turns, his volatility and polarizing exploits, all of which undergird his brilliant artistic record. What comes alive are the underpinnings of a difficult genius: his personal contradictions, his self-perpetuated enigmatic presence, his expeditionary and nearly uninhibited sexuality. Bacon's was a life lived to the extreme. It's retold with elegance and introspection that keeps the hagiographic impulse at bay.

-- Rudy Mesicek

No drummer jokes, please

If you are looking for a standard memoir from a member of the legendary rock group The Police, keep on looking. In Strange Things Happen: A Life with the Police, Polos and Pygmies ($19.99, HarperStudio, 322 pages), drummer Stewart Copeland proves he has always been unconventional, whether it's his playing with the so-called "traditional grip" (which is, oddly enough, one of the least traditional) or his post-Police work composing quirky soundtracks and operas. The autobiography jumps decades back and forth but still manages to reveal who he is and how music is made. From growing up as the child of a CIA officer in Lebanon to the recent triumphant Police reunion tour, Copeland is an engaging, frank author with an eye for characterization and an ear for the outrageous. And yes, there are plenty of behind-the-scene anecdotes about Sting.

-- David Burger

Riding our dinosaurs to church

It used to be, writes Boston Globe staffer and NPR commentator Charlie Pierce, that America's crackpots were relegated to the sidelines, their ideas absorbed into the melting pot where they couldn't hurt anyone. Now, as Pierce details with wit and fury in Idiot America: How Stupidity Became a Virtue in the Land of the Free ($26, Doubleday, 304 pages), the crackpots have taken over talk radio, cable news and the halls of power -- all claiming to be experts. "And if everyone is an expert, then nobody is," Pierce writes, "and the worst thing you can be in a society where everybody is an expert is, well, an actual expert." Pierce's travelogue of bad ideas spoken loudly takes us from a creationists' museum (complete with saddle-wearing dinosaurs) through Sarah Palin's Alaska to Terri Schiavo's nursing home -- and ultimately through the run-up to the Iraq War, where idealogues who wanted a fight drowned out the grown-ups who (correctly) predicted the quagmire to come. For all the anger in Pierce's book, his prevailing emotion is hope for some actual smart people, following the footsteps of James Madison, to steer America away from the brink. -- Sean P. Means

Ego on stage

Jealousy. Envy. Resentment. And don't forget ego, which is what Valerie Martin's eighth novel is mostly about. The Confessions of Edward Day ($25, Doubleday, 286 pages) takes us inside the head of a handsome and talented actor performing in New York City in the 1970s. Through Edward Day, we relive a vital era in American theater during which aspiring students of great method acting teachers, such as Stella Adler, pursued their art with noteworthy intensity. Edward's own quest for artistic perfection -- and a paying job -- is juxtaposed against that of fellow actor Guy Margate. Edward is disarmed by how much Guy looks like him -- and by Guy's obvious interest in Edward's beautiful actress girlfriend. The two compete viciously for everything that has meaning in their lives to a chilling end that leaves us intrigued by these narcissistic people but questioning whether we'd ever want them as friends.

-- Lisa Carricaburu

Teen beat - -- and pie crust

Joyce Maynard admits to being a hopeless romantic, and that trait is on full display in Labor Day , ($24.99, William Morrow, 241 pages), her novel about a 13-year-old boy who lives with his divorced mother, also a hopeless romantic. The story is narrated by Henry, and takes place over six days that span Labor Day, hence the title. As the rather predictable plot unfolds, both Henry and his mother will have significant encounters with the opposite sex. The best part of this easy-read is the way Maynard gets inside the head of an adolescent boy who is grappling with his own identity and the mysteries of sex (while revealing the secrets of making perfect pie crust). She does a credible job of developing his character and that of his neurotic mother, even if we're not surprised by the ending.

-- Anne Wilson

Midwestern modesty

Those of us who are Mooreofiles -- and let's face it, readers of contemporary fiction who don't love Lorrie Moore just haven't read her insightful prose, studded with ironic humor -- have been holding our collective breaths awaiting her next volume. The master of short stories returns with A Gate at the Stairs , ($25.95, Knopf Doubleday, 336 pages), her first novel in 10 years, and it's a richer, expansive and singularly quirky feast. Quirky in all the best ways, this shaggy dog story unfolds through the eyes of a gentleman farmer's daughter, Tassie Keltjin, who is looking through the fun house windows of a Midwestern college town. Under the shadows of 9/11, Tassie, a humanities major, finds herself barely qualified for a babysitting job, and once she's hired, her new position sinks her deep into a politically correct adoptive household, where she sharply observes everything but the troubles that will come to divide her work family and her own. This wry and heartbreaking book rests on its wholly original narrator, whose insight serves to pour acid into the vulnerable cracks in our collective psyches, before teaching us, once again, to nurse ourselves back to sanity through the comfort of our own authentic, vulnerable wisdom. -- Ellen Fagg Weist

Power, love and history

Philippa Gregory's The White Queen ($25.99, Touchstone, 408 pages) explores the struggles, mysteries and passions behind England's War of the Roses from an unfamiliar perspective -- that of a woman. Elizabeth Woodville, who married King Edward IV in secret in 1464, narrates this story of fatal ambition, manipulation, love and war. Like many of Gregory's other novels, the events and characters are real but the dialogues, details and emotions imagined. Hang on for the ride: The second half of the book is better than the first. -- Lisa Schencker

Meth and the red, white and blue

Nick Reding's exhaustively reported Methland: The Life and Death of an American Small Town ($25, Bloomsbury, 272 pages) focuses on Oelwein, Iowa (pop. 6,159), revealing how the story of one heartland burg ripped apart by the ravages of the methamphetamine epidemic is really an all-American story. Reding's research is devastatingly meaty, ranging from the meth reporting battles of rival newspapers in Portland, Ore., to glossing Orrin Hatch's drug company protectionism, to outlining how the queen of Midwestern crank (Lori Arnold, a high school dropout who is the comedian Tom Arnold's sister) built her far-reaching empire. For all of his facts, Reding smartly never takes his eyes away from the small-town characters who serve as metaphors to let us see how the bigger story of economic failure addicts and indicts us all.

-- Ellen Fagg Weist

Two-minute recommendations

Lorrie Moore's first novel, Anagrams, is worth revisiting for the ironic, breathtakingly vulnerable heart of its female character, Benna Carpenter, who presents readers with such diamond-sharp insights and fierce vulnerabilities that we start to understand the force of her imagination. Wallace Stegner's classic Angle of Repose has even more heart in re-reading, as the 1972 Pulitzer-prize winning novel illuminates what it means to be a transplanted westerner, and how what we leave behind is as important in a relationship as what we are struggling to build.

-- Ellen Fagg Weist

It all starts here, in Stories of Anton Chekhov. Or, at least the short story as we know it does, anyway. The aching fragility of Chekhov's art was always something of a closed door thanks to lackluster translations of the past. Team Larissa Volokhonsky and Richard Pevear nail it open in these stories of death, adultery, poverty and the tragedy of human pettiness. Taking Fitzgerald's dictum about the rich to its logical conclusion -- "they're different from you and me"-- Cheever set his course for the American suburbs on a search-and-destroy mission. Read John Cheever: Collected Stories and Other Writings, and you'll see: The literary fall-out remains both beautiful and devastating.

-- Ben Fulton

Bob Dylan's first book, Chronicles: Volume One, shares the herky-jerky narrative of Stewart Copeland's memoir but offers an insightful, penetrating look into the mind of one of America's most private and enigmatic artists. Not for the faint of heart, Motley Crue: The Dirt -- Confessions of the World's Most Notorious Rock Band is written by the four members of the infamously decadent rock band. What makes this 2002 tome unique is that the members, especially bassist Nikki Sixx, take no advice from publicists and give the reader a vicarious look at rock and roll excess.

-- David Burger

Philippa Gregory's The Other Boleyn Girl tells the story of England's move away from Catholicism and the annulment of a royal marriage as narrated by Mary Boleyn, sister to Anne Boleyn, who was wedded to and eventually beheaded by King Henry VIII.

-- Lisa Schencker