This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2009, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Vernon, Tooele County » Mount Timpanogos rose like a snowy apparition in the distant east as we turned off Highway 36 and headed west on the Pony Express Trail. From this lonely vantage point, just north of the berg of Vernon, it was difficult to believe that a million or so people live at the base of the Wasatch Range.

The area west and north of this spot, where Pony Express riders once raced across the desert, includes bombing ranges and the Dugway Proving Grounds, where nerve gas and biologic toxins were once tested. Several thousand sheep mysteriously died near here in the aptly named Skull Valley in 1968, likely from nerve gas.

Yet Peruvian herders on horses still tend their flocks with dogs here in the spring. One large woolly sheep rested under a wooden sign pointing to Dugway, blissfully unaware of the fate of his predecessors four decades ago.

Our two-day, 524-mile journey through Utah's west desert, along the Pony Express trail to Wendover and the Salt Flats, then north along the west and north borders of the Great Salt Lake, was bracketed by death. In between, there were ghost towns, salt flats, casinos, and modern art. People were scarce in this geometric landscape created by clouds and mountain ranges, though the few we met told interesting tales.

Death and a history lesson » One of our first stops was a pet cemetery, which we figured was built near Lookout Pass by some present-day animal lovers. But an Internet search revealed something more intriguing. According to waymaking.com, Horace and Libby Rockwell operated an Overland Stage Station here from 1866 to 1900. Horace, the brother of the famous Mormon avenger Porter Rockwell, and his wife Libby could not have children so Libby filled the void with pet dogs and cats who were buried here. It was deathly quiet. I can't imagine what spending 34 years here would do to a person's psyche.

At the nearby Simpson Springs Pony Express station, where riders stopped for supplies and fresh horses while delivering mail from the East to West coasts from 1860-61, delicate purple flowers dotted the desert floor. Only a crow's occasional cawing broke the silence.

Lynn Drollinger of Stansbury Park, out for a spring drive, told us 46 wild horses walked in front of his car a few days earlier not far from that spot.

"Tooele is not a big vacation destination," he joked. "But if you come here, there are some great things to see if you know where to look."

As we headed west to Callao, the snow-covered Deep Creek Mountains came into view. The people who named such West Desert ranges as the Deep Creeks, Confusions, House, Silver Island, Pilot Peak, Muddy and Newfoundlands did themselves proud. They describe the place well.

It wasn't long before we hit pavement, our hips and vehicles happy to leave the bumpy, dusty trail. Approaching Wendover, where we spent the night, the garish lights of casinos adjacent to old airfield where soldiers trained to drop the first atomic bombs on Japan seemed almost natural. A visitor to this land quickly learns not to be surprised by anything.

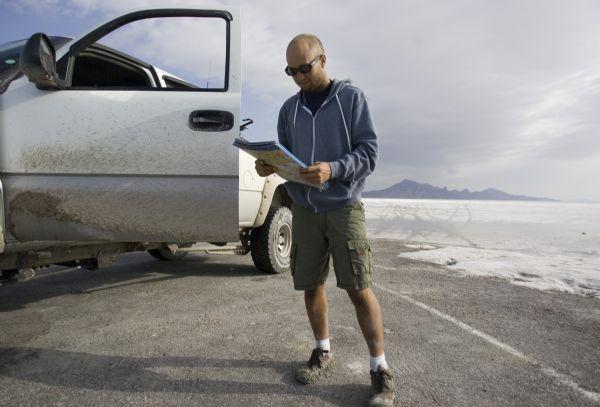

Early the next morning, we gassed up our trucks and made a brief stop at the Bonneville Salt Flats, where Scott McCann of Spokane, Wash., was using a snowboard to dig his four-wheel drive truck out of the muck. He had stopped to take a photo and the big rig's tires broke through the salty crust into the smelly mud.

"I always wanted to check out the Bonneville Salt Flats," he said. "This was a photo op, but then I tried to leave and got an even better photo opportunity."

We began driving north on a road where the pavement turned to dirt, and stopped to explore interpretive signs along the California Trail. One side road led to Hall's Spring near Hasting's cutoff, a route used by western settlers heading to California. A peregrine falcon flushed. Near one interpretive sign, a pair of white iPod headphones lay on the ground.

Heading north towards the Lucin ghost town, we encountered more strange sights.

A large chunk of unfenced desert was empty but for a "for sale" sign. Soon after, a city street sign told us we had reached the corner of Mission Ranch and Pilot Mountain roads. A tattered piece of American flag, flopped in the wind above a sign that read "Jesus Lives."

Under a threatening sky, we had to look hard for the Sun Tunnels, created by artist Nancy Holt in 1976. The four concrete tubes, 9 feet wide and 18 feet long, are placed in an "x" on a bare piece of desert. Holes cut into the concrete correspond to celestial constellations of Perseus, Draco, Columba and Capricorn. It looked like some daredevil had raced a motorcycle around the tunnels because tire treads could be seen on the inside. Tribune photographer Jimmy Urquhart wondered whether bullets might have made the marks.

The tunnels are near now-abandoned Lucin, where trains once stopped to get water and which was named after a local fossil bivalve. Tall, gnarled trees shaded an inviting pond where the silence was broken only by the drip of water from a spring until two freight trains roared past, their horns blasting.

We hit pavement on Utah 30, 42 miles from Park Valley, then left it again to stop at the Kelton ghost town. The cemetery, with graves dating back to the 1870s, is in a glorious state of disrepair: The wooden headstones are nearly gone and many of the stone ones are so weathered they can't be read.

It would have made a fitting final stop to our desert journey had we not lost our way when we tried to drive across the old transcontinental railroad bed and ended up at a locked gate at Locomotive Springs. Using maps, Jimmy's GPS and some advice from strangers in the one vehicle we saw, we managed to find Golden Spike National Historic Site and left dirt for the last time.

We said goodbye to the empty desert wide open spaces to return reluctantly to freeways and traffic jams.