This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Utah's Nobel-winning geneticist Mario Capecchi has determined bone marrow abnormalities cause compulsive behavior in mice, results that could point to novel ways to treat psychiatric illnesses with immune-based therapies.

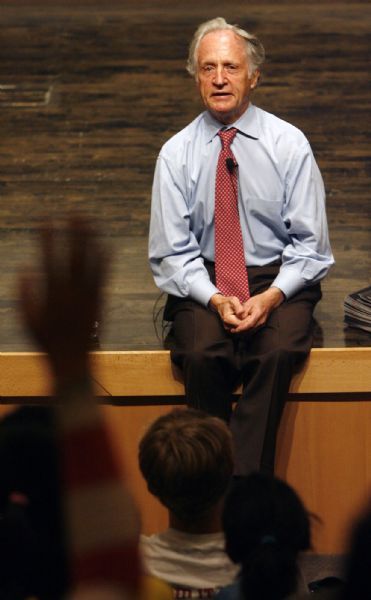

"It puts a direct connection between the immune system and behavior. We know a lot more about the immune system than the brain. The brain is a black box. How it works, we don't really know," said Capecchi, a University of Utah professor of human genetics. He shared a 2007 Nobel Prize for his work in gene targeting, a process that allows researchers turn off specific genes in mice.

For years, researchers have observed correlations between various mental illnesses and immunological disorders in people, but didn't know what was causing what. Did the mental illness arise in response to a disabling auto-immune problem? Or do psychiatric problems and therapies suppress the immune system?

In a study published in today's edition of the journal Cell , Capecchi and his U. colleagues establish show that a mutant version of the gene Hoxb8 disturbs marrow, the pliable blood-producing tissue inside bones.

A 2002 study by Capecchi connected this gene with pathological hair pulling and self-mutilation in mice. Capecchi has now shown the gene causes the production of defective microglia, immune-system cells produced in bone marrow that migrate to the brain. Most microglia are with the brain at birth, but 40 percent originate in the marrow as white blood cells. It's the migratory microglia that Capecchi's team studied.

Microglia were once thought to be the brain's "scavengers," cleaning up dead tissue following neurological injury, he said. But they now appear to serve an immunological role, defending the brain and spinal cord against infection.

Capecchi's new study describes how the team induced pathological fur grooming by transplanting this mutant marrow into healthy mice, then cured them by transplanting normal marrow.

"It was a surprise, but it worked. We can do it both ways," Capecchi said.

The condition is akin to trichotillomania (trick-o-til-o-MAY-nee-ah) in humans, which affects about 2 percent of the population. Capecchi believes the hair-pulling disorder in mice is a good model for human obsessive-compulsive disorders, but some neuroscientists aren't so sure.

"I am skeptical of animal models of 'obsessive compulsive disorder,' which requires senseless behaviors (including hand washing) with insight that they are irrational," wrote Judith Rapoport, a branch chief in child psychiatry at the National Institute of Mental Health, in an e-mail. "Very tough to get [an] animal model."

The U. results disprove previous theories that the hair-pulling disorder is cause by decreased sensitivity to pain, said Capecchi, who is also an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which funded the work along with the National Institutes of Health.

Capecchi stressed he does not propose treating mental illness with bone-marrow transplants, which are costly and dangerous, and normally reserved for life-threatening cancers and auto-immune disorders. But the research could point to new explorations of immune-based treatments.

The next step is to determine what defective microglia do to the brain.

"How does is it affect behavior? My guess is there can be multiple ways, but that will take us a few years," Capecchi said. "We anticipate it has to affect neural circuitry in some way."

Capecchi's co-authors included geneticist Shau-Kwaun Chen; postdoctoral fellows Petr Tvrdik, Erik Peden and Sen Wu; Gerald Spangrude, an internal medicine professor; and Scott Cho, a graduate student in Spangrude's lab.