This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Recruiters wouldn't leave Simi Fili alone.

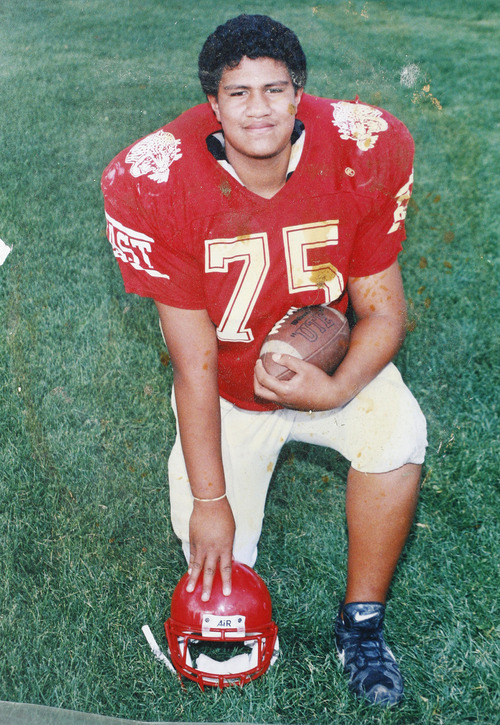

In 2007, the star defensive lineman at Cottonwood High School toyed with scholarship offers from the University of Oregon, University of Utah and Washington State. He chose the Oregon Ducks while flashing a baseball cap bearing the school's logo in the middle of the nationally televised U.S. Army All-American Bowl, fueling Utah's excitement over the possibility of another homegrown future NFL star.

While Fili's life on the surface seemed on the fast track, few knew of challenges behind the scenes of his athletic accomplishments.

As the 17-year-old entertained calls from coaches promising him glory on the college football field, another set of recruiters never had their sights set far from him: The Tongan Crip Gang.

Friends and family with gang ties in Fili's Glendale neighborhood were always in the periphery of his world, offering temptation. Did Fili want to accompany them to make a beer run at a convenience store? Did Fili want to go to a party where drugs were readily available?

For Fili, an ongoing choice has defined his young life — to join the gang his uncle helped build into a criminal enterprise or to take the path of a life outside violence.

"I probably could be the next big gangster out there," said Fili, now 22. "I could use my uncle's reputation. He started it, and now, I'm next."

"But gang life is easy to do. Pulling out a gun and shooting somebody? Anyone can do that. It's so hard for someone to go to school and stay focused."

The latter road for Fili hasn't come without speed bumps.

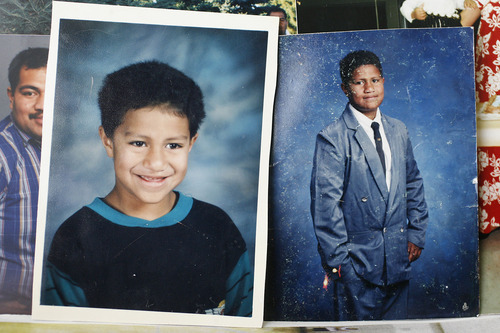

Uncle Miles • Fili was in elementary school the first time he saw his uncle, Maile "Miles" Kinikini, shackled in handcuffs and dressed in a jail jumpsuit in a Salt Lake City courtroom.

Just a child, Fili didn't understand why his mom and aunt dabbed away tears as a bailiff led Kinikini away.

Kinikini, who calls himself one of TCG's "original gangsters" in Salt Lake City, also remembers his young nephew watching his every move. Now, 37, he regrets the example he set.

Kinikini discovered TCG in the mid-1980s when as a 9-year-old, Latino kids in his west side neighborhood picked on him as he walked to school. He let an older group of Polynesian boys beat him up in exchange for protection, and in the ritual, known as being "jumped in," Kinikini found comrades with whom he'd carry out drive-by shootings and sell drugs to earn money.

Kinikini, who went by the moniker of "Mr. C" — the "C" standing for both "criminal" and "Crip" — moved up the ranks of the gang to become a shot caller. He brought Utah's escalating gang problem to the forefront when on July 23, 1992, he opened fire on rival gang members in the middle of State Street, near crowds of people staking out spots for the next day's Days of '47 Parade.

TCG had killed three members of a rival Samoan gang and the rival gang wanted revenge. That showdown led to the State Street incident in which Kinikini shot his .357 pistol into the vehicles of his rivals.

Two passengers were wounded, but no one died, Kinikini said. Drunk after downing a fifth of Black Velvet whiskey and high on acid when he fired, the crime landed Kinikini behind bars.

That's when he found religion.

"The boys I was running with, I'd take a bullet for. When I was locked up, none of them came to visit me," Kinikini said. "I know it sounds like a cliche, but I picked up the Book of Mormon. Finally, the pieces started to fall in."

After his release, he served a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Northern California in 1994. He said at that point he left TCG, avoiding repercussions — such as getting killed for doing so — because of his high rank as a gang leader. Kinikini married and celebrated the birth of his first child.

He returned to Glendale and started telling youth to avoid gangs, in particular Fili and his other nephews. He ordered TCG members to stay away from Fili, a command that had credence because of Kinikini's street credibility, he said.

But the gang's pull drew Kinikini back into crime on Oct.17, 1998. That day Kinikini's aunt told him members of another gang had shot a car in front of her house, barely missed a baby inside.

Kinikini tracked down the perpetrators then firebombed their home, burning it to the ground with gasoline-filled plastic milk jugs.

An arson conviction earned him another year in jail.

"I let the community down," Kinikini said. "I was every parent's savior (for telling their kids not to join gangs). Then I turned around and blew up the house."

Opportunities away from Glendale • Fili watched the dramatic events in his uncle's life unfold as TCG started playing a growing role in his own daily routine.

As Fili grew older, pieces of the dark part of his family's history became more clear. As a third-grader in Glendale, Fili noticed scribbling around school for Latino gangs like "SUR 13" and "QVO." Unsure of the significance, Fili started writing gang graffiti on his notebooks to fit in. Copying the Latino kids didn't last long.

"You'd go into the bathroom stalls and you'd see QVO this and that. I started writing down some of that stuff," said Fili. "One day someone told me, 'That's a Mexican gang.' You've got to write TCG."

The gang's influence stretched to Fili as he watched friends congregate with older members of TCG. At respite couldn't be found at the neighborhood Boys and Girls Club, where the same kids Fili tried to avoid on the streets used the center as a place to meet up instead of a place for recreation, he said.

Fili tried to listen to his uncle's advice, yet the gang's influence was never far away.

"Sometimes we'd wake up to gunfighting. A lot of people don't think Utah is like that," Fili said. "That's the problem. People don't understand. We have the same problems as Los Angeles and New York."

Wanting to keep Fili away from the wrong crowd, his mother, Le'o, transferred him to Bryant Junior High School in Salt Lake City's more affluent Avenues neighborhood.

From there, Fili earned a scholarship to the private Juan Diego Catholic High School in Draper before the daily 40-mile commute from Glendale each day prompted his parents to move him closer to Highland High. He moved again to Bonneville Junior High School in the Granite School District, where as a ninth-grader he made different friends from the elementary school classmates who were falling deeper into TCG.

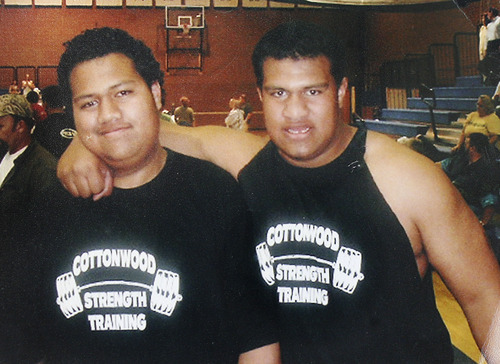

A talented athlete, the 6-foot-4, 325-pound, Fili struggled in the classroom. Encouraged by Cottonwood High's reputation for tutors and other amenities provided by a wealthy booster, Le'o Fili believed she'd found a school where her son could focus on academics, develop his athletic ability and stay free from gangs.

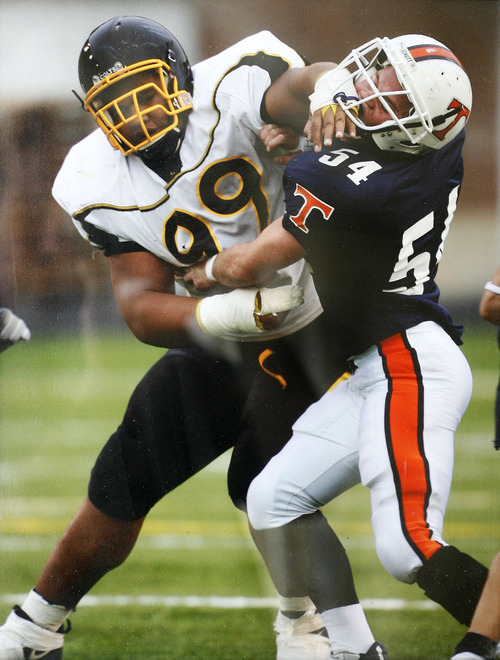

He found success with the Cottonwood Colts, establishing himself as one of the state's up and coming recruits. He also watched former friends from the neighborhood at East High play football by day and hang out with the gang at night.

"A lot of the kids my age were affiliated with the Tongan Crip Gang. They'd go play football and would go into gang banging and all that crazy stuff right after," Fili said.

His choice of football over TCG wasn't forgotten in the neighborhood. At a game where Cottonwood played East High, the event had a deeper meaning than a football score, Fili said. TCG members pounded him on the field, a chance to take an extra dig for Fili's decision to avoid TCG for what he saw as a brighter future at Cottonwood.

Cotttonwood lost the game.

"They hated us. We didn't affiliate with them and we didn't hang out with them," Fili said, referring to himself and others who chose not to join TCG. "We kind of just went our own way. In that sense in the neighborhood, when you don't hang out, they wonder about you."

Fili fought through the trials of attending school in one city, then navigating a sometimes unfriendly neighborhood in another. He nabbed a scholarship to the University of Oregon in 2007. He chose the Ducks after a recruiting trip where he felt like royalty, he said, being driven around in a golf cart where he fell in love with Eugene's scenic campus and plush athletic facilities.

But the opportunity was short lived when he failed to meet NCAA regulations and academic standards.

"I tried to tell him, 'Simi, you need to focus on your grades,' " Le'o Fili recalled. "He wouldn't listen.

Another chance • The missed chance was a blow to Fili, who thought his dreams of playing professional football were over. Then, junior colleges started calling.

But the junior college experience found Fili swimming in more academic problems. He attended Eastern Arizona in Thatcher, Ariz., a short-lived experiment after homesickness and disappointment over not attending a Division 1 school drove him back to Utah. He returned to Salt Lake Community College for one semester. Next was a stint at Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, Calif., where he lived out of his truck for awhile. Then it was back to Arizona, at a community college in Mesa, where he took a part-time job as a bouncer after discovering his scholarship didn't cover many expenses.

Fed up with failure, Fili decided to ditch football and school and followed a friend to California. He enrolled in acting classes and thought about a career as a bodyguard.

A transient lifestyle eventually led him back to Salt Lake — where old friends active in TCG still had room for him in the gang life.

Fili's uncle, Kaisa Kinikini, quickly spotted trouble brewing. He saw Fili driving around with friends in what he suspected could have been stolen vehicles. He knew Fili was at parties with people connected to TCG.

"He was starting to go around with gangster kids, everyone he grew up with," said Kaisa Kinikini. "He went to those who accepted him."

Kaisa Kinikini, a former gang member and Miles Kinikini's cousin, founded the anti-gang Stand a Little Taller or S.A.L.T program in Glendale.

Kaisa Kinikini started S.A.L.T in 1999 in the form of a football program, which grew into what is now a team called the Stripling Warriorz. Most of the team's players are plucked from Glendale and are at risk for gang involvement or are trying to leave their respective gangs. The nonprofit program also helps young people find education opportunities, employment, mentoring, and activities, such as the Warriorz.

Kaisa Kinikini thought if he could renew his nephew's love for football, he could keep him from the grips of TCG. So he started bugging Fili daily, stopping by his house and repeatedly calling him. He wore him down.

Fili soon became a mentor to others on the team who admired the big man's techniques and skill on the field.

In the process, he rediscovered his ambition.

"Uncle Kaisa gave me that extra push," Fili said. "I didn't see the big picture. I always thought 'me, me, me.' When I was helping kids it was finally, 'OK, I'm going to help you out.' "

A second chance • Content living in Salt Lake City and helping out with Kaisa Kinikini's program, Fili was skeptical when a football coach from East Central Community College in Decatur, Miss., called him last fall.

"I told him, 'I'm done with football. I'm going to be an actor,' " Fili said. "Coach told me, you're going to regret this. You're going to grow up old and gray and wish you hadn't given up football. He had a point there."

Fili arrived this spring in Decatur, where his tuition is paid in full. He receives a housing and a food stipend. Life in the south, in a town that has just one stoplight, is an adjustment, he admits. But people in Decatur are friendly and anxious to see the guy they call "the big Hawaiian" on the football field.

When he's out for training runs, folks roll down their windows and shout "I hope y'all do good this year," Fili said. He said he has also learned from past classroom mistakes and is better prepared to hit the books.

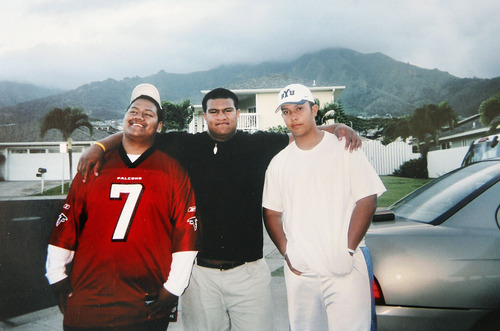

While Fili's life moves ahead, he looks back on photos of his Little League football team in Glendale with sadness. In many of the photos is a disheartening contrast: one half of the picture is Fili and his cousin, Stanley Havili, who went on to become a standout football player at the University of Southern California. On the other side are childhood friends who made different choices.

He knows the majority of 17 suspects indicted in a racketeering (RICO) case filed in U.S. District Court last year against high-ranking members of TCG. Fili also weathered the murder of his cousin, and Filikisi "Junior" Hafoka .The 23-year-old was killed in prison last year, while serving a 12-year sentence at a federal penitentiary in Jonesville, Va., for his role in a robbery that was carried out with several TCG members, resulting in a 7-Eleven clerk being shot in July 2007.

"I knew these boys," said Fili, who attended Hafoka's funeral. "They could do things with their lives. When I hear this kind of stuff, I tear up."

Fili credits his parents for helping him make the right decisions, while Miles Kinikini applauds his nephew for not ending up at part of the recent RICO case.

"It's tough to grow up in this," he said of Glendale's gang culture. "Simi had it pretty hard. I'm proud of him that he made good choices."

Fili said he's motivated to graduate college and dreams of following in the footsteps of his cousin, Haloti Ngata, who played at Oregon before getting selected by the Baltimore Ravens in the 2006 NFL draft. He'd love to make it in the big time in part to help fund anti-gang initiatives in Salt Lake City, including the S.A.L.T. program.

Fili says he doesn't want to see other kids throw away the chance he once had, almost lost, but has since regained.

"The thing I'd like to tell the younger kids," Fili said, "is there is more to life out there than gang life."

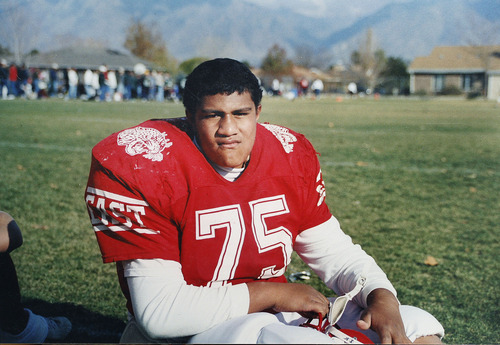

Simi Fili's promising high school football career

As a senior defensive lineman at Cottonwood High School in 2007, Simi Fili attracted national attention for his football skills. He committed to play at the University of Oregon during the U.S. Army All-American Bowl in January, when a television camera filmed him wearing a Ducks hat during a break in the nationally televised game.

Fili picked Oregon over Washington State and Utah.

He was considered the state's top prospect by several recruiting services. Had he attended Oregon, he would have followed in the footsteps of his cousin, Haloti Ngata, who played at the school before getting selected by the Baltimore Ravens in the 2006 NFL draft. Another one of Fili's cousins and fellow Cottonwood graduate Stanley Havili became a standout at the University of Southern California and is a prospect in the 2011 NFL draft.

Academic missteps kept Fili from competing at Oregon. He attended four community colleges before landing a scholarship at East Central Community College in Decatur, Miss., where he is gearing up for the 2011 football season.

Fili said he is hopeful he may regain scholarship offers from Division 1 football programs after his first year in Mississippi, before he has used up all of his NCAA eligibility.