This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's Note: This is part one of a two-part series on the making of a Utah political icon —six-term U.S. Senator Orrin Hatch. Read part two at http://bit.ly/xoLtPB.

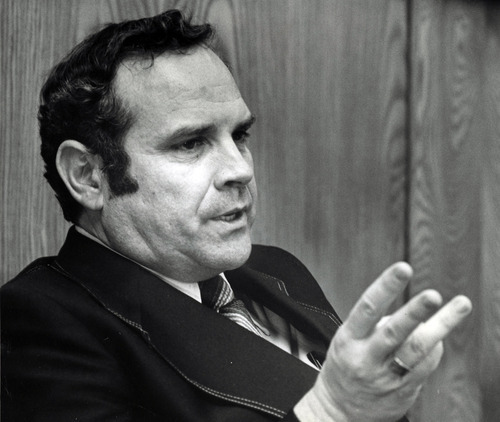

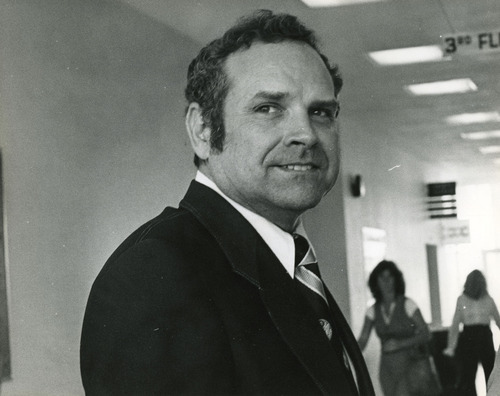

Washington • One by one, Orrin Hatch told his closest friends and family that he would run for the Senate and their reaction was nearly universal: He had no political experience and therefore no chance.

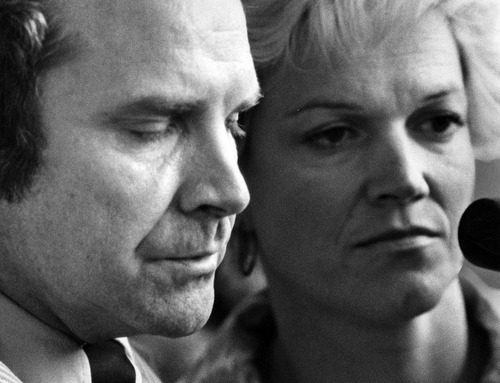

His wife's response was no more encouraging. She cried for three days.

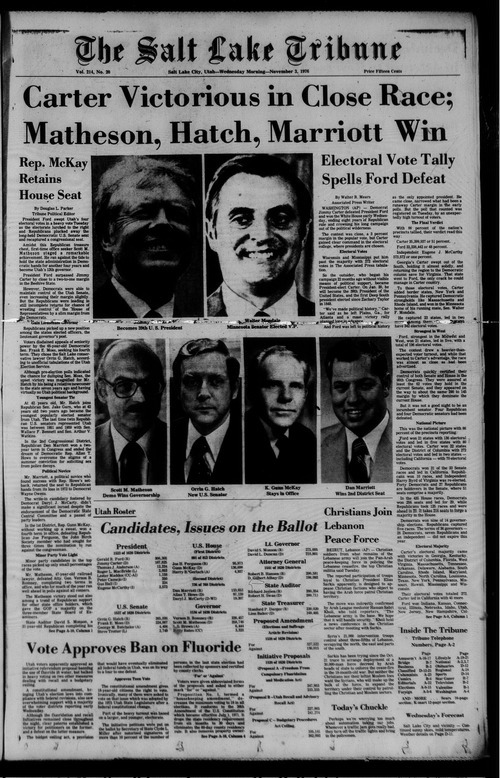

The year was 1976, and you know how this story ends. Hatch defeats Sen. Frank Moss, launching a political career unparalleled in the state of Utah. But how he claimed that first victory is a story worth telling. The rise of Sen. Orrin Hatch involved nothing short of a sex scandal, a surprise endorsement and a political shift of historic proportions.

Now, 36 years later, he faces what is likely his last electoral showdown against two upstart Republicans who want to duplicate his feat and best a powerful incumbent.

They'll have the assistance of a political climate similar to the late 1970s, with a nation in economic turmoil and voters harboring a throw-the-bums-out mentality. The challengers — Dan Liljenquist and state Rep. Chris Herrod — are expected to run a campaign similar to that of a young Hatch, portraying themselves as Washington outsiders intent on reducing the scope of the federal government.

But as Hatch's first race shows, winning an election often hinges on a few big decisions and some factors out of a candidate's control.

'Nobody knows you' • He had his own law firm and served as the bishop of his LDS ward, but Hatch had not participated in politics since moving to Utah from Pittsburgh in 1969.

His friends didn't know he entertained the possibility of running for office until he broke the news just weeks before he would launch his campaign.

"I said: 'Nobody knows you, you have no money. It's impossible,' " recalls Frank Madsen, who was the bishop before Hatch. "And he said: 'Well, I'm going to do it and I can win.' "

Walt Plumb, his partner in the law firm, also tried to talk Hatch out of it, but their conversation turned from the logistical challenges to Hatch's motivation.

"He felt like God wanted him to run for the United States Senate," Plumb said. "That's how he felt. Definitely."

Hatch doesn't describe it that way, but he also doesn't deny a spiritual impulse.

"I don't claim that I was chosen by God to run for the United State Senate, nor do I think anyone else should claim that," he said. "But I knew it was the right thing to do."

Hatch, then 42, filed for office on the last possible day, just a week before Utah Republicans would hold small meetings to elect delegates for the state convention.

He said his knees buckled when he finished the paperwork and faced the media. The story in the next day's edition of The Salt Lake Tribune was the first time he was ever mentioned in the newspaper.

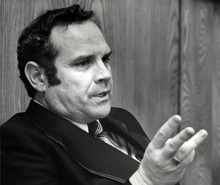

He described himself as a "nonpolitician" and said: "The old-line party professionals tell me I have no chance to win — to even come out of the party state convention. But I'm used to impossible odds. That's the story of my life."

To gain his party's nomination, Hatch would have to best four GOP candidates who had been campaigning for months. The group was led by Jack Carlson, who resigned his post as assistant Interior secretary in the Ford administration to return to Utah to campaign. The others were Sherm Lloyd, a former Utah congressman; Des Barker, who had worked in the Nixon administration; and Clinton Miller, a former lobbyist.

Courting the right • In those early days, Hatch's support came largely from people with ties to Pittsburgh. That includes Mac Haddow, who grew up near Hatch's parents, Jesse and Helen, and considered them surrogate parents.

Haddow was a 25-year-old Brigham Young University student volunteering on the campaign when Hatch entered the race. A few weeks later, Hatch asked him to lead his entire campaign.

Like Hatch, Haddow was a political novice, but aggressive and relentless. The campaign moved into a dumpy house on Salt Lake City's 400 South, and Haddow often slept there.

Beyond Haddow, 69 former missionaries who served in Pittsburgh became state delegates and others talked up Hatch to their friends. Among them was Gov. Gary Herbert, who met Hatch on his mission in 1969.

Hatch ran to the right of his four competitors, seeking the support of the most conservative factions in the state at a time when the far right held little influence.

Two of his most prominent backers were Cleon Skousen and Ernest Wilkinson.

Skousen, a former FBI agent and ex-Salt Lake City police chief, was seen as an influential figure for the John Birch Society. He provided early financing and volunteers, though the Hatch campaign tried to keep him at a distance, fearing that being seen as too close to Skousen would alienate other voters.

But the campaign fully embraced Wilkinson, who was the president of BYU and a former Senate candidate himself, though he lost to Moss in 1964.

The support of Skousen and Wilkinson jumpstarted Hatch's campaign and gave him some early legitimacy.

"He hit a chord with the conservative movement," said Plumb. "That group was absolutely fanatical."

—

Gaining steam • The other GOP candidates were not impressed. It wasn't just that they dismissed him as a fringe candidate, they also didn't think he had time to catch up. Hatch tried the traditional route of knocking on doors and holding small meetings, but his opponents had spent months recruiting volunteers, raising money and reaching out to likely delegates.

His campaign knew it had to get creative and turned to the cutting edge technology of the time — the cassette tape.

Hatch had all the necessary equipment because he had a small side business where he created legal and religious tapes, making it easy for him to mass-produce a 12-minute recording and mail it to each of the 2,500 delegates. He also sent a printed version for people who did not own a tape player.

"It was shocking the number of delegates who loved them," Haddow said. "He didn't have to knock on doors or see them physically, he actually got into their homes with technology."

On the tape, Hatch tells his life story, outlines his policy differences with Moss and makes a direct plea to delegates to help him get into a primary, while taking shots at his opponents for their ties to Washington.

"They believe they have the convention delegates all locked up. I don't believe that," Hatch said on the tape. "Please consider voting for me; then the Republicans will have a real choice."

On convention day, Carlson clearly had the momentum and the most sophisticated campaign operation, but Hatch's attention-grabbing moves were starting to pay off. While recognizing that he was gaining steam, Carlson's camp looked at the man and his campaign as an oddity more than a threat.

Carlson's wife, Renee, wrote a short retrospective on the campaign titled "The Best Man Doesn't Always Win," in which she describes observing Hatch as he mingled with delegates.

"Orrin was tall, physically attractive, however, and aware of this in an almost sensual way. Sometimes he seemed vain and egocentric; other times he displayed a forced testimony-bearing humility that left me either awed or disgusted," she wrote. "His rhetoric seemed to appeal to those who were slightly estranged from the general society."

Some Carlson advisers wanted a primary race against Hatch and, at the end of the convention, they got what they wanted.

Carlson received 930 votes, Hatch took 778 — assuring a two-man battle for the right to challenge the third-highest-ranking Democrat in the land.

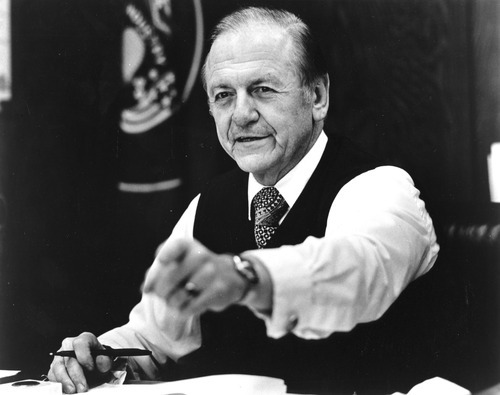

'Well-spoken bureaucrat' • Carlson, who died of a heart attack in 1992, was an Air Force fighter pilot and Harvard-educated economist. He worked for Republican presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford before he moved back to Utah to run for the Senate.

He was a federal budget expert with a deep understanding of energy issues who, with the help of Sen. Jake Garn, R-Utah, campaigned as the establishment candidate.

But he ran at a time when voters were unhappy with the establishment. The Watergate scandal still hung over politics and the economy was struggling.

Hatch's campaign wanted to turn what Carlson saw as his strengths into his weaknesses.

"Carlson was a very fluent, well-spoken bureaucrat. That is what he was, so we painted him that way," Haddow said.

On the flip side, Carlson tried to attack Hatch as being unprepared for the job and looked on with amazement when voters seemed to respond to Hatch's call for deep spending cuts and a constitutional amendment to balance the federal budget. Carlson considered such moves extreme, and his wife documented their growing resentment.

"We were running against someone whose fundamental opinions and philosophy scared us and could undermine the very democracy we had sworn to defend," she wrote.

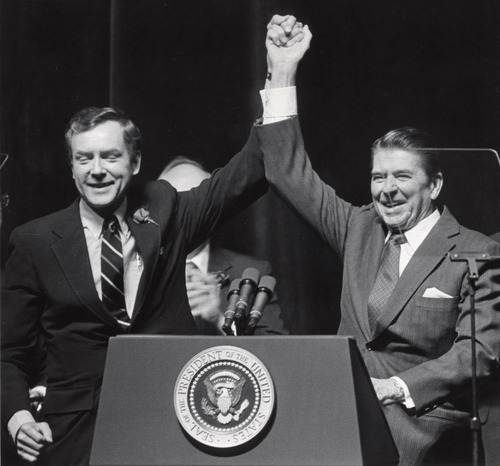

What they didn't know at the time was that they were also running against a national heavyweight — Ronald Reagan.

Last-minute intervention • With just days to the primary, a poll showed Hatch behind Carlson but in striking distance. Haddow wanted Hatch, an early and active supporter of Reagan, to ask for the famous California governor's endorsement, but other advisers wanted to leave Reagan alone only weeks from his painful defeat in the GOP nomination battle with Ford.

After a few days of debate, Hatch decided to go for it. He got in contact with Reagan's point man Mike Deaver, who in turn talked to Reagan's pollster Dick Wirthlin, a Mormon with deep Utah ties. Wirthlin thought Hatch had a chance to win.

Reagan agreed to back Hatch, but since he was out of the country, it would have to be through a telegram. Hatch's campaign immediately called a news conference and the telegram arrived with only an hour to spare.

But there was a problem. It endorsed Warren Hatch, not Orrin Hatch.

They didn't have time to correct the flub, so Haddow doctored the telegram to make it look as if it said "Orrin" and went ahead with the announcement.

Carlson's team heard about the mistake and challenged the authenticity of Reagan's support, which resulted in a KSL-TV story with Haddow acknowledging the misspelling.

To rectify the problem, Reagan called in to a KSL news show on Saturday evening and endorsed Hatch again.

Carlson tried to counter with a Ford endorsement, but the president's staff didn't want to interfere with a party primary.

Hatch didn't just beat Carlson that Tuesday. He crushed him, claiming 65 percent of the vote.

Hatch says he would have won with or without Reagan's help, but Carlson didn't see it that way.

"We tried our best," he said, "and I think we would have won without this last-minute intervention."

Out of the blue • Hatch's victory surprised Sen. Frank Moss and his supporters, who had spent months preparing to face Carlson.

"Hatch was just out of the blue as far as we were concerned," said Brian Moss, the senator's son, who left a job in Washington to lead his father's re-election effort. "Nobody knew him, really."

While the GOP was selecting a nominee, Moss did little campaigning; instead, he stayed in Washington, gaining national attention for uncovering Medicaid fraud. But some of the headlines were less to the campaign's liking. One of his protégés was consumed in scandal.

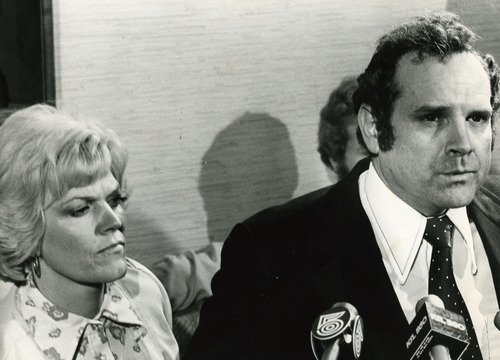

In June, Rep. Allan Howe, who previously served as Moss' chief of staff, left a Democratic gathering in Salt Lake City and tried to pick up two prostitutes, offering to pay $20. They were undercover police officers.

The day after his arrest made national headlines, Howe met at Moss' D.C. home, where the senator urged him to resign.

Howe initially agreed, but when he heard the police had no recording of his interaction with the undercover officers, he decided to fight the charges and run for re-election.

A court found him guilty at the end of July. He appealed and was convicted again in late August, in a painfully public trial, the political impact of which is still up for debate.

Utah pollster Ray Briscoe told the news outlet UPI that Howe was costing Democrats 4 to 6 percentage points. And Brian Moss believes the Howe scandal wounded his father's campaign significantly.

"We lost Salt Lake. How does a Democrat survive losing Salt Lake?" he said. "It was because of Allan Howe."

Brian Moss, who also ran against Hatch in 1988, said his father downplayed the Howe effect and so does Haddow, who noted that Scott Matheson, a Democrat, became governor that year.

But one thing that clearly had an impact was a political metamorphosis that turned centrist Utah into one of the most Republican states in the nation, according to Jay Logan Rogers, who wrote his master's thesis at the University of Utah on Hatch's first campaign.

In part, the switch was driven by LDS opposition to abortion, the Equal Rights Amendment and labor laws, issues that Hatch hammered in the election. Hatch portrayed himself as supporting Mormon values, including a deep skepticism of the federal government.

Utah's rightward swing picked up steam in the years to come with the Reagan Republicans, the gay-rights debate and the rise of hyperpartisanship.

Hatch was on the vanguard of a Republican wave, and what Moss thought would be an easy victory turned into a fight he was unprepared to wage.

"I just remember that suddenly September was on us and it was more of a reactive campaign," Brian Moss said.

Moss' campaign was slow to hit back at Hatch's jabs that the incumbent was a liberal out of step with Utahns, but eventually launched ads labeling Hatch an opportunist, a right-wing extremist and a carpetbagger since he moved to Utah only seven years prior.

Just like Carlson, Moss was ill-equipped to debate Hatch, who excelled at public speaking and on television.

Brian Moss said his father could have survived two obstacles, but he faced three: the Howe scandal, the conservative wave in Utah and an aggressive, TV-ready opponent.

And yet, it wasn't until Election Night that Moss realized he would go down in defeat. Hatch claimed 54 percent of the vote in a victory that caught the eye of political observers nationwide and would launch a career that continues to this day.

mcanham@sltrib.com

Twitter: @mattcanham