This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Real estate developer Steve Pruitt hardly seems like a guy with the kind of engineering credentials to revolutionize one of America's most important industries.

But the Salt Lake City man's successful hobby building a Le Mans-style hybrid racing car has led to two technology breakthroughs, which he believes can revolutionize the diesel engine and long-haul truck business.

Pruitt's three-employee company has developed prototypes designed to dramatically reduce diesel emissions, improve fuel economy and make big rigs safer. Diesel engines powering heavy trucks transport 78 percent of all goods moving across the United States.

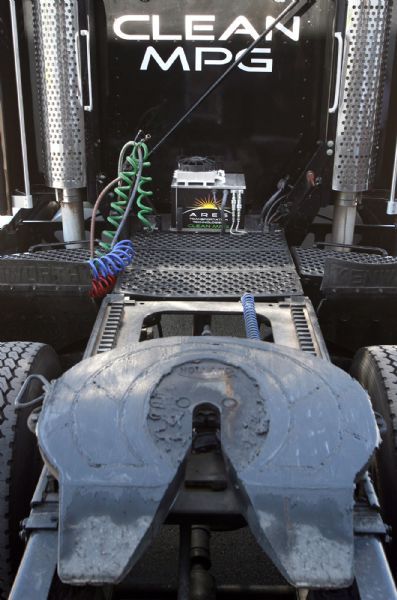

"Our first goal is safety, our second reliability and the third performance," said Pruitt, who uses, as a test vehicle, a semi-trailer and tractor emblazoned with the motto "Rocket Science for the Road."

"Racing gives you an engineering degree without having an engineering degree," said Pruit, whose 1,900-pound 700-horsepower hybrid race car can reach speeds of 220 mph. "Racers are resourceful people."

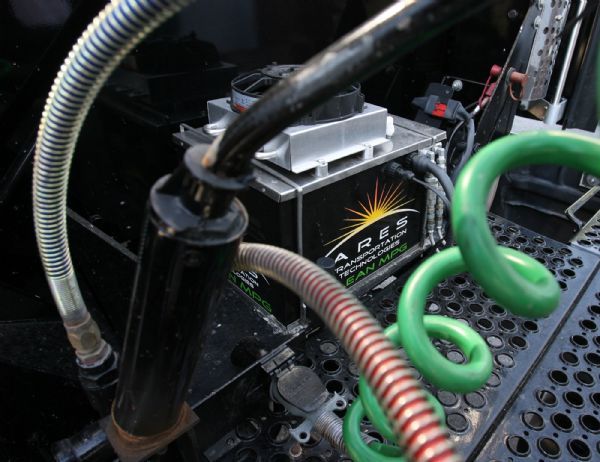

Under the name ARES Transportation Technologies, the fledgling company hopes to manufacture and install its Clean MPG and KERS Assistive Drive Technology devices. Both are generating interest among federal, state and local officials from the Department of Energy, Environmental Protection Agency and government fleet managers.

He has a meeting scheduled for Tuesday

with Salt Lake County Mayor Peter Corroon to see if the county diesel fleet might be interested in the technology. Another meeting is scheduled with the fleet manager for the campus shuttle system at the University of Utah.

Pruitt likes the U.'s involvement because he wants its Institute for Clean and Secure Energy to test emissions reduction and get real-life mileage data from the shuttles.

He said that he could have the devices installed within 30 days by outsourcing manufacturing to other companies, preferably in Utah.

A grant from the governor's Utah Science Technology and Research Initiative helped fund initial development.

The Clean MPG device enhances diesel combustion. Hydrogen is used to increase the flame-spread rate, and this serves as a combustion acceleration. According to Pruitt, the device requires only a small, easy-to-install one-half-inch gas port, three wires, two hoses and a gallon of distilled water.

The other system is called the ARES KERS Assistive Drive Technology. It works a bit like a hybrid car's regeneration system. It features two electric motors which are powered by a kinetic energy-recovery system. The idea is to capture the trailer's momentum when it slows or brakes and store that energy in batteries to power the electric motors.

Benefits include a reduction on brake wear, and the batteries can be used as an auxiliary power source when the rig is parked. This could reduce, if not eliminate, idling that burns 2,200 gallons of fuel annually for the average tractor.

The company uses a 1996 T600 Kenworth truck pulling a 53-foot, generator-equipped trailer to test its systems. Pruitt said mileage was improved by 18 percent to 22 percent. Fuel consumption in the generator dropped by 18 percent.

So the question is will such a system work on a big fleet?

Salt Lake County Fleet Manager John Webster said he is interested, though he thinks it might have better application for long-haul trucks than for the sanitation trucks in his fleet.

"I find it extremely interesting when you are trying to keep your costs down," he said. "If you can raise your fuel economy by 10 percent but are breaking down all the time and need more trucks to back up the down trucks, that could be a line that shouldn't be crossed."

Pruitt estimates that using the technology has the potential to save Salt Lake County's fleet $2 million a year in fuel costs and the Utah Transit Authority buses $4 million.

One guy who appeared to be interested was Washington state truck driver George Catlin, who joined dozens of other drivers idling their trucks in a hot day at a Salt Lake City truck stop. He said anything that can save and meet increasingly stringent emissions requirements "sounded good" to him.