This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Kaleb Winston followed two police officers who called him out of the West High School cafeteria last month, unsure of why he was being led to a school security office.

He soon found out.

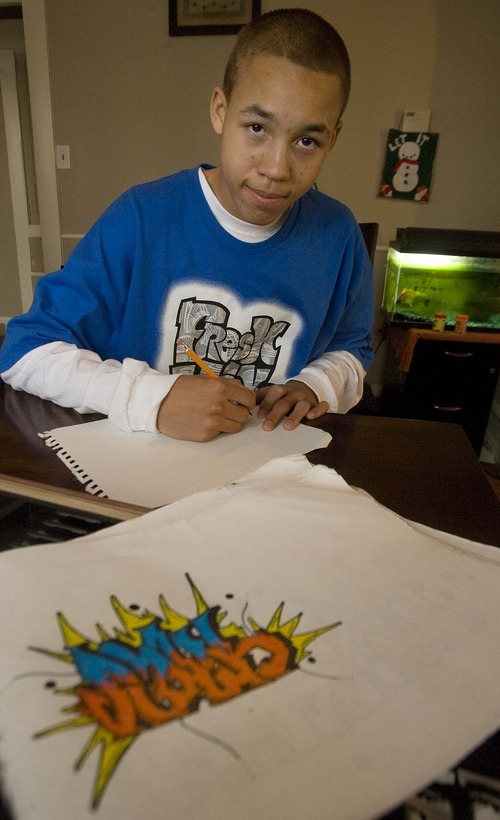

"Are you in a gang?" the officers asked, questioning him about a graffiti-patterned backpack that his parents bought him at Shopko before school started in the fall. They also pulled out a sketch pad from his art class, pointing to assignments they claimed resembled gang insignia.

Surprised, the 14-year-old denied gang connections.

Officers didn't buy his story, telling the boy they had received information from a teacher that he had been tagging the moniker "Maze" around school.

They photographed the boy holding a plate, reminiscent of what suspects hold while being booked into jail. It read, "My name is Kaleb Winston and I am a gang tagger."

He was allowed to leave, but not before officers told him they would keep his information on file. Kaleb denies ever vandalizing or tagging the school.

The episode enraged Kaleb's parents, who are now hoping the American Civil Liberties Union of Utah will take on their case and pursue legal action against the school district and police department. They've also contacted the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People because they believe police targeted their son because he is black.

Police have not disclosed the number of students similarly questioned that day, but Kaleb was not the only one.

The Winstons believe police officers broke a law that prohibits them from photographing juveniles who are 14 and under without a court order and are frustrated that parents weren't informed about the gang sweep carried out at the school on Dec. 16.

Lisa Winston, Kaleb's mother, said her son wasn't allowed to call when he was taken to the office. She found out what happened when Kaleb arrived home in tears, feeling bullied by police who insisted he was a gang member.

"Somebody, at some point should have called me while this was going on. They had no business photographing him. I didn't sign a release to photograph my son, I know that," she said.

School officials won't comment on the case, saying only that it remains under investigation.

Salt Lake City police Deputy Chief Terry Fritz, who oversees the city's gang unit, said he can't speak to specifics about Kaleb's case because of privacy laws.

But he confirmed West High officials asked for the gang unit's help after school resource officers reported an increase in graffiti vandalism around school as well as an "upswing in gang attire."

Officers organized theDec. 16 "gang saturation" as part of a community policing effort to dissuade kids from participating in gang activity, he said.

"We had a bunch of our gang unit officers go over to the school and field card any kids that were claiming gangs for the major reason of letting these kids know that we know about them," Fritz said. "It was successful, and the administration was happy."

Fritz said school administrators likely have the authority to photograph kids such as Kaleb if they believe a student has been involved in delinquent behavior, like tagging around the school. He noted some students involved in tagging aren't using gang graffiti but view themselves as artists trying to make their mark. School officials also consider the latter a crime.

He said the officers' goal is to establish a relationship with students — and steer those in need of gang prevention or intervention programs in the right direction.

"We try to get the kids to know us and let them know we're human, so they feel comfortable down the line [talking to police]," said Fritz, who used to work as a school resource officer. He said some students don't want to communicate with police and, in those situations, "sometimes those encounters are not fun because those kids don't want to talk to us."

Lisa Winston admits she became angry with police officers she spoke with at West High on Dec. 16 after her son reported what happened.

One officer told her Kaleb wore blue daily and that she wasn't aware of her son's activities. Another officer told her that although Kaleb didn't yet have a criminal record, he "looked like the type" to be a gang member because of his baggy basketball jersey and basketball shoes, she said.

She tried to explain that she keeps a close eye on her son, who works in the school's lunchroom and is a referee for the Junior Jazz basketball program at the Salt Lake County Recreation Center. The boy won an award for academic achievement named after President Barack Obama at his middle school last year, when he improved his grades. He's never had contact with police before Dec. 16 and has no juvenile record, she said.

Police officers chided Lisa Winston, she said, and accused her of "covering" for her son. She said she hasn't received answers from police or school administrators that she has contacted to complain.

"To this day, I've never seen the picture they took," she said.

Kevin Winston, Kaleb's father, said police used poor judgment.

"There was no evidence," he said. "It was illegal, and I don't want to see this happen to anyone's child."

The Winstons' complaint comes at a time when the Governor's Gang Task Force is researching possible changes to the law that prohibits officers from photographing or fingerprinting a child under 14 without a court order.

Officers can photograph children of that age when they've been arrested for a crime. But some law enforcement agencies believe the law is too restrictive because it hampers efforts to accurately document gang members as an intelligence tool at a time when gangs are recruiting increasingly younger proteges.

A change in law would mean police on the street could more quickly identify whom they are interacting with and help get kids into gang intervention programs if needed, Fritz said.

But the idea concerns some people like the Winstons, who worry kids too often are mislabeled as having gang ties.

Kevin Winston, a native of south-central Los Angeles who grew up in a neighborhood plagued with Crips gang members and other gang crime, said he's been vigilant to keep his teenage son away from gangs' reach. A community activist who has worked on several neighborhood beautification projects, Winston received accolades from the Salt Lake City Police Department in 2006 for saving a police officer whose gun had been taken away during a fight with a robbery suspect.

Kevin Winston said he's frustrated his son now does not trust the police department. The boy's attitude about school has also plummeted, he said, and Kaleb has quit drawing — a passion that once kept him excited about learning.

Kevin Winston worries that an intelligence file kept on his son will open up the boy to unnecessary scrutiny from police.

In addition to contacting the ACLU and NAACP, the Winstons plan to file a report with the Salt Lake City School Board citing their concerns with the gang saturation at school.

"This cannot happen to another kid like Kaleb," his father said.