This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Before he became one of Utah's most prominent residents and among the nation's most generous philanthropists, Jon Huntsman Sr. was a poor college student who couldn't afford an engagement ring for the woman he loved.

Huntsman, then at the University of Pennsylvania, turned to poker, and won a big chunk of the money he needed from wealthy classmates.

Later, while taking his young family on road trips, Huntsman would sneak into Las Vegas casinos to scrape together enough cash to pay for a hotel.

And after he became a billionaire chemical industrialist, he would still play blackjack and other table games, though, he says, for not as much money as you'd think.

"While this activity may shock some people, think about it: it would be ludicrous to believe that a risk-loving entrepreneur would not be drawn to gambling. Betting is what we do. That's who we are. And I'm pretty good at it."

Indeed.

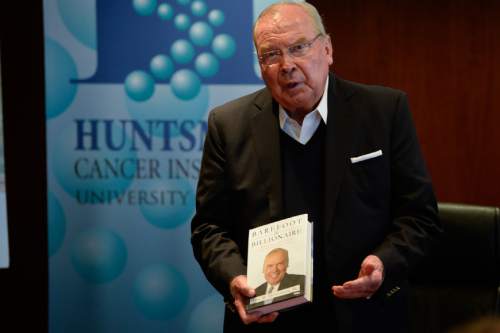

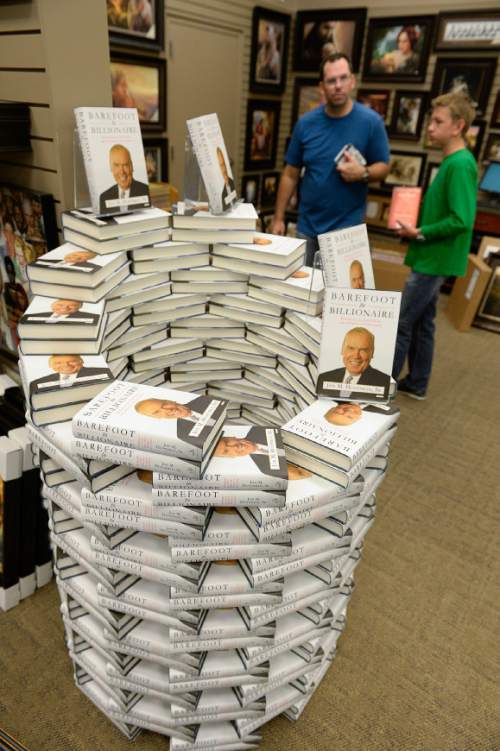

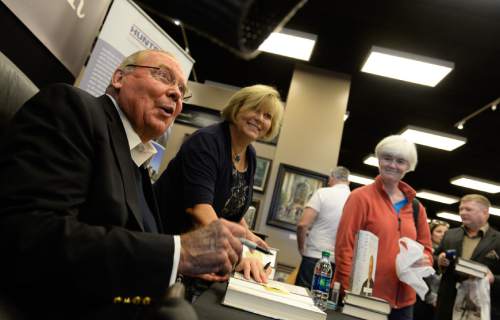

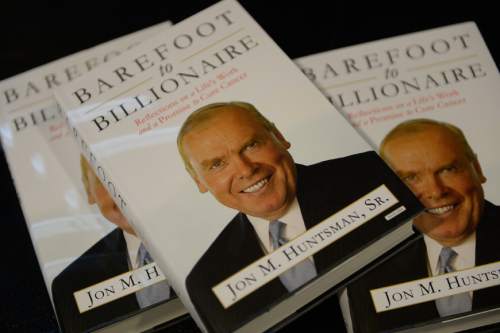

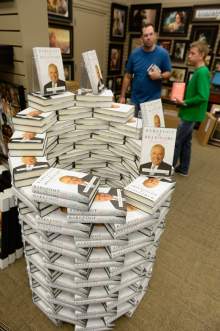

In his autobiography, "Barefoot to Billionaire," released in Utah on Friday and available nationwide on Oct. 30, Huntsman goes into detail about the big bets that resulted in his fortune and the personal struggles that led him to give much of it away. All proceeds from the book, initially priced at $35, will go to the Huntsman Cancer Institute, to which he has already given hundreds of millions of dollars.

He's been writing this 437-page book for three decades, for the past 12 years with the help of Jay Shelledy, former editor of The Salt Lake Tribune. Huntsman has decided the time is right to divulge parts of his life he has rarely spoken of, from his abusive father to the kidnapping of a son and the death of a daughter from drug addiction and eating disorders. He discloses how he handled his own cancer diagnoses later in life and how his family's meager financial status made him ashamed as a young man.

"Throughout my life, I have hustled to outrun the shadow of poverty," he writes.

—

Trusting emotion • He describes himself as emotionally volatile at times, but quick to apologize. His favorite part of business is crafting a deal face-to-face with another executive, where relationships, gamesmanship and raw emotion play just as heavily as financial statements and legal documents.

"I deal on emotions, which are irrefutable, rather than facts and figures, which are subject to interpretations," he writes.

Huntsman used those instincts to buy a raft of chemical plants in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a time when the surplus turned into a shortage and prices rebounded, he became wildly wealthy.

His contributions in Utah and the political career of his first born son, Jon Huntsman Jr., have made him a household name in the state.

Huntsman sprinkles business and personal advice throughout each chapter as he emphasizes his humble roots. He credits his business empire to hard work, good instincts and a willingness to gamble when necessary. He says he pulled his company from the brink of bankruptcy four times, in part by bluffing.

It's a largely romantic and sentimental view of his life, though it also includes some unexpected personal trivia. He's a big Elvis fan. His guilty pleasure is reading supermarket tabloids. While he once served as chairman of the board of the Utah Symphony, he doesn't like symphonies.

He recently expressed an interest in buying The Tribune — which he doesn't mention in this book, but he does recount how he tried to buy the LDS Church-owned Deseret News in the late 1980s, only to be denied by church leaders.

He also tackles the criticism he's received over the environmental impacts of his chemical empire, acknowledging that government regulation is needed and largely reasonable and that some in the industry have cut corners to save money.

He said he's proud of Huntsman Corporation's environmental stewardship, while at the same time suggesting that many environmental activists are hypocritical because they often wear and use products produced in his plants.

"I carry no guilt or shame about being a chemical industrialist just as people ought not to feel guilty or shameful about using the hundreds of items in their lives that are made of plastic," Huntsman writes.

—

Philanthropy • The second half of the book is largely devoted to his philanthropic ventures, primarily the cancer institute, over which he exerts considerable influence although it is nominally operated by the University of Utah. He said the institute's trademark is extravagant care for those with cancer and "entrepreneurial science" to find cures.

"I love the term 'entrepreneurial science.' It makes some scientists nervous, probably because it carries accountability, but that's just tough," he writes. "People who have cancer don't have the luxury of time. I give money and expect results."

He also expects to give away all of his wealth by the time he dies, creating foundations that he hopes to hand off to his children and grandchildren.

He also criticizes other wealthy Americans who don't give as much to charitable causes.

Huntsman, 77, doesn't want readers to see this book as the final chapter in his life. While his health has declined in recent years (he has a condition that swells his feet, making walking and standing difficult at times), his mind remains sharp. He plans to remain engaged in business and civic matters and he even hinted that he might write a second volume.

If he does, he already has a title in mind and it's something every gambler hopes to say — "Lucky, Lucky me."

mcanham@sltrib.com Twitter: @mattcanham