This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

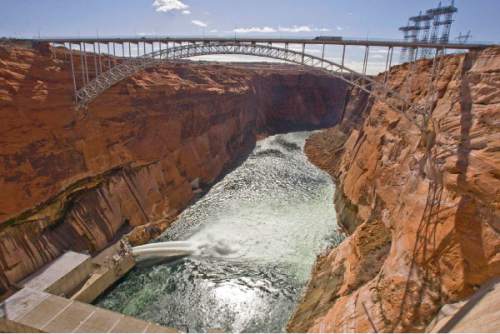

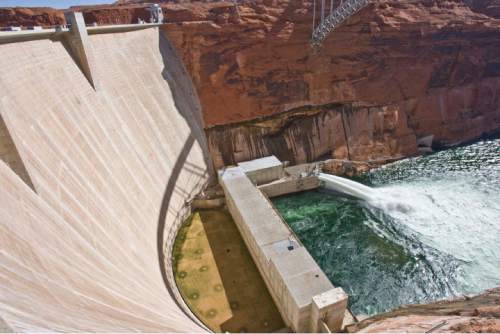

Federal officials opened the floodgates at Glen Canyon Dam on Monday, lowering Lake Powell and sending water rushing through the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. The five-day flood is meant to mimic conditions of the river before the dam was built, because the dam now blocks a majority of the sediment from traveling downstream.

How much water and sediment will move through the Grand Canyon?

The amount of water released over 96 hours will fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool every 2.5 seconds. The flood will distribute enough sediment through the Grand Canyon to bury a professional football stadium up to the lighting.

Who benefits from the flood?

Water managers and federal officials believe the increased sediment will improve beaches for campers along the river and breeding grounds for the endangered humpback chub. They say extra layers of sand will protect archaeological sites. Trout fishing should improve at Lees Ferry, about 16 miles downstream from the dam. Grand Canyon officials have warned river users and backpackers that campsites will be in shorter supply during the flood but will be more plentiful after it's over.

Does the flood have any impact on the water supply of the Southwest during the drought?

No. To create the flood, Lake Powell will shrink by 2 ½ feet. But Lake Mead in Nevada will rise by 2 ½ feet as the increased amounts of water flow through the Colorado River and to Lake Mead. The flood won't alter the amount of water sent between the two lakes annually, as monthly adjustments are made to account for the surge in water, officials said.

How many of these experiments have been done?

This week's experiment is the third since the U.S. Department of Interior declared them routine through 2020. The floods have accomplished the intended effect in building up beaches and sandbars, but the results often are short-lived. Federal officials want to study results over a longer time frame to see if the sediment can be maintained. "The natural ebb and flow of things historically would have been something like with floods," said Matthew Allen, a spokesman for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in Salt Lake City. "All these sandbars build up and wash away, build up and wash away."

When is the next high-flow experiment?

The Interior Department has said it would evaluate springtime floods starting in 2015, depending on the sediment available from Colorado River tributaries.