This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Their marriage license sits in a desk drawer.

Most of the wedding photos live on their computer.

And the memories endure only in their minds.

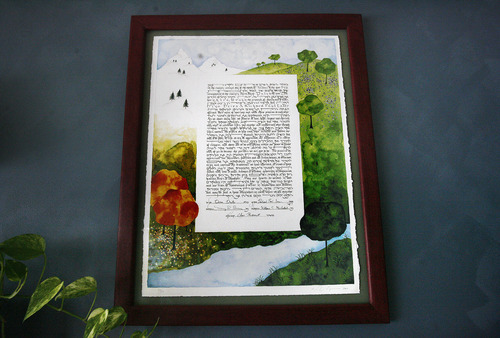

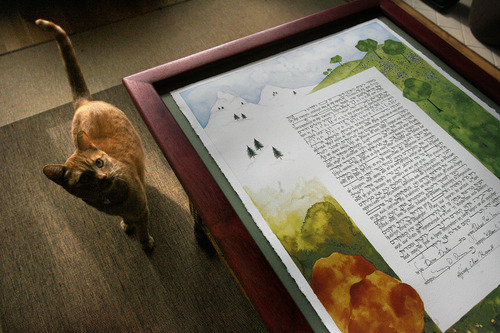

But their ketubah — a Jewish marriage contract — hangs for all to see over Rich Esser's and Dina Drits-Esser's living-room fireplace in a handmade, purple-heart wood frame. It's a personalized piece of art — featuring images of the four seasons surrounding the Hebrew and English text of the signed agreement itself — that the Salt Lake City newlyweds plan to enjoy for the rest of their lives.

"Every anniversary I think I want us to go through the text of it because we spent a long time choosing that particular text," Drits-Esser said, "and to kind of remind ourselves what our contract is to one another."

Throughout the Jewish world, the signing of the ketubah is an essential part of any wedding and a lifelong reminder of promises made on the first day of marriage. For thousands of years, ketubot (plural of ketubah) have been signed at Jewish weddings, in accordance with Jewish law. And though the contracts have changed over time, the tradition lives on, even experiencing, in recent years, a surge in popularity, with couples now often choosing ketubot with an eye toward displaying them in their homes.

"To a certain degree, it has to do with a pride in having this wedding and a pride in the Jewish aspect of it," said Rabbi Ilana Schwartzman of Salt Lake City's Congregation Kol Ami. "It is a piece of artwork that you and your beloved have together, and, for a lot of people, it may be the first piece of artwork they get together as a new family.

"At the end of the day," she added, "this is a document, Jewishly, that says you are married in the eyes of God and the eyes of the community."

Rich history

Rabbi Gail Labovitz, an associate professor of rabbinics at American Jewish University in California and author of Marriage and Metaphor: Constructions of Gender in Rabbinic Literature, said Jews have been using ketubot for about 2,000 years, and she has seen illuminated, or artistically decorated, versions of the documents going back as far as medieval times.

Now, however, many Jews — especially those who practice reform and some who practice conservative Judaism — choose a ketubah with wording that's largely about a couple's commitments to make a Jewish home together and/or support and strengthen one another throughout their lives.

That wasn't always the case.

Historically, ketubot were literal contracts, mainly detailing a husband's responsibilities to his wife. That included the amount of money a man would have to give his wife if they divorced and how much money she would get if he left her a widow — a sum, Labovitz said, that often depended on whether the woman was a virgin before the wedding or had been previously married.

In the ancient world, a ketubah frequently detailed the items or dowry a woman brought into a marriage and what she would get back if it ended. Labovitz said it also would include promises from a husband to a wife to provide food, clothing, medical care, ransom (if she got kidnapped) and sexual satisfaction.

Often the husband-to-be and father of the bride, or the fathers from each side, would work out the dowry details to be recorded in the ketubah. The document would then be signed before the wedding by two religiously observant male witnesses, who could not be relatives of the couple, in order to avoid conflicts of interest.

Much, however, has changed through the centuries.

"We don't tend to look at it as a binding contract these days," Labovitz said. "We do it much more symbolically now."

The right words

Many Jews now use one of a variety of set texts, depending on their denominational affiliation and personal preferences, which speak generally to a husband's and wife's lifelong commitment to each other. Orthodox and many conservative Jews' ketubot often include references to a man's responsibility to provide financially for his wife, Labovitz said, though conservative ketubot may be more egalitarian, spelling out a wife's similar responsibilities to her husband.

And reform Jews' ketubot often include no mention of finances, sticking only to issues of love, commitment and support.

Schwartzman, a reform rabbi who got married this summer, said she and her now-husband spent a lot of time talking about what they wanted their ketubah to say. She said she must have looked at about 1,000 ketubot online before she and her husband chose one that they felt best reflected them.

"We went back and forth about exactly what we wanted it to say because a traditional ketubah is actually a document of purchase, and that was not what I wanted," Schwartzman said. "I wanted it to be a marriage contract where it says we are going to support each other through our lives, and Judaism will be a part of our lives as we grow together."

Ultimately, they found a designer on craft website Etsy.com who helped them create a ketubah with blue text on a plain, off-white background to reflect the couple's clean, modern style.

"It's like any piece of artwork, insofar as everybody's got their own personal taste and personal style," Schwartzman said, "and to find something that speaks not only to you as an individual but to us as a couple is a really challenging thing to do."

Many Jews now order their ketubot through the Internet. Online forms allow couples to fill in their names along with those of their parents and the dates and locations of their weddings to be included in the ketubot. Ketubot can range in price from less than $100 to more than $1,000.

Ketubot are even available for same-sex, interfaith and non-Jewish couples.

Drits-Esser and her husband have an interfaith ketubah. She is Jewish and husband Rich is an atheist. She said her husband was actually the one who did most of the searching to find the right ketubah.

Because of their different beliefs, they wanted a ketubah that spoke more to their commitment to one another than to religion. The outdoors-loving couple also chose the ketubah they did because they liked the art of the four seasons.

"It's very pretty," Drits-Esser said, "and I kind of feel like it respects him and me."

They both signed the ketubah, as did their officiant and two friends who acted as witnesses, before their ceremony in the mountains at Alta this summer. They then asked the officiant at their wedding to read the text aloud during the ceremony so their guests could hear the promises they had made to each other.

Beauty of marriage

Some Jews still seek artists to create even more personalized ketubot.

A number of years ago, Salt Lake City artist Suzanne Tornquist was asked by an orthodox couple to create a ketubah for their wedding. They wanted something unique — a ketubah with images of themselves as well as other people in the wedding, such as the rabbi, friends and family.

Tornquist painted more than a dozen people into the ketubah, as well as a Torah scroll that winds around the happy couple. In the blue, purple and orange-pink background of the piece, a band plays Jewish folk music, and a broken wine glass, such as the one grooms traditionally smash at Jewish weddings, lies just beneath the text, near the groom's feet.

The idea of creating ketubot as elaborate pieces of art is a concept that's fallen in and out of style through the years, and the more recent trend of buying artsy ketubot that can be hung on a wall can be traced to the 1960s or '70s, Labovitz said. It's something that may have come back into favor as part of a larger movement to make Judaism more hands-on, more personal.

Plus, it's in line with the Jewish value of hiddur mitzvah, Labovitz said, the idea that commandments should not just be observed but beautified.

It's a value Tornquist's piece seems to reflect. Her one-of-a-kind creation is part of a long tradition of such works that she said continues to hold value today.

"To me, [marriage] is the most important decision you'll ever make in your life because everything else is affected by it," Tornquist said, "so when you sit down and actually put into words what to expect, it clarifies it in your mind, and it's also there for you to read."

Tornquist's own ketubah, from her conservative Jewish wedding in 1991, hangs above her bed. The text is written within the confines of a circle and surrounded by flowers and images of Israel.

She and her husband chose it because they thought it was beautiful, but they also ensured the text reflected what they felt were important elements of a marriage.

"The artwork was not as important," Tornquist said, "as thinking about what you were going to put in it."

About the ketubah

A ketubah is a Jewish marriage contract that is signed at a wedding. These contracts often feature text surrounded by art, and many couples hang them in their homes. Couples often choose the text of a ketubah based on their religious beliefs and personal preferences. Here's an example of part of the text from one Salt Lake City couple's interfaith ketubah, which they bought from http://www.galleryjudaica.com:

"As we share daily life, we promise to love, honor, respect, and cherish each other, to celebrate life's joys together and comfort each other through life's sorrows. We promise to help each other discover and follow our own true path in life, to try to appreciate our differences as a source of richness, and above all to do everything within our power to permit each of us to become the persons we are yet to be. We promise to appreciate our ancestors, families and all living beings, to treasure, enjoy and continue the traditions we have inherited, to create a home filled with love and peace, balance and freedom, generosity and compassion, healing tears and laughter. May our hearts be united in love and our lives be intertwined forever in tenderness and devotion and may we find a home everywhere on Earth where we are together." —

The art of faith — a yearlong series

P The Salt Lake Tribune is featuring a monthly series this year about religious art. Today: Jewish Ketubah art. To view previous stories in the series, go to http://www.sltrib.com