Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Cedric St-Jean and Blake Borgeson, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, work in the company's of

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Blake Borgeson, Ashwin Purohit and Cedric St-Jean, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, work in

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

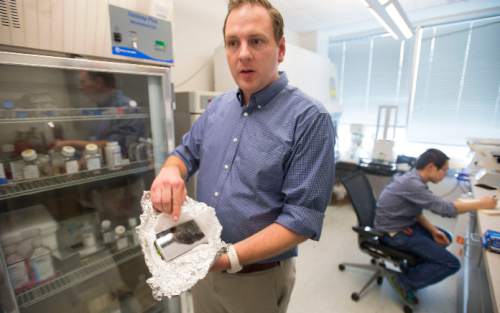

Recursion Pharmaceuticals CEO Christopher Gibson hold experimental plates created in the

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

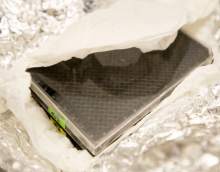

Experimental plates created Recursion Pharmaceuticals' lab in Research Park at the Univer

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

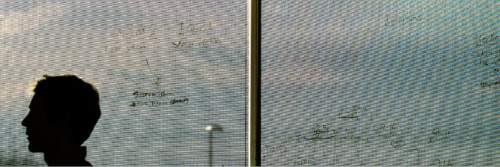

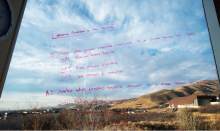

With notes written on the windows, Blake Borgeson, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, works on

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Dean Li, Vice-dean of research at University of Utah Health Sciences and Chief Scientific

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Dean Li, Vice-dean of research at University of Utah Health Sciences and Chief Scientific

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Ashwin Purohit, Cedric St' Jean and Blake Borgeson,of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, work in

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

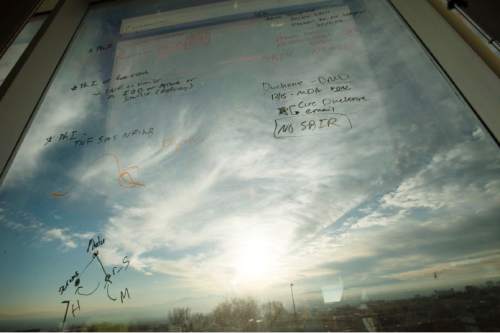

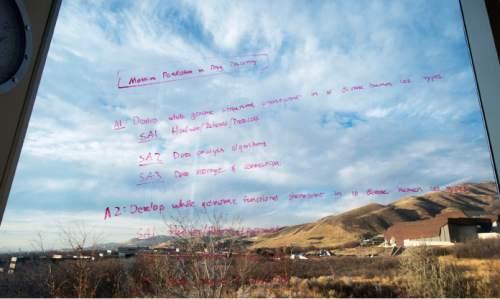

Notes jotted down from meetings and conversations are written on the windows of Recursion

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Notes jotted down from meetings and conversations are written on the windows of Recursion

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Recursion Pharmaceuticals CEO Christopher Gibson hold experimental plates created in the

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Notes jotted down from meetings and conversations are written on the windows of Recursion

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Han Han, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, feeds cells involved in biological experiments in t

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Han Han, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, feeds cells involved in biological experiments in

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Ashwin Purohit, Cedric St-Jean and Blake Borgeson,of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, work in t

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Cedric St-Jean and Blake Borgeson, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, work in the company's offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Blake Borgeson, Ashwin Purohit and Cedric St-Jean, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, work in the company's offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

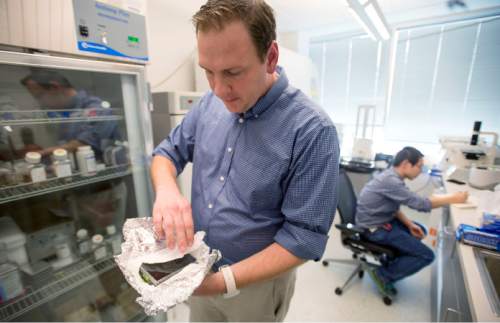

Recursion Pharmaceuticals CEO Christopher Gibson hold experimental plates created in the company's lab in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drugís success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Experimental plates created Recursion Pharmaceuticals' lab in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

With notes written on the windows, Blake Borgeson, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, works on his computer in the company's offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Dean Li, Vice-dean of research at University of Utah Health Sciences and Chief Scientific Officer at University of Utah Health Care, at the Recursion Pharmaceuticals offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Dean Li, Vice-dean of research at University of Utah Health Sciences and Chief Scientific Officer at University of Utah Health Care, at the Recursion Pharmaceuticals offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Ashwin Purohit, Cedric St' Jean and Blake Borgeson,of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, work in the company's offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Notes jotted down from meetings and conversations are written on the windows of Recursion Pharmaceuticals' offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Notes jotted down from meetings and conversations are written on the windows of Recursion Pharmaceuticals' offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Recursion Pharmaceuticals CEO Christopher Gibson hold experimental plates created in the company's lab in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Notes jotted down from meetings and conversations are written on the windows of Recursion Pharmaceuticals' offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

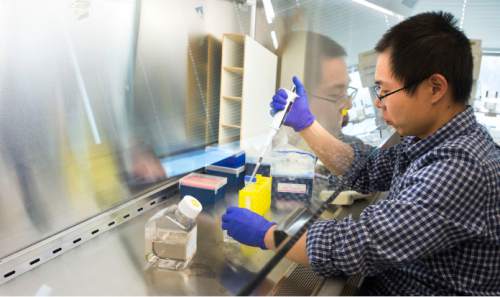

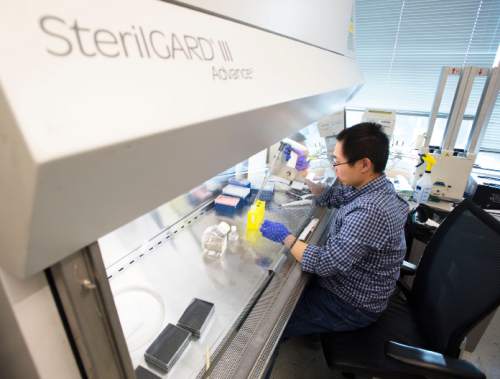

Han Han, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, feeds cells involved in biological experiments in the company's lab in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City in December. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drugís success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Han Han, of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, feeds cells involved in biological experiments in the company's lab in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.

Steve Griffin | The Salt Lake Tribune

Ashwin Purohit, Cedric St-Jean and Blake Borgeson,of Recursion Pharmaceuticals, work in the company's offices in Research Park at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Monday, December 8, 2014. Recursion Pharmaceuticals is a start-up company at the University of Utah and It's scientists and engineers are taking an unusual approach to drug development, and hope to develop 100 drugs in 10 years. The company says it's strategy is two-fold. Instead of targeting specific molecular targets for a disease, Recursion makes a human cellular model of the disease and then targets the resulting phenotype (its observable characteristics of the cell) by testing the ability of compounds to restore misshapen and diseased human cells to their normal appearance and function. Doing so is a good predictor of a drug's success or failure. And instead of starting from scratch with a new compound, their business model is to partner with manufacturers to salvage and repurpose drugs that passed early safety trials but never made it to market.