This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The judge's trial verdict in Utah's famous downwinders case begins with an eloquent opening statement that traces the idea of the existence of atoms to ancient Greece.

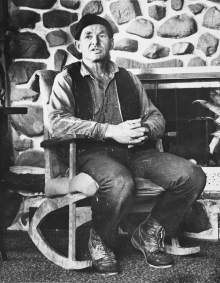

"In a sense," wrote U.S. District Judge Bruce Jenkins, "this case began in the mind of a thoughtful resident of Greece named Democritus some 2,500 years ago."

Then he drills down: "This case is concerned with what reasonable men in positions of decision-making in the United States government between 1951 and 1963 knew or should have known about the fundamental nature of matter."

And finally to the heart of the dispute: Whether those officials are "answerable to a comparatively few members of its population for injuries allegedly resulting from open air nuclear experiments conducted in response to such perceived dangers."

The 1984 decision is thorough, scholarly, factual and nuanced — and the most well-known and important ruling of Jenkins' career on the federal bench in Utah, which now spans 50 years and a remarkable swath of recent state history and notable cases.

Jenkins, said former federal Judge Paul Cassell, is "one of the true lions of the federal bench in Utah. He has been especially successful in helping to resolve some of the most complicated cases to come through Utah's federal court system in the last several decades."

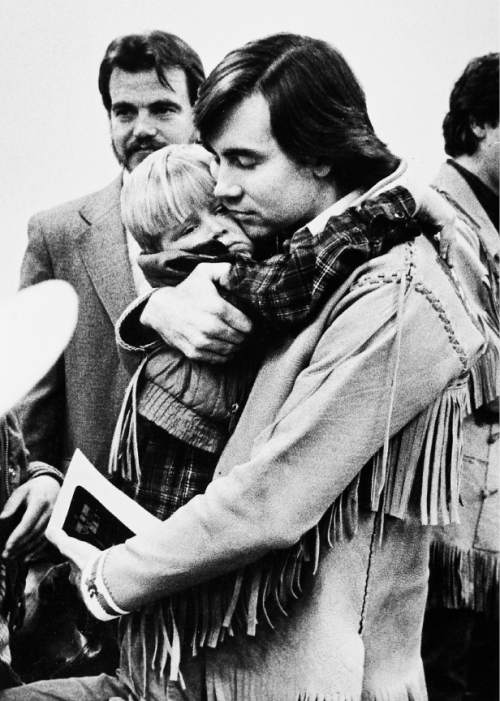

Colleagues, attorneys, court workers and others gathered last week to help Jenkins mark his five decades on the federal bench with tributes and stories about the judge, who also is well-known for his sometimes cranky berating of attorneys who appear before him ill-prepared.

—

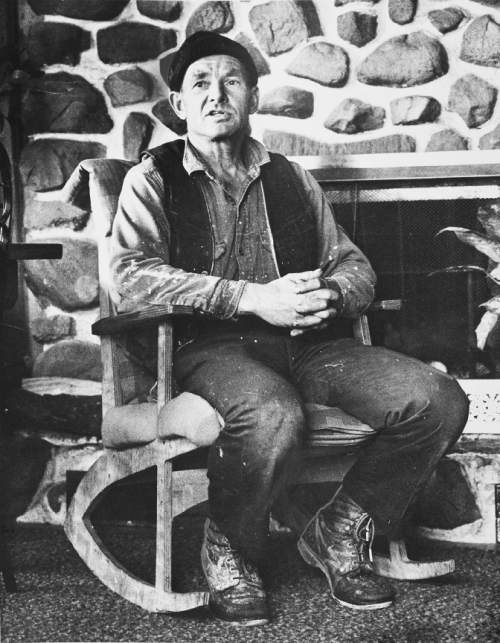

Law and politics • Now 87, Jenkins was one of five children born in Salt Lake City to an educator father and stenographer mother. He graduated from East High in 1944 and, after two years in the Navy, earned a bachelor's degree in political science in 1949 from the University of Utah and a law degree there in 1952.

That same year, he passed Utah's bar exam and then had short stints as an assistant Utah attorney general and a deputy Salt Lake County prosecutor. He also was in private practice for a time.

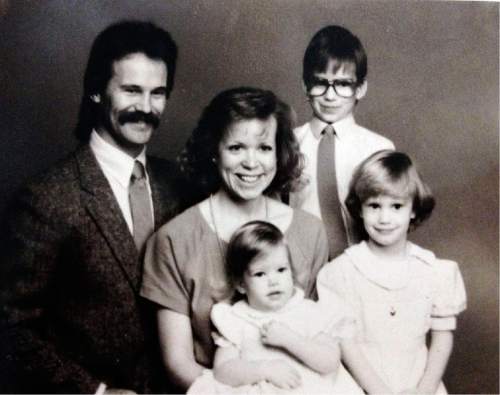

He married his wife, Peggy, in 1952. The couple had four children. Now they have 10 grandchildren.

Jenkins was involved in politics beginning in college, where he helped organize returning servicemen into an independent party that took over student government.

He was appointed as a Democrat to fill a vacancy in the Utah Senate, and then elected and re-elected, serving one term as Senate president. He helped lead major efforts to reorganize state government and to better manage its finances.

Jenkins resigned his Senate seat in 1965, when he was appointed as a referee in federal bankruptcy court by Chief Judge Willis Ritter, to whose house he had once delivered the Salt Lake Telegram as a youth and from whom Jenkins took a class in law school. In 1978, changes to bankruptcy laws relabeled the referees as judges and reformulated some of their duties.

Jenkins was nominated to the District Court bench in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter.

He was chief judge from 1984 to 1993, as the court expanded from two to five judges, court rules were rewritten, record-keeping was computerized and the courthouse remodeled.

—

The 'most challenging' case • Jenkins wrote his 490-page downwinders ruling after a lengthy bench trial that consolidated 1,192 lawsuits against the federal government, for deaths and illnesses that residents of southern Utah, northern Arizona and Nevada claimed were caused by fallout from the open-air testing of nuclear bombs in Nevada from 1951 to 1963.

The claims were "the most challenging of cases simply because of the human element," Jenkins said in a recent interview. "It's a little difficult to have a mother on the witness stand who talks about her child suffering from leukemia and bleeding from the orifices, the eyes and so on."

He sees his decision awarding damages to the victims and their families as holding the government accountable for decisions that were negligently made.

"Is the government saying," Jenkins said in the interview, "this testing is so important that it's all right to kill a few people — that's really the question — in contrast to saying when you do these experiments, be extremely careful and tell people about it and warn them?"

The ruling was overturned by the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals — "that bunch in Denver," Jenkins says — but the trial testimony and his decision ultimately helped persuade Congress to award compensation to the downwinders.

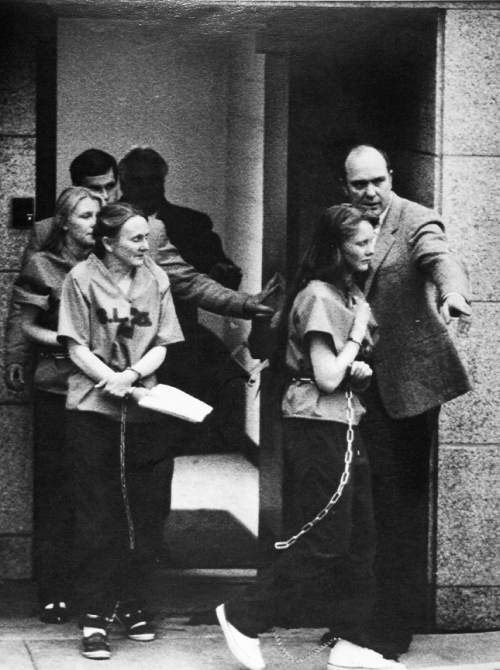

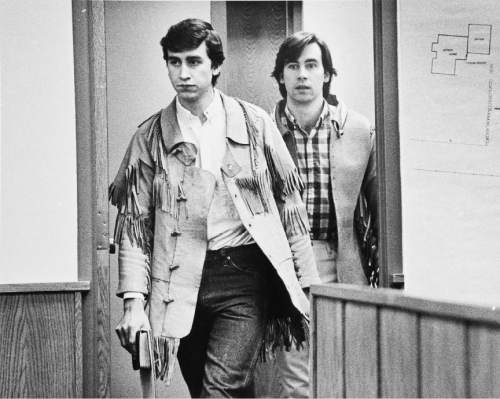

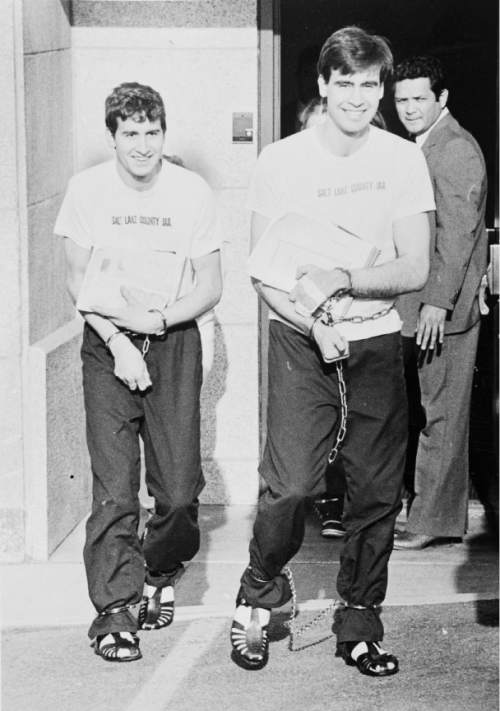

Other high-profile cases handled by Jenkins include the trial of white supremacist Joseph Paul Franklin, who murdered two black joggers, the Singer-Swapp polygamist bombing and armed-standoff case, the Bonneville Pacific securities fraud, the East High School Gay-Straight Alliance controversy and the lawsuit of a teacher fired because she was a lesbian.

He called the Singer-Swapp case "historically important" because Utah's District Court judges, acting together, declared sentencing guidelines unconstitutional. While a Supreme Court ruling overtook that decision, the high court years later reached the same conclusion, Jenkins said.

—

'Do some good' • Jenkins is known among attorneys for his sometimes cantankerous persona in court and his probing questioning as he tries to get attorneys to distill and clarify their claims and arguments.

Justice Carolyn McHugh of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals said she was intimidated by Jenkins when she first became a law clerk for him in 1982.

"But pretty soon I figured out he was just a great big teddy bear," she told a crowd of judges, attorneys, court workers and others at last week's gathering.

McHugh remembered that when Jenkins put on his robes in preparation for entering the courtroom, he would repeat to his clerks, "OK, kids, let's see if we can do some good."

Other former clerks remember Jenkins' calm demeanor when faced with unusual court antics or arguments.

John Boyle, now a New York attorney, read from the transcript of a hearing in which a tax protester who was in a hearing to set a trial date called Jenkins a traitor.

"I commend you in the name of Jesus Christ that the angels speedily take you to spirit prison and there retain you until the resurrection of the unjust," the man said. "In the name of Jesus Christ, amen."

"And everyone in the courtroom sat there just stunned," Boyle said. "Everyone, that is, except Judge Jenkins, and the next line of the transcript is: 'The court: OK, now let's fix a date.' "

Jenkins also has had a steady output of speeches, lectures and articles about aspects of the law and its administration, with titles such as "Managing the High-Profile Case" and "Dealing With Risk: The Courts, the Agencies and Congress."

He is a prolific reader and collector of books. Jenkins' interests vary from linguistics to feeding his "political junkie" habit with history to a large library on religion.

"The whole history of the Bible in many ways," he said, "is far more interesting than the book itself."

Jenkins grew up in a Mormon family but now describes his religious side as "Mormon by heritage, Christian by choice and Buddhist by inclination."

After 50 years on the bench, Jenkins said, he worries about some aspects of the system, such as how costly it has become, with attorneys billing in six-minute increments, which closes off the system to many people.

He's also critical of the minimum mandatory sentences created by Congress, denying judges discretion in sentencing those convicted of certain crimes.

But Jenkins reveres the legal process and the role it plays in this country. He sees the legal system as the place where conflicts don't have to be "played out in the gutter" and where even the president is not above the law.

"Most folks don't understand and don't appreciate — maybe that's a better word — that when we talk about the rule of law, you really have to switch that and say the law rules," he said. "And then you say Richard Nixon doesn't rule, law rules."