This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Draper • The Utah Transit Authority closed a contentious chapter Friday with American Indians over the protection of an ancient village site by dedicating a monument to Utah's tribes, built as part of a promise to mitigate disturbances from railroad construction.

"It is a time of healing for us," said Shirlee Silversmith, director of the Utah Division of Indian Affairs. "It is a new day. We want to move forward and allow our ancestors to rest."

Tribes, UTA leaders and Gov. Gary Herbert dedicated a large sundial — containing eight separate monuments for each of Utah's tribes — in the heart of a 250-acre preserve that protects the ancient Indian village along the Jordan River Parkway trail at about 13400 South.

UTA once caused an uproar by proposing to build its Draper FrontRunner station and mixed development at the village site.

UTA moved the station farther north after Herbert signed a proclamation creating the Soo'nkahni preserve, a Shoshone word for "many dwellings," to protect the 3,000-year-old village, the earliest known location of corn farming in the Great Basin.

In 2010, workers building the FrontRunner commuter rail line dumped fill dirt on part of the village site. As part of mitigation, UTA agreed to set aside $250,000 for archaeological preservation. That helped build the Draper monument and create archaeological preserves in San Juan County and Paragonah.

"We worked for months with the state and Utah's different tribal leaders to determine the best possible way to mitigate the construction of FrontRunner," said UTA President and CEO Michael Allegra. "We wanted a way to appropriately recognize the importance of this area and the state's Native American tribes."

He added, "We used rock from the surrounding areas. We used local designers to create a monument that would retain the right look and feel for the site," with plaques talking about the village and Utah's tribes.

"This project is a symbol of what can be achieved when people come together in a spirit of partnership," Allegra said.

"It's been a long journey. Maybe longer than we had hoped. But it's nice to see the completion of this," Herbert said. "I think this monument will stand as an enduring testament of the proud heritage of Utah's tribes.

"This is sacred land to us," said Jason Walker, chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation. "This is something we would like to stay pristine forever."

Silversmith said the site over time was home to a band of the Ute tribe, and "was also kind of a crossroads for other tribes that came through here to exchange. Shoshones, Paiutes and even Pueblos came up this way and they would trade."

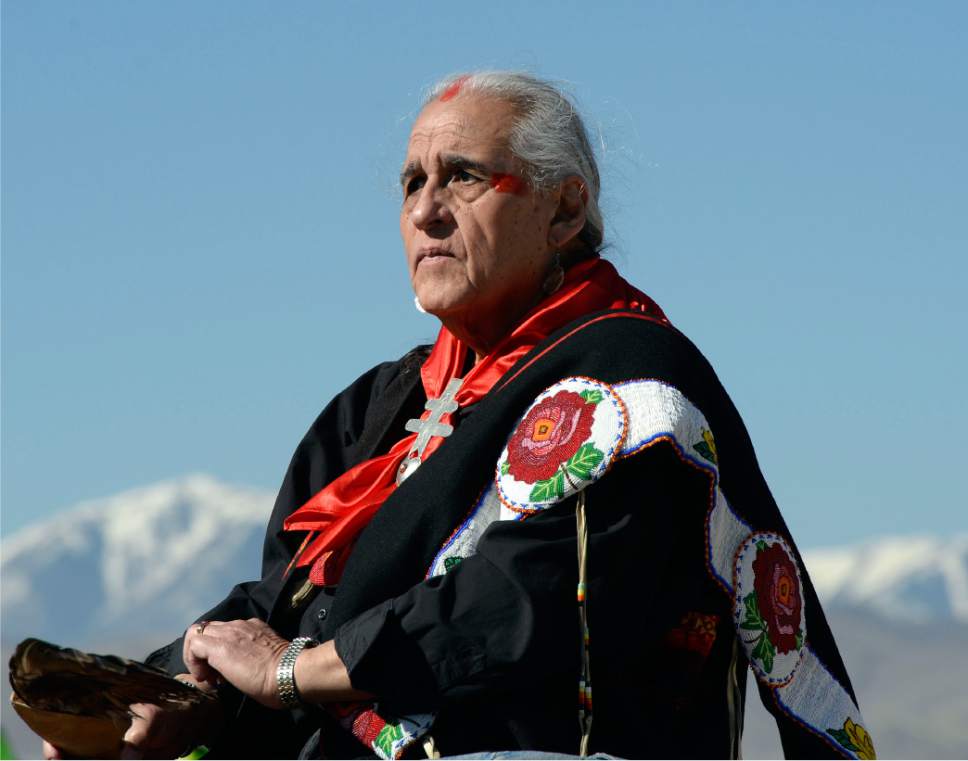

Lacee Harris, a Northern Ute Tribe spiritual leader, said before he gave the opening prayer, "It's a good thing, this memorial. But I was kind of sad that this is all we get…. This is all that's left — these plaques to talk about our people. I guess that's better than nothing, at least being mentioned."

Julius Chavez, a Navajo spiritual leader, asked God in the dedicatory prayer "for forgiveness for trampling on those things we're not supposed to do, for digging up those things that we're not supposed to dig up."

UTA's involvement with the Indian village has caused other controvery over time.

Forrest Cuch, former longtime Utah Indian Affairs director, said his protesting UTA plans at the village site was likely among reasons that Herbert fired him in 2011, although Herbert said Cuch was fired for insubordination.

Also in 2011, the state laid off the state archaeologist and two assistants — who blamed it on vocally opposing UTA plans at the site. However, the state said they were laid off because of budget cuts ordered by the Legislature.

Separately, Doug Clark was laid off in 2009 as managing director of business growth for the Governor's Office of Economic Development. He said in 2011 that was because he had refused to help with efforts to develop the site around the Indian village.

A 2010 legislative audit said former UTA board member Terry Diehl may have violated state law by using inside information to obtain development rights near the Draper FrontRunner station.

He later was pushed to resign from the UTA board, but not before being given a waiver from its regular one-year ban on former board members doing business with UTA.