This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

On paper, Sen. Mike Lee sure appears vulnerable. His unfavorable rating among Utahns is above 50 percent. Many establishment Republicans consider him too conservative and ideologically rigid. He hasn't proven that he can raise major campaign money.

And yet no one has stepped forward to challenge him in 2016, and it's increasingly likely that no big-name Republican or Democrat will. At this stage, Lee, the most conservative senator in the nation and Utah's most polarizing politician, appears to have an easy path to re-election.

He's pulled off a "magician's act," according to one Republican insider, who is baffled that Lee has emerged so politically strong just a year and a half after the freshman senator's anti-Affordable Care Act strategy led to a government shutdown and an avalanche of criticism.

So, how did he do it? Lee and his campaign team say it is simple: The power of his personality has won over former skeptics. He reached out to the business community and explained his conservative vision, which, boiled down to its essence, seeks a smaller, less-intrusive government and stronger civic organizations to help the needy.

That outreach helped, but it's not that straightforward. Other factors have cleared the field, some of which were in Lee's control but many others were not.

Lee has a collection of well-funded outside groups, such as the Senate Conservatives Fund and FreedomWorks, ready to spend millions of dollars eviscerating anyone who challenges their tea-party champion. Some potential challengers have shifted their gaze to 2018 and the seat held by Sen. Orrin Hatch, who says he plans to retire after 42 years in office. Others don't have the stomach to challenge a friend in what would surely be a bruising political fight.

"There was a time when the pot was stirring with some big Utah names, I think now the consensus is Mike Lee is our guy," said Rep. Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, who was one of the people who declined entreaties to challenge Lee.

—

Clock ticking • The Republican nominating convention is a year away, but anyone hoping to challenge an incumbent senator would have to start building a campaign team, increasing his or her name identification and raising money for a TV ad blitz.

"If you are going to make a run for the Senate," Chaffetz said, "you better darn well be in gear right now."

No one is even seriously thinking of putting it in gear, according to a series of interviews with prominent Republicans and Democrats.

Thomas Wright, a former chairman of the Utah GOP, was the last widely known Republican contemplating a Senate run, but he has decided against it. While he believes he could give Lee a tough race, Wright doesn't want to step away from his growing real-estate business or his young family. Josh Romney, the son of former presidential candidate Mitt Romney, has made no formal announcement, but has privately informed Republicans that, while he'd like to run for public office, he'll sit this one out as well.

Those two potential challengers have received the bulk of the attention, but there was an unprecedented, behind-the-scenes effort to find someone to confront Lee, and it was led by a man who is now a chairman of Lee's campaign committee.

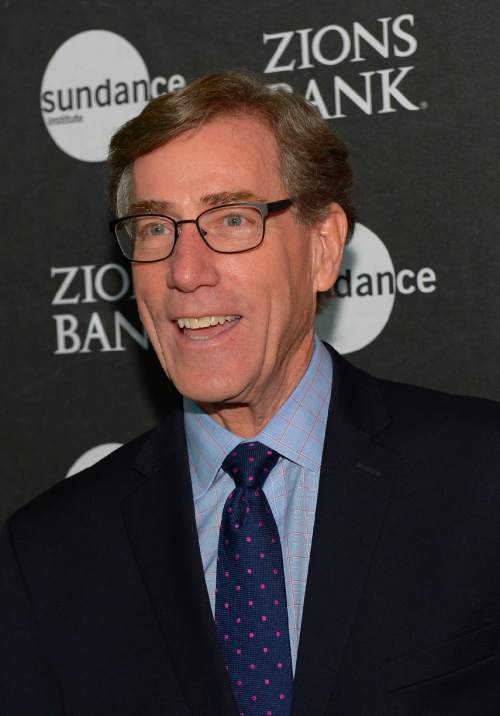

Scott Anderson, the CEO of Zions Bank, had been encouraging people to stand against Lee even before a stalemate in Congress led to a partial government shutdown in October 2013. Lee was the mastermind of that effort, which he hoped would end funding to Obamacare. It did not. He and Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, took the bulk of the criticism from Democrats and middle-of-the-road Republicans, while they were feted by the far right.

In the aftermath of what turned out to be a 16-day debacle, Anderson redoubled his efforts, commissioning Dan Jones to conduct a series of polls, which he hoped to use to recruit an establishment GOP standard-bearer. Anderson put the prospective candidates in tiers, according to the poll results. The four men best positioned to beat Lee were Chaffetz, Romney, former Gov. Mike Leavitt and Kirk Jowers, director of the University of Utah's Hinckley Institute of Politics.

All four declined, though Jowers considered it for much of 2014. Anderson also talked to candidates in lower tiers, people such as Wright, former Gov. Jon Huntsman Jr. and former state Sen. Dan Liljenquist, among others.

Some people expressed mild interest, but Anderson got no takers.

—

Insurgent as incumbent • Lee knew what Anderson was up to, but his campaign team didn't feel it was in a strong position to shut down the effort. In 2010, Lee had run an insurgent campaign to unseat then three-term Sen. Bob Bennett, a beloved figure among business leaders.

"When you challenge an incumbent, you really can't run around asking people not to challenge you," said Bud Scruggs, who has been a Republican insider for decades.

Recognizing his vulnerability, Lee hired well-connected people to represent him in the state. He named Derek Brown, then a state legislator, as deputy chief of staff, and hired Ryan Wilcox, another lawmaker, to be his northern Utah director. He asked Boyd Matheson, then his chief of staff in Washington, to move back to Utah to run the campaign.

But getting Scruggs to help him on a volunteer basis was key. Scruggs ran some of Sen. Orrin Hatch's first campaigns and was an aide to Govs. Norm Bangerter and Leavitt. He has long-lasting relationships with many Republican heavy-hitters, and he tapped those ties to set up a series of quiet breakfast meetings where Lee could explain himself and listen to the concerns of business leaders. Lee didn't offer any change in his positions or the way he would vote. He remains the most conservative member of the Senate, according to a recent Brigham Young University analysis. It also dubbed him the most "extreme," defined as having a voting record furthest from other members of his party.

But Lee emphasized in these private sessions that he can work with other Republicans and even Democrats on some bills, namely reforming federal prison sentences and digital privacy. And he said that he can help bridge the gap between the tea party and the establishment.

The way Scruggs sees it, many Chamber of Commerce Republicans have long mourned Bennett's defeat, and Lee, who spent his first years fighting high-profile battles on the Senate floor, never really reached out to build relationships. The hope was that allowing these community leaders to get to know Lee would lessen their desire to find a replacement.

"If you are a corporate leader or a civic leader whose primary goal in life is to get more than your fair share of federal dollars or incentives, then Senator Mike Lee just isn't a very satisfying meeting," Scruggs said. "I think people have taken awhile to get past that."

As part of that outreach, Scruggs said, he had some "candid conversations" with Anderson, even as Anderson was still seeking a candidate to back. Lee had his own chats with Anderson.

"I asked for his help and I asked for his input," the senator said, "and I continued to meet with him."

—

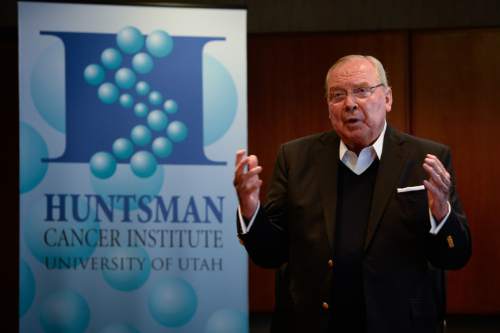

Lashing out • All of that private wrangling burst into public view in December, when Jon Huntsman Sr. lashed out at Lee in an interview with Politico and unveiled Anderson's behind-the-scenes recruitment efforts.

Huntsman Sr., a billionaire philanthropist who founded the Huntsman Cancer Institute, was upset that the shutdown stopped ongoing cancer trials funded by the government. He called Lee "an embarrassment" and predicted that Anderson would persuade someone to challenge him. Through a spokeswoman, Huntsman Sr. said he may have responded to questions about Lee with more emotion than he normally would, but that his criticism stands.

"He didn't think Senator Lee had really taken into account how that impacted many cancer patients," said Pam Bailey, a personal assistant to Huntsman. "He feels like there are better ways to solve problems than taking the government down to prove a point."

Anderson and Lee had a private meeting shortly after the Politico story appeared. By that point, Wright had emerged as the most likely challenger, while everyone else on the list had declined. Within days, Anderson gave $1,000 to Lee's campaign.

Republican insiders had figured Anderson might eventually back Lee, knowing the Zions Bank leader wants to be seen backing the winner in the election. But they were shocked that he would do it so early in the calendar.

In March, Lee's team announced Anderson and Huntsman Jr. as campaign co-chairmen and listed a series of early endorsements that included the names of people who had previously criticized him publicly, such as former Ambassador John Price.

Huntsman Jr. was the bigger name and coming on the heels of his father's stinging comments, his endorsement received considerable attention. He's more moderate than Lee, who served as Huntsman's general counsel when he was governor. Huntsman couched his endorsement as a man backing a friend.

"Mike got off to a rocky start, but I've worked with him and know from personal experience how capable he is," said Huntsman, who likes the bipartisan legislation Lee has sponsored. "I also believe the Republican Party must heal its internal divisions to be effective long term. Though Mike and I might come from different perspectives, it's commonality around the big issues that drove me to sign up."

—

Over before it begins • Anderson, who declined an interview request, has said little about why he's backing Lee. But political observers say his endorsement may well have ended the Senate race before it ever really began.

"That changed the trajectory of Utah politics for the 2016 election and beyond," said Frank Pignanelli, a prominent lobbyist and Deseret News political columnist. "What that means is that mainstream Republicans were saying, 'Lee can't be beat. We are accepting Lee.'

"Some might say he is still vulnerable, but when you have the blessings of Scott Anderson and others, it is almost impossible for someone to take advantage of his perceived vulnerabilities in the Republican Party," Pignanelli added.

Lee's vulnerabilities didn't end within his own party. He may be susceptible to a challenge from a well-funded moderate Democrat, someone such as former Rep. Jim Matheson, D-Utah, Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams or Doug Owens, who ran a tough race against Rep. Mia Love, R-Utah, in 2014. Some speculate that Anderson and Huntsman endorsed Lee early to help keep the seat in Republican hands. Utah hasn't had a Democratic senator since the 1970s.

There appears to be little threat from Democrats.

Matheson has taken a job with a lobbying firm in Washington, D.C., and accepted a board position with Sallie Mae, the student-loan company — not the actions of a potential Senate candidate. McAdams has said he will seek re-election as county mayor and won't be trying to leapfrog to the U.S. Senate.

Owens said he's keeping his options open, but is "not planning actively for anything in particular."

As it stands, Lee, whom many expected to face a fight for his political life, is the only Senate candidate in 2016.