This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note • This is the third in a five-part series about Utah educators given Teacher Innovation Awards this year for their use of technology in classrooms.

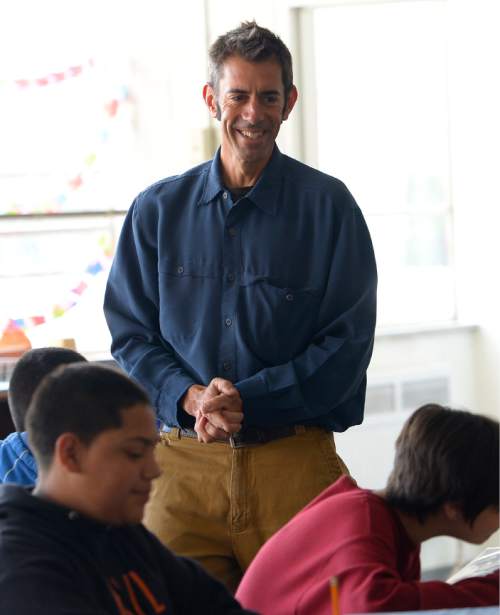

Kearns • In Chris Humbert's classroom at Kearns Junior High, the walls and tables are lined with models of futuristic cities and windmills made out of cardboard, straws and plastic cups.

It's just the latest batch of creations by Humbert's students, who during the year have used computer software to design digital models of wooden cars and now are working with a laser engraver to create custom dog tags.

Humbert teaches CTE, an acronym for the less-structured career and technical-education classes offered statewide to Utah's seventh-graders.

But it's Humbert's pre-education background as an architect for 18 years that truly informs the sense of creation that fills his classroom.

"I'm a huge believer in CTE and hands-on experiences for kids," he said. "I think both of those can really help education."

Humbert is one of five teachers selected for this year's Teacher Innovation Awards, sponsored by KUED and The Salt Lake Tribune. But earlier in his life, he said, he "never in a million years" thought he would become an educator.

Born in Colorado and raised in Buffalo, N.Y., Humbert moved to Utah in 1995. During his years as an architect, he had a hand in designing Park City's Olympic venues and early blueprints for what eventually would become Sandy's Rio Tinto Stadium, but the economic downturn of 2008 ultimately nudged Humbert out of his profession.

"When the economy tanks," he said, "there's no more building happening, which means no more drawings are needed."

His search for a new job led him to a special science and technology program run by the Salt Lake City School District that focused on sports and the outdoor-recreation industry as a way to appeal to students.

"It was right up my alley," he said. "It combined my love of sport with my love of technology."

When the funding for that program ended, Humbert chose to stick with education instead of turning back to architecture. But rather than go back to school for an education degree, Humbert went through the state's Alternative Routes to Licensure program, which allows career professionals to put their years of industry experience toward a teaching license.

"This is a lot more rewarding," he said. "Architecture wouldn't make you well up on a weekly basis like teaching does."

As many as 1,200 Utah educators are teaching provisionally while working toward an alternative license, according to Robyn Roberts, a licensing specialist with the state Office of Education.

She said the number fluctuates with the economy, as more and fewer jobs in various industries become available, and does not include provisional educators who have gone back to school for a traditional teaching license.

Humbert described the alternative licensure program as "powerful," but added that more could be done to make the process welcoming to noneducators. He attended evening classes for two years, he said, and the program could be better described as "stumbling blocks" to licensure instead of an "alternative route."

"When I started working here, I was still a licensed architect," he said. "I jumped through my last hoop last summer and got my license in June."

Humbert isn't the only one who believes the hard work paid off.

Kaleb Black, a 13-year old Kearns Junior High student, said he's a fan of Humbert, who is encouraging and maintains an upbeat classroom.

"He's so positive," Black said. "He always tries to cheer you up."

Principal Kandace Barber said the school is "really lucky" to have Humbert and his wealth of experience. She said Humbert makes an effort to be fun and engaging, and to encourage all students to participate.

"The way he teaches," she said, "it makes the kids feel like they're successful."

She also praised Humbert's collaborative spirit. While CTE is not part of the tested subjects that contribute to a school's grade, Barber said Humbert designs hands-on activities in his class that reinforce what students are learning from their math and science teachers.

"He is just an amazing teacher," she said, "because he shows the students a real- life application of what they're learning and he makes it hands-on."

Humbert said that because his CTE courses are outside the core subjects of math, English and science, he isn't tethered to a rigid testing schedule. That gives him and his students flexibility to take multiple stabs at a project before turning in a final design.

"I really try to let them explore," he said. "Innovation doesn't come from the first idea you have."

With four years of teaching under his belt, Humbert doesn't anticipate another career switch in the future. Teaching, he said, allows him to focus on the "fun" — designing and creating — part of architecture.

"I don't think I'm going to go back to architecture," he said. "I love this now and I can incorporate a lot of what I do in architecture into this."

Teacher awards

Five Utah teachers have been selected for the 2015 Teacher Innovation Awards, which are sponsored by KUED and The Salt Lake Tribune and celebrate the creative use of technology in classrooms.

The awards are given in the categories of arts, math, language arts, science and social studies.

The five winners are being profiled in a continuing series in The Tribune and a special program airing May 18 at 8 p.m. on KUED.

Previous installments featured:

Charlie Matthews, a teacher at the Park City School District Center for Advanced Professional Studies

Brandon Engles, a sixth-grade teacher at Shelley Elementary in the Alpine School District