This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Ogden • Old footage of his star point guard fumbling for minutes on end still replays in coach Randy Rahe's mind.

Damian Lillard was shaky, stammering, pulling at his clothes in a less familiar arena — a classroom at Weber State University — about six years ago.

"Early on in his career here, he was in public speaking. He'd have to talk in front of the class," Rahe said. "He was nervous and was struggling, fidgeting and not great at selling himself."

An instructor gave coaches the reel during Lillard's freshman or sophomore year, Rahe said, and probably without the player's knowledge.

The tape highlights the 24-year-old's transformation from onetime sheepish student to the more polished salesman he is now, according to his instructors, coaches and friends.

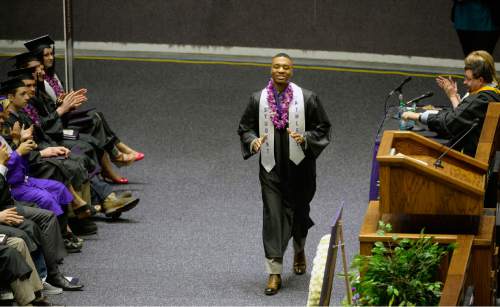

On Friday at the Dee Events Center in Ogden, Lillard's gaze held steady as he delivered what amounted to a brief acceptance speech.

Wearing his black graduation robe, the two-time NBA all-star spoke for about a minute to a crowd of 6,800 before signing autographs and taking selfies with students.

"It was a lot of the things that I picked up" at Weber State, Lillard said, that came together to become "the reason I've been so successful."

This summer, Lillard finished up an online computer-skills class and returned to campus for a final presentation.

Six credits shy of graduating, he was selected sixth overall in the 2012 NBA draft. The following season, he was the NBA Rookie of the Year. Nevertheless, he was determined to polish off his degree and return to Ogden.

He had promised himself and his mom that he would.

A few years ago, the college junior returned home to find his mother, Gina Johnson, sick.

"I needed to be off from work to heal" but couldn't swing the time off, said Johnson, who worked at a medical insurance company. "He said, 'Mom, I promise I'm going to go through college so you don't have to worry.' "

Johnson had been nudging her son toward the diploma at meals and while he played video games, she said.

Watching her son walk across the stage Friday, Johnson said, "means everything."

Melvin Landry, Lillard's AAU coach in third through fifth grades, agreed.

"One, it's for him. Two, it's for his family. Three, it's for everybody that's coming behind him," Landry said, including other young players from Oakland and dozens of little cousins.

Among fellow alumni of the Oakland Rebels Youth Basketball Club, Lillard now has joined the majority by earning a degree, said Landry, club president. Landry boasts that four in five former Rebels have earned a college diploma since the club's inception in 1987.

A broader look at Lillard's hardscrabble hometown shows a different trend, said Oakland High School coach Orlando Watkins. "We always talk about how Oakland has a lot of talent," Watkins said, "but kids don't get out of here with the grades issue."

About five years ago, Watkins brought Lillard in to talk to an Oakland High player with Division I potential but no patience for class. The effort stalled.

"The kid just couldn't figure it out," Watkins said.

Still, Lillard returns, hoping his story might resonate with other players.

When he visits, Watkins said, "he tells the guys — grades, grades, grades. Just focus on the grades."

It took the young East Bay native a while to develop the mantra when he began playing for Watkins, who required hour-long study-hall sessions at least four days a week, before practice and night games.

"For Damian, it was like, 'You gotta sit here for four days a week doing homework before you even practice?' " Watkins said.

But the discipline kicked in before long, he added. "He knew what he needed to do to get a scholarship."

In Lillard's first college season, the same hesitancy that bungled his classroom speech appeared on the court, where he feared being branded a ball hog.

"Believe it or not, we had to work on getting him to score," and also sharpening his ball handling and ability to shoot off screens, Rahe said.

That was about two years before an assistant coach wondered aloud during a summer workout if the kid the big schools passed up was starting to look like NBA material. Rahe nodded in response.

Meanwhile, Lillard was honing his sales skills in class.

By the time he reached professor Tim Border's negotiation classes, he had refined his pitch. Border recalled Lillard asking pointed questions in a scenario where he and two other classmates were peddling water softener.

"He came back this fall and stood in the classes I'm teaching and said, 'Guys, I'm using this material. I used it to negotiate my shoe deal. I'm using it to negotiate my salary,' " Border said.

Brokering the deal with Adidas executives counts as internship experience, said his Weber State academic advisor Carl Grunander, who recalls running laps in a campus gym as Lillard shot free throws below.

It didn't all come easily.

Childhood best friend and Weber State teammate Davion Berry, who recently returned from playing professionally in Italy, turned to Lillard for advice when both were new college students.

After high school, Berry was stuck playing Division II ball at Cal State Monterey Bay. He knew he could compete at the top level. But he hadn't convinced the scouts and he didn't have the GPA.

"I was kind of at a standstill," Berry said. "He just said, 'Keep working.' "

Twitter: @anniebknox Lillard was named Big Sky MVP twice while at Weber State. His 1,934 career points at Weber State rank him No. 2 in school history.

—

It's unclear how many of Lillard's teammates on the Portland Trail Blazer also have a diploma. The team does not keep track, but several played four years of college ball, noted spokesman Collin Romer. In Salt Lake City, six out of fifteen players on the Utah Jazz roster have a bachelor's degree, said spokeswoman Caroline Burleson.