This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It was his first chance to sell himself as a presidential candidate, and Mitt Romney was determined to make it memorable. The Massachusetts governor stood before a gathering of Southern conservatives in Memphis who knew little, if anything, about him.

And he began to sing.

"Born on a mountaintop in Tennessee, greenest state in the land of the free. …"

Just about everyone at the 2006 Southern Republican Leadership Conference knew the lyrics — the opening lines to the theme song from the Disney television series "Davy Crockett." Romney, though, changed the last line, turning his impromptu concert into a tepid joke about Tennessee Sen. Bill Frist, a physician who was obviously a popular local.

"Doc-torrr, Doctor Bill Frist, king of the wild frontier."

The crowd chuckled politely. One columnist winced.

"This sucking up to the hometown favorite coupled with Clark Griswold goofiness made me want to dive under the desk out of embarrassment for Romney and mankind," wrote Slate's John Dickerson. "The audience didn't care. They liked him and were still talking about him two days later."

Tall and lean, Romney wore a charcoal suit and a blue-and-white checkered tie. He stood behind a presidential-looking podium, and he fit the part. The 1,800 Republicans, mainly from the South and Midwest, came to size up the candidates. They wanted to know if Romney shared their conservative values and beliefs.

After his opening musical number, he dived into more traditional political fare. Romney criticized President George W. Bush for the growth in federal spending, then he praised Bush for fighting terrorism. He denounced gay marriage, then he said immigrants must learn English. The crowd repeatedly leapt to its feet and cheered.

When he finished, Romney made a beeline for the airport and left the wild frontier, not wanting to be there to hear the results of the presidential straw poll, the first of the 2008 election cycle.

With more than 2½ years before voters would pick the next president, nobody expected much of Romney, especially with Frist and eight others in the pack. The assumption was that voters, particularly Southern evangelicals, would reject Romney because of his faith, and yet the Mormon politician placed a surprising second in the straw poll.

Maybe the crowd liked his baritone.

In any case, the Romney acolytes went wild and, 1,500 miles away, Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman cheered with them. He sent Romney a handwritten note on his gubernatorial stationery: "Mitt, well done in Memphis! You made us all very proud. It was just a hint of what is to come! Respectfully, Jon."

Within four months, though, their relationship would be in tatters. In place of an admiring friendship rose a bitter rivalry that has festered in the years since.

—

Roots to rift • That sudden collapse is even more stunning when considering the ties between the families. While Huntsman had first met Romney while running for governor in 2004, their families have been intertwined for decades. They are distantly related through Mormon pioneers. Their fathers — Jon Huntsman Sr. and George Romney — were friends and successful business leaders. Huntsman's mother had shared a college dorm room with Romney's sister. And now, Mitt and Jon were governors, seen as rising Republican stars, who ran into each other regularly.

Romney headlined a Lincoln Day dinner for Salt Lake County Republicans in early 2005 in which he poked fun at Massachusetts and heaped praise on his "home away from home."

"Being a Republican governor in a blue state is like being a cattle rancher at a vegetarian convention," he joked.

Huntsman Jr. had introduced Romney at the $100-a-plate event, calling him one of the GOP's most impressive leaders.

"He is principled. He is brilliant. He has boundless energy. In fact, the only flaw I can find is that he attended BYU," Huntsman said, a nod toward his years at the rival University of Utah.

The Huntsman-Romney love fest continued when Romney returned to Salt Lake City for a Republican Governors Association fundraiser a few months later. Seated around a conference table at the Grand America Hotel, Romney privately asked Huntsman to help his nascent 2008 presidential campaign. Huntsman said he would, though the conversation wasn't formal or precise, with Romney using wiggle words about his "team" without actually mentioning what that team was trying to accomplish. But people in the room thought it was clear enough: Huntsman was backing Romney.

If it wasn't clear then, it certainly was when Huntsman huddled with Romney a few weeks later in a suite at the lavish Wynn Las Vegas hotel. Huntsman, accompanied by his wife, Mary Kaye, told Romney he wanted to be the first governor to endorse him and asked to be included in the campaign's strategy sessions. Romney demurred, saying he had yet to decide if he would run, but that he would welcome Huntsman's support if he did.

Huntsman underlined the commitment during a Deseret News editorial-board meeting. He told the board he had written a white paper on China for Romney "because he asked," adding that he had spoken to his friends in the national-security and foreign-policy world on Romney's behalf.

"I'll do whatever I can," Huntsman said. "Mitt would make an excellent candidate. I'm probably the only governor who has come out this early."

It's hard to read those comments as anything but an endorsement, and yet Huntsman would argue in the years to come that he never fully committed to supporting his distant cousin. His team would note there was no public announcement of a Huntsman endorsement.

"We had conversations, and he didn't want to talk very openly in our meetings," Huntsman recalled. "It was always 'what if' and 'maybe I'll be doing this.' "

—

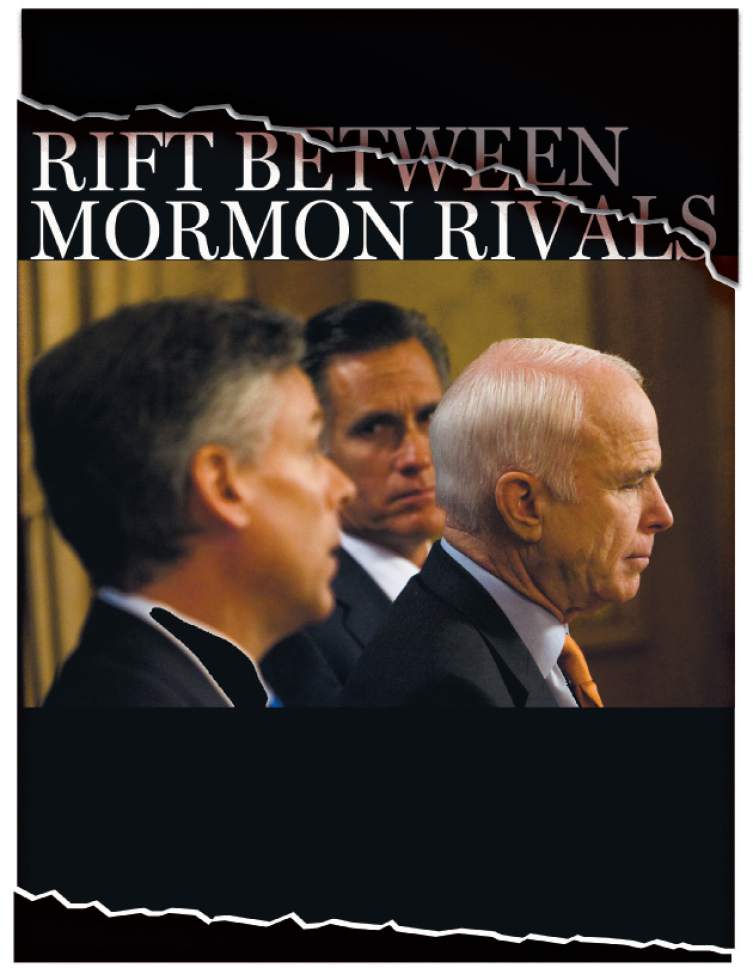

McCain is able • Utah's governor always had fashioned himself a maverick, even if he didn't use the word. He wanted to be a person who floated between the state's religious divide and the standard partisan splits. He gravitated to similar personalities. At a governors meeting in early 2006, he ran into Sen. John McCain, a likely 2008 presidential contender from Arizona. Huntsman asked him to headline Utah's Republican Convention in May. McCain agreed and then asked Huntsman to join him on a fact-finding trip to Iraq.

Huntsman was one of three governors and five members of Congress who went with McCain on the short visit, where they met with the Iraqi president and later the U.S. commander. The trip allowed Huntsman and McCain to bond over their foreign-policy interests.

A few months later, while Huntsman was on a regular lobbying trip to Washington, McCain summoned the Utahn to his office. Skipping the small talk, the senator asked Huntsman for his endorsement. He also wanted Huntsman to be a campaign co-chairman. Huntsman paused, caught off guard by McCain's bluntness. Then he said yes.

"He knew it was going to be a bombshell locally, and he knew outside the state of Utah no one was going to care," said a Huntsman confidant, thinking about Mitt and the Mormon connection. "He said, 'I'm going to take a hit for this, but I think this is the right thing to do.' "

Huntsman believed McCain was the right man on foreign affairs, his pet issue, and he felt taken for granted by Romney. He had written Romney that white paper on China and heard nothing back. He would offer help and get no response. Huntsman told Romney allies of his frustration and warned that he may bolt. Still, he heard nada.

"He just assumed that all the nice boys in Utah would just sort of hang around and wait for future guidance and light," Huntsman said.

One of his close advisers believes the split could have been avoided.

"If Mitt had really involved [Huntsman] in the campaign, I think he would have said yes to Mitt early on. He would have stayed loyal to that. If someone asked, he felt he was ready to commit."

McCain asked.

Huntsman broke the news to his staffers, many of them Romney admirers. They recognized that a big majority of Utahns swooned over their Olympic savior with deep Mormon roots, and they knew Huntsman's father planned to continue to back Romney as a key member of his national finance team. They braced for the inevitable backlash.

When McCain aides announced they had snagged Huntsman's endorsement, Huntsman ducked the news media, instead sending out spokesman Michael Mower to say the governor and McCain "share common viewpoints on many important issues." He also said the endorsement wasn't a slight against Romney.

Romney, his family and his advisers saw it differently. Romney learned about what he viewed as a clear betrayal from The Washington Post and immediately reached out to an adviser in Utah with ties to Huntsman. Mitt was incredulous and his wife, Ann, seethed.

Romney understood that Huntsman had been irritated, but how could he take such a drastic action? How could he do so without even the courtesy of calling? Romney saw the McCain endorsement as downright cowardly.

Spencer Zwick, Romney's go-between with Utah's political elite, vented to Jason Chaffetz, a one-time chief of staff who had left Huntsman's office nine months earlier. He also sent missives to at least two Huntsman aides, one of which said: "Not even a phone call."

Huntsman never phoned Romney to explain his decision, but Romney sure called Huntsman, delivering the harshest criticism he could think of: "Your grandfather would be ashamed of you!"

—

Rift remains • In the pantheon of put-downs, this would rank pretty low, but unpacking the power of those seven loaded words says everything about the way Romney perceived Huntsman's disloyalty. The grandfather Romney referred to was David B. Haight, a beloved Mormon apostle and one of the most influential people in Huntsman's life. Haight, who had died in 2004, was also a close friend of George Romney.

For Mitt, this was politics fused with religion and family. Endorsements are often overrated, but losing this one was embarrassing. How could Romney fail to secure the backing of the Mormon governor from Utah?

For his part, Huntsman didn't feel Romney had earned any advance notice of his plans.

"There were some angry calls," Jon's mother, Karen Huntsman, said in a nonchalant voice, dismissing Romney's outrage. "If I had a son running for president, and my best friend voted for his opposition, it wouldn't make me mad. That's your choice."

Karen Huntsman passed down that cool detachment to her eldest son, who has since torn down Romney in small digs and outright slams without so much as an emotional blip. He compared Romney to "a perfectly lubricated weather vane" in the same tone he might order a taco from one of his favorite street vendors. The Romney clan hit back, accusing Huntsman of being a coldblooded opportunist who put himself before party.

The big split in 2008 was just the beginning. Four years later, the 2012 election would fan smoldering resentment into flaming disgust in full view of the political world. Huntsman, then ambassador to China and an employee of President Barack Obama, left his dream job for his own White House run.

He wouldn't have made the move if he didn't view Romney as a weak front-runner. Romney, for his part, saw Huntsman as another GOP gnat to swat aside on his path to the nomination — one he would relish crushing.

Members of both families deny a feud exists and instead offer polite, politically correct compliments about their counterparts. They often say they just don't know one another very well.

Behind the facade, though, lie two political tribes that deeply dislike and distrust one another. Family friends, confidants and former aides, given anonymity so they could speak without fear of reprisal or of damaging relationships with the families, say the raw feelings have persisted.

"It's almost like they are trying to be king of the Mormons," said one person who has professional and personal ties to Romney and Huntsman. "They are two royal clans who have had so much success financially and politically and in other ways. It is not easy for them to be second place."