This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Mitt Romney jettisoned his red tie in a Denver hotel suite and sat with his family, relishing his dismantling of President Barack Obama in their first presidential debate.

Romney had appeared aggressive and engaged, while the incumbent looked like he wanted to be anywhere but that stage.

A documentary crew followed Romney afterward as he rather modestly told his sons and their wives that presidents tend to have a hard time in their first toe-to-toe encounter, because they're stunned at this "whippersnapper" challenging them. Then he flipped through his debate notes and handed them to his son Matt. On the upper right corner, the word "DAD" was written in all caps.

"I always think about Dad and about [how] I'm standing on his shoulders," Romney said. "There's no way I'd be able to run for president if Dad hadn't done what Dad did. He's the real deal."

Mitt Romney never really rebelled as a teen. Instead, he desperately wanted to be like his famous father, George Romney. He grew up expecting to run a car company because his dad did. He ran for office largely because his dad did. Even Romney's love affair with young Ann Davies resembled his father's instant infatuation with Lenore LaFount.

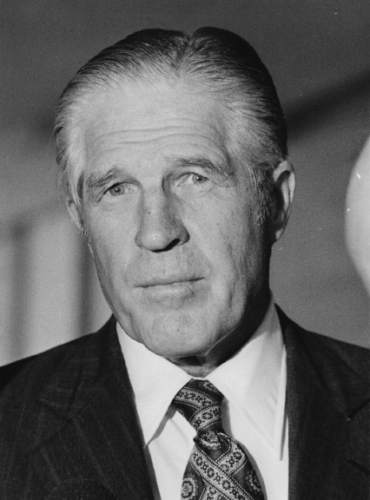

George Romney is the man Mitt modeled his life after, at least his adult life, because his father's upbringing was humble and more than a little unusual.

Raised in a polygamist commune in Mexico, George Romney became a war refugee in the United States after the Mexican Revolution. His parents, who were not polygamists, lost everything and struggled financially for years as his father worked as a homebuilder in California, Idaho and eventually Salt Lake City.

George was a lath and plaster man for his father while in high school and while attending college. He never graduated. Instead, he got a job in Congress, which led to a position with an automobile association and eventually a spot at American Motors, a Detroit-based automaker that rallied behind the compact car at a time when the glamorous cars were wide, long and made of real metal.

While in school, he fell deeply in love with Lenore LaFount, an aspiring actress who had landed a $50,000 contract with MGM. Romney chased her from one coast to the other. She eventually abandoned her acting career in 1931 to be with him, a man who made far less than her but had big ambitions. He would call it "the best selling job I ever did."

They had their fourth child — Willard "Mitt" Romney — more than 15 years later and no one in the family would relish George Romney's political rise more.

—

Young politician • At age 14, Mitt Romney stood by his mother on the stage where his father announced his campaign to be governor of Michigan in 1962, a decision George Romney made only after a religious fast.

At the time, he was not only leading American Motors but he was also in charge of a state constitutional convention, during which he promised no politicking. Young Mitt caused a bit of a stir when he told reporters his father made the decision to run before that convention ended. George Romney quickly told reporters he didn't make the "final decision" until he was driving away from the convention to his home in posh Bloomfield Hills.

A few months later, Mitt made headlines again when, at an Independence Day event, he said: "It's really fun to be here in the United States for the Fourth of July for the first time."

The eyebrow-raising comment, which drew groans from the campaign staff, was true. The Romneys had a vacation home in Canada, where they celebrated the most American holiday each year. Years later, Mitt would laugh about it.

"That wasn't a great line," he said. "Yeah, I was not particularly adept at my communications with the media."

But Mitt was enthusiastic, and his father loved having him around the campaign. He would man the campaign headquarters' switchboard and helped set up booths at county fairs.

"I would introduce myself and shout out to people walking past, 'You should vote for my father for governor. He's a truly great person. You've got to support him. He's going to help make things better.' "

George Romney won that election running as a centrist Republican with a big heart. One of the unintended consequences was that Mitt got teased regularly. At Cranbrook, the private school he attended, classmates would belittle him saying he was "no George Romney."

"I had the impression that Mitt was struggling for respect when he was at Cranbrook," said Eric Muirhead, a classmate who is now a writing teacher in Texas. "Mitt suffered because of his father's importance."

That didn't make the younger Romney resentful. He interned for his father when he was 16. But Mitt would be an ocean away when his dad made the leap into presidential politics in the lead-up to the 1968 election.

—

Mitt's mission, father's campaign • During his mission to France for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Mitt Romney would be forced to communicate through letters. As is true for many missionaries, the relentless rejection began to irritate Elder Romney, who started to dream up alternative ways to spread his faith's message, everything from public singing to basketball games to archaeology lectures. In a letter home, he wrote: "Why even last Sat. night, my [companions] and I went into bars explaining that we had a message of great happiness and joy, and that we would like to talk to anyone who had a few minutes. Amazing how that builds one's courage."

Courage, maybe, but the tactic didn't win many converts. In those 30 months, he would say he helped convert 10 to 20 people.

In letters, Romney complained. His father sympathized. George Romney wasn't sure he converted anyone during his mission to Britain. He tried to buck up his son by pointing out that Mitt's future wife, Ann Davies, and, later, her little brother, Jim, converted back in Michigan because of him.

"This makes two converts here that are certainly yours so don't worry about your difficulty in converting those Frenchmen!" his father wrote in a birthday message to his son in March 1967. "I am sure you can appreciate that Ann and Jim each are worth a dozen of them, at least to us."

Beyond the stream of letters from his parents and his siblings, the family regularly sent Romney a collection of newspaper clippings about his father's presidential pursuit. He tracked it all: his father's rise in prominence, race riots in Detroit and his father's tour of U.S. slums.

He also followed along as his father was pilloried for saying he was "brainwashed" by U.S. generals over the Vietnam War, a remark that severely undermined his standing in the contest.

The only chance Mitt Romney had to help his dad's campaign was in December 1967, when George Romney came to France. His son acted as a translator as the candidate spoke with national leaders before embarking on another trip to Vietnam, where he vowed he wouldn't be misled by military leaders again.

At that point, nothing could stop George Romney's slide in the polls, and he dropped out in February 1968. Mitt, who had no access to a TV, radio or phone, heard about it in a letter from his dad.

"Your mother and I are not personally distressed. As a matter of fact, we are relieved," George Romney wrote. "We went into this not because we aspired to the office, but simply because we felt that under the circumstances we would not feel right if we did not offer our services. As I have said on many occasions, I aspired, and though I achieved not, I am satisfied."

—

Taking on a Kennedy • Mitt Romney thought of that letter in 1994, when he found himself restless at Bain Capital, the venture-capital firm that made him wealthy.

He decided to launch his first bid for elected office, running against the legendary Sen. Ted Kennedy in Massachusetts, where Romney had lived since his Harvard days.

While his father was the man he revered, Mitt also drew inspiration from his mother, Lenore, who was a U.S. Senate candidate in Michigan in 1970, though she fell short. Her style was a contrast from her husband's — a peacekeeper and behind-the-scenes strategist — an approach that her son would emulate.

"Mitt's more like my mother," his sister Jane once said. "Mitt's the diplomat. Mitt knows how to smooth things."

As he decided to make the leap into public life, Mitt Romney wanted his parents' approval, but George Romney wasn't keen on the idea. He urged his son to wait another six years. "I thought he ought to get better known," said the elder Romney, who then was 86.

George Romney always had told his kids that if they were going to run for office, they should hold off until they were financially stable and their children old enough to handle the public scrutiny. That's something Mitt Romney later would tell his own children. At the time of his '94 Senate run, Mitt Romney was 47 and his youngest boy was 14. When George first ran for governor, Mitt was 14.

Romney followed the pattern his dad set in 1962. He sequestered himself and his family. They fasted and prayed. A short while later, he announced his run for the Senate, vowing to give it everything he had, even though he privately thought he would lose.

"We recognized that there was no way I was going to beat him." Romney said. "A Republican, white, male Mormon millionaire in Massachusetts has no credible chance."

—

Chip off the old block • Once Romney formally entered the race, his father lent his full support, making public appearances and eventually moving into the apartment above his son's Belmont garage so he could campaign full time. Voters often asked George Romney about the similarities between himself and Mitt.

"He's better than a chip off the old block," the father would say. "No. 1, he's got a better education. No. 2, he's turned around dozens of companies while I turned around only one. And No. 3, he's made a lot more money than I have."

Kennedy's campaign slammed Romney for Bain Capital deals that led to layoffs, a strategy Mitt's opponents would rely on for the rest of his political life. But in that race, Romney ignored the digs. Next Kennedy hit Romney on his faith, particularly questioning why he would support a church that previously had discriminated against black people. The LDS Church didn't allow black males to hold the priesthood until 1978.

"Where is Mr. Romney on those issues in terms of equality of race prior to 1978 and other kinds of issues in question?" Kennedy asked.

Mitt Romney couldn't keep quiet any longer. His father had been an outspoken supporter of civil rights and was dogged by this same question. Mitt, who was a counselor to an LDS stake president in 1978, said he first heard that his faith would let blacks hold the priesthood on his car radio. He pulled over and wept with joy.

Romney responded to Kennedy's assault by calling a news conference in late September 1992. Reporters crammed into his Cambridge campaign headquarters to hear Romney echo the words Ted's brother John F. Kennedy used 32 years earlier when questioned about his Catholic faith. "I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the church does not speak for me." He scolded Kennedy for trying to "take away his brother's victory."

Romney then took questions from reporters, while his father stood near the TV cameras. At one point, George Romney got so worked up that he blurted out: "It is absolutely wrong to keep hammering on the religious issues, and what Ted is trying to do is bring it into the picture."

Kennedy started to walk back his questions on Mormonism, largely because he didn't need to keep up the attack. Kennedy was walloping Romney in the polls and eventually won re-election easily.

Romney returned to Bain Capital almost immediately, ready to put the 1994 defeat behind him. His father moved back to Michigan and his regular routine.

The next summer, George Romney had a heart attack and died at age 88 while on a treadmill in his home in Bloomfield Hills. Lenore knew something was wrong when she woke up and didn't see the single rose that George placed daily on her dresser.