This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When "Papa" Yaw Reneer first met his new older brother, Julie Reneer says, it was more like a reunion of two old souls.

It sustains her now to think of tender moments like that night at the airport, when Yaw made a beeline for Brigham's stroller before greeting his new father and sisters.

One family photo shows Yaw trying to read to Brigham in bed. In another, Yaw plants a kiss on his lips.

Those were taken six years ago. Yaw is a healthy 12-year-old. Brigham, then 14, died 21/2 months after their first encounter.

Without Yaw — whom Reneer adopted "through some pretty miraculous miracles" and who initially horded and ate to excess the few American foods he could stomach, fearing a shortage — Reneer might never have visited Ghana.

Without Brigham — afflicted by an ultimately terminal degenerative storage disorder — Reneer might not appreciate the joy that a disabled child can bring to its family's life.

Utah and BYU players will soon share the same field to work a fundraiser for children halfway around the world, and it will be as much because of Yaw and Brigham as anybody else.

They're indispensable.

Which brings us to the importance of this football clinic.

In parts of Ghana, disabled children are often viewed as "spirit children," besetting their families with evil and misfortune.

Ghana passed a disability rights bill in 2006, and tribal leaders have more recently banned the practice of feeding poison to disabled children. Still, there are reports of children left in the wilderness for animals to eat, or dropped on beaches for the waves to carry away.

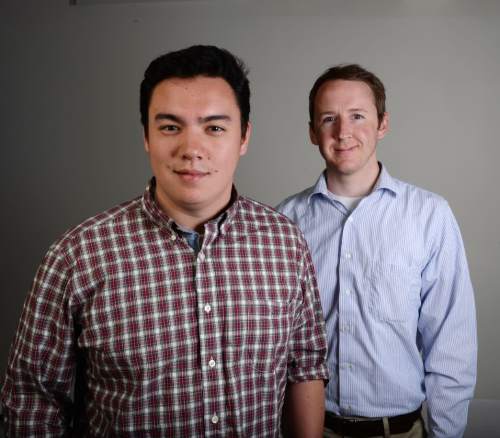

Acacia Shade is a small Utah nonprofit founded by Holly Cloyd, who, like Reneer, adopted a Ghanaian child in 2009.

Cloyd was later approached by Helena Obeng-Asamoah, overseer of Ghana's orphanages, and told that abandoned disabled children receive insufficient care from the government.

She pleaded for help.

So Cloyd enlisted Reneer and a board of volunteers, and in September 2013, they opened a home in Accra for four disabled children whose ages and original names they'll never know, but who have made dramatic strides thanks to their attention.

Now, Acacia Shade hopes to build another house on land donated by Idaho-based Ghana Make a Difference, which provides homes for children who are susceptible to child trafficking. A nearby school would allow Acacia Shade to integrate their children into society.

That's the impetus for the football clinic, which runs from 10 a.m. to noon Saturday, July 11, at BYU's practice fields.

Headlining is Ghanaian Detroit Lions defensive end Ziggy Ansah, and New York Jets outside linebacker Trevor Reilly also plans to attend.

Utah director of player personnel Fred Whittingham — a childhood friend of Reneer's — expects to bring eight-10 current Utes. Former BYU safety Craig Bills is working to round up some Cougars.

The no-pads clinic is for ages 5-14. Cost is $35, and participants receive a T-shirt, a small lunch, and photos and autographs from the players, who are volunteers. Reneer said 100 percent of donations will go toward building a home in Ghana.

You can also donate $35 to pay for an underprivileged child to attend through the local Boys & Girls Club.

Find out more at acaciashade.org.

mpiper@sltrib.com Twitter: @matthew_piper