This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

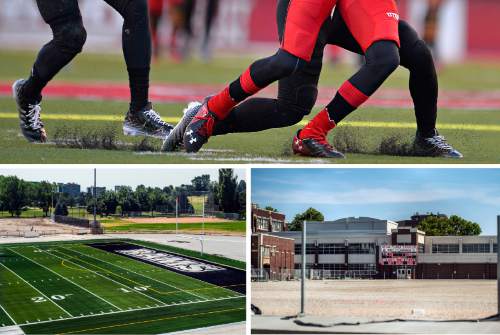

Have you ever watched a football or soccer game on TV and seen those little black balls splash up from the field when a player runs or slides? They are tiny little pieces of recycled tires, called crumb rubber, which are used as infill on artificial-turf fields.

They replicate the look and feel of a real grass field while offering a durability that makes them cost-effective relative to the upkeep necessary to maintain actual grass. Meanwhile, they also provide cushion and stability, helping to prevent concussions that were so prevalent on old, concrete-like AstroTurf fields.

Such benefits prompted the Salt Lake City School District to install multipurpose turf fields at West, East and Highland high schools in Salt Lake City, to be used for football, soccer and physical education.

But they also have their detractors.

Critics argue the use of crumb rubber has side effects as relatively benign as increases in knee injuries and skin infections, and as serious as causing cancer. Such concerns have led to the substance being banned in several states.

Is all the drama warranted? Well, it all depends on whom you ask.

—

Cause for concern? • In October, NBC News published a story about University of Washington women's soccer coach Amy Griffin, who compiled a list of 38 soccer players around the country who had contracted a form of blood cancer that she believes might come from the use of this synthetic turf.

Paul Schulte, the executive director for auxiliary services for the Salt Lake City School District, saw that story, but he puts little stock in it. He says that while 38 cancer-stricken athletes is not an insignificant number, it represents a tiny percentage of athletes known to have serious or dangerous diseases. More than 11,000 people use turf fields every day in the United States.

Meanwhile, he points out there has already been research conducted on the potential health effects, including studies by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Consumer Product Safety Commission, both of which concluded there is no substantial connection between crumb rubber infill and any health risks.

"That's all anecdotal; there's no research at all in that [NBC] story," Schulte said. "It's difficult because you've got to kind of rely upon the folks who take the scientific approach. Most of the research I've read are from folks that analyze."

However, both the EPA and the CPSC conceded their studies were conducted more than five years ago and that their research scope was limited.

The NBC story caught the attention of some Utah high school coaches, including East High School's girls' and boys' soccer coach, Rudy Schenk, whose teams will play on turf next school year.

Schenk noted that reading about it raised some red flags, but not enough to warrant major concern.

"I talked to someone a little bit about it, and, yes, I think they should look into that," said Schenk, who has been coaching soccer for more than 25 years, including the past eight at East. "But I don't think you can draw any significant conclusions from just that small piece of information."

He added that his more immediate concerns about the new fields have more to do with more conventional injuries. Several studies, including ones conducted by Reuters and the NFL Players Association, show an athlete is likelier to injure a knee or ankle on a turf field than on grass.

"I think the thing for me that I would be more concerned about is some of the structural issues that kind of arise, the physiological, structural issues like [ACL tears], or something like that," said Schenk.

Brody Benson, the football coach at Highland, echoed Schenk's reaction to the NBC story, saying he's not going to worry about it until there's conclusive evidence that the crumb rubber poses a health risk.

"I'm a football coach, and I'm looking at it [in terms of] what we're doing on it on a daily basis," he said. "Obviously, if it came out and they said this is causing this stuff, then obviously it's an issue."

—

Definite benefits • While conclusive links between artificial turf and potential health risks are elusive, there are benefits to having a turf field instead of grass.

The first and arguably most beneficial aspect is a financial one — turf fields can save schools thousands of dollars per year in maintenance costs.

Schools can spend anywhere up to $50,000 per year maintaining and preparing grass football and soccer fields they play on. Turf fields can cost between $500,000 to $1 million per field, so it can take 10-20 years to be cost-effective, which Schulte said was a big factor in the process.

"We did a cost analysis over the next 20 years, and we believe it will come back to the district in a very positive way," Schulte said.

One of the other most important aspects for the Salt Lake City School District deciding on the turf fields was the overall usage. Most football fields, especially during the season, are only used on game day in order to limit wear and tear and, by extension, the amount of regular maintenance needed. Schulte said "the ability to use the field for increasing instructional space" was a big motivator in the decision.

"The fields, for the most part, didn't hold up very well, and so you primarily use them for football games," Schulte said. "Now we'll be able to put P.E. fields on there. ... The use by students per square foot increases at a significant rate."

He also said that the schools and their students aren't the only people who will benefit.

"Certainly in Salt Lake, green space is at a premium — whether it's soccer or football or whatever the case may be — so that's going to open up some opportunities for the community, as well," Schulte added.

The football and soccer coaches at East, West and Highland are very much in favor of the new turf fields, for a variety of reasons.

"The [turf] is a little bit more forgiving nowadays, as opposed to the [old] artificial turf," said West head football coach Keith Lopati, comparing it to the old AstroTurf he played on while in college. "When I played, there was no forgiveness whatsoever, and it was playing on cement — I mean literally playing on cement."

Benson noted that turf fields provide consistency because they don't get torn up the way grass does, and players can use it in any weather.

"We're a running team, and we have a tendency to chew up our field pretty good," Benson said. "Now you know you're going to always have good footing. There's going to be consistency. There's no holes, there's no dips or divots or anything like that."

—

Split opinion • Naturally, the company installing the fields, FieldTurf, stands by the safety of its fields. FieldTurf is one of the world's largest synthetic turf manufacturers. The company notes on its website that it makes fields for professional teams, colleges and thousands of high schools and parks around the country. FieldTurf cites several studies in claiming on its site, "Synthetic turf is and has always been safe. There is no legitimate scientific or medical evidence that synthetic turf poses a human health or environmental risk."

Not everyone is willing to take the company's word for it, though.

New York state, New Jersey, California, Maryland and Connecticut have looked at the potential dangers of crumb rubber-based fields. While their research was largely inconclusive, there have been initiatives in many of those states to use alternative forms of infill instead, because of the potential associated health risks. The New York City Parks and Recreation Department decided to stop installing fields with crumb rubber in 2009. The next year, the Los Angeles Unified School District followed suit, opting for alternative infill material like cork or sand.

But after doing extensive research over a period of several years while the turf proposal was reviewed, Schulte and the Salt Lake District believed there wasn't enough evidence that the fields were unsafe. The Utah Board of Education agreed, approving the installation of the fields.

"Our comfort level was that most of the research that we found were fairly positive that the health risks were not putting our students in harm's way," Schulte said.

"There's not a risk any more so than there would be, say, for the inherent risk of participating in any athletic event," Schulte added. "The risks are just inherent to the athletic competition."

Twitter: vincent_pena7