This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

"Did you know," Larry Krystkowiak asked in his Montana drawl, leaning over his lectern, "that there's a lot of cheating in college basketball?"

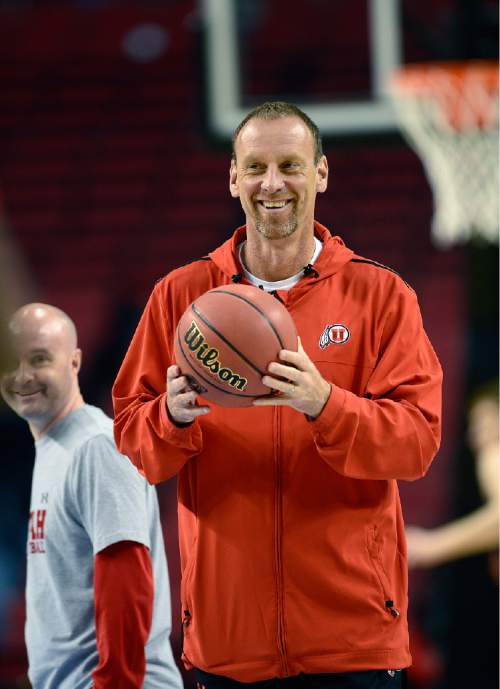

His earnest delivery prompted some chuckles among the audience of roughly 40 people. But Utah's men's basketball coach wasn't going to leave it hanging without telling a story. He asked two compliance officials if he could venture on.

The tale: He was once recruiting a top-level player, and the player (or his representatives) called Krystkowiak in the middle of the night. They told Krystkowiak the recruit's transcript would cost the Utes $50,000, and "it'll probably cost you $50,000 more to sign him."

That's the reality Krystkowiak sees in college basketball recruiting, a world less like "Hoosiers" and more like "All the President's Men." To run a successful program — which Krystkowiak vouches is clean — is a tough business.

"Meanwhile, I'm getting reprimanded for having the wrong kind of water bottle on the sideline at the NCAA tournament," Krystkowiak said, a bit exasperated.

Krystkowiak's address on a rainy Wednesday was a part of the Hinckley Institute's Sam Rich lecture series. The keynote lecture will be next week, when Moneyball author Michael Lewis visits on Sept. 24.

But Krystkowiak's lecture on relating Moneyball concepts to recruiting was well worth the free admission.

The biggest takeaway from his meditations on recruiting: While some schools look for mostly talent, the Utes coaching staff also hunts for character. Krystkowiak said that's been a priority from Day 1 of his tenure in 2011, when he told his assistants: "We're not going to recruit any turds."

Krystkowiak explained that his program has been built by four-year guys who might have been undervalued in the recruiting process, but have proven invaluable to what he describes as a "player-driven program." The Utes expect their players to enforce good work habits, academic standards and staying out of trouble.

He said he first wished for more cultural control when he was coaching the Milwaukee Bucks.

"If you have the opportunity to design culture, design it," he said. "Otherwise the pre-existing culture is going to naturally start permeating into your program."

The tenets of Utah's culture, he said, are simple: Play hard. Don't take bad shots. Go to class. Stay out of trouble. If a player can commit to those rules, he'll be welcome at Utah.

That includes players who first came into the program in 2011, a group that mostly transferred out the very next year. Krystkowiak went into some detail about that six-win group, saying he had been upfront to them about their deal: They'd get good coaching, good educations, quality treatment, but it was only for a year.

"We coached the heck out of them," he said. "To be honest with you, I don't know if I could ever have that much fun winning six games ever again."

Krystkowiak said honesty remains a central principle as he recruits. While his staff is swinging at bigger prospects now following a Sweet 16 appearance than they were four years ago, he tries to keep expectations grounded and not talk about NBA careers or one-and-done seasons. Instead, he centers discussions on opportunities players will have and lessons they'll learn.

Recruiting, he said, is a bit hit-or-miss. The best you can hope for is getting a guy who is willing to work hard. He offered several examples: In the year Javaris Crittendon was the No. 1-ranked recruit, Steph Curry called him up at Montana and asked if the Grizzlies would recruit him. Damian Lillard was also overlooked by Montana, eventually finding a scholarship at Weber State.

But one of the better examples is closer to Krystkowiak's heart: When his team was on exhibition in Brazil, the coaching staff learned a four-star recruit — Krystkowiak didn't name him in the lecture, but was referencing Julian Jacobs — decommitted from Utah. Coaches were devastated, "nearly in tears," but quickly scanned their board for who was next up.

Their eventual signee: A junior college guard named Delon Wright.

"For two years I've pretended like I'm some kind of genius," Krystkowiak quipped. "Sometimes you get lucky with a kid that is ultra-talented and has the right character."

Part of getting lucky is seeing all the guys out there. Krystkowiak watched 120 games in July, he estimated, pulling days that last 14 hours.

He'd like to see more skill development at the prep level, something he thinks isn't emphasized enough. He felt like it was something he developed playing in open gyms and going one-on-one against other players. He once walked into a gym where nine of his players were sitting around because they didn't have enough guys for a 5-on-5 game. He admonished them to play 3-on-3, 4-on-4 or something else — just play.

He also wishes more basketball players would be multi-sport athletes. One of his sons plays lacrosse. He himself had a few sports under his belt, including high school tennis.

"I got my butt kicked every time I played," he said. "But I had fun."

While there's yearly speculation whether Krystkowiak will one day return to the NBA, he seems to find a home in the college game. He said he's long dreamt of being a professor, and in his current job he finds similar satisfaction in mentoring younger players.

His upcoming senior night next spring against Colorado — the first he's experienced with players he recruited and coached four years — will be difficult to get through as he honors players like Jordan Loveridge, Brandon Taylor and Dakarai Tucker, he said.

"This is going to hit me pretty hard," he said. "I might need help coaching the game."

This much is for sure: He doesn't need help spinning a good yarn or two.

Twitter: @kylegoon