This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Until it ended in a deadly torrent, an excursion by seven canyoneers killed earlier this month in Zion National Park went entirely by the book.

The group of California and Nevada hikers had reserved a backcountry permit Sept. 14 for Keyhole Canyon, as required for all slot canyons demanding ropes and harnesses. Rangers issued the permit that morning in accordance with park guidelines, which restrict canyoneering only when flash flooding is imminent — but not when flooding is "probable," as the weather forecast had warned. When a flood warning was issued that afternoon, rangers suspended permits and announced that Keyhole Canyon was closed.

But it was too late for the seven victims.

In the aftermath of Zion's deadliest day, park officials, visitors and recreation advocates are re-evaluating a permit system that controls traffic in the canyons, but leaves questions of risk largely up to the user. Some say that's the intrigue of a wilderness experience: It gives people an opportunity to engage nature on its own terms and face its challenges without outside interference.

Others say the park should do more to keep visitors out of harm's way.

—

Narrow window of warning • Under existing guidelines, rangers have two ways to prevent hikers from going into a canyon after they have reserved a permit: They can try to convince canyoneers that their plans are too risky, or, when flooding is imminent, they can deny a permit. The standard for permit refusal — a flash-flood warning by the National Weather Service (NWS) — is not, on its own, likely to keep all visitors out of the canyon when a storm hits. That's because flash floods, like the one that killed the group in Keyhole Canyon, often occur midday or later, after most canyoneers have picked up their permits.

By 7:30 a.m. on Sept. 14, rangers had issued a permit for Keyhole Canyon to Linda Arthur; her husband, Steve Arthur; Gary Favela; Muku Reynolds; Mark MacKenzie; and Robin Brum, all from Southern California; and Don Teichner, of Mesquite, Nev. At that time, the NWS pegged the chance of rain at 40 percent and the flood potential was "moderate" — or "probable" in the terminology of Zion's rangers. Several members of the group then attended a basic canyoneering course.

At 8:35 a.m., NWS reported the chance of rain had risen to 50 percent. But more than five hours passed before a flash-flood warning at 2:22 p.m. triggered the official closure of canyons.

By that time, the victims were out of cellphone range and making their way to Keyhole Canyon, their families have said. Between 3:30 and 4:30 p.m., park officials say, the group dropped into Keyhole's twisting series of rappels and narrow, cold water pools on the park's east side.

The seven were not the only ones to enter Keyhole during the flash-flood warning. Three other canyoneers passed the group at the first rappel. They would emerge less than two hours later, narrowly avoiding the approaching thunderstorm.

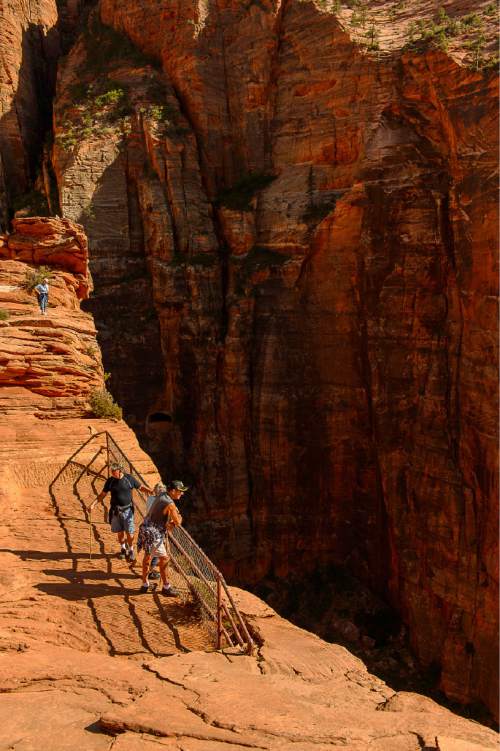

Many canyoneers need only one to two hours to complete Keyhole, making it one of Zion's shortest technical canyons. It also has a relatively low exposure to floods, owing to its watershed of only 1.5 square miles — a contrast to the many southern Utah slot canyons that can accumulate rainwater draining from storms many miles away.

"People look at Keyhole as, 'Yeah, that's a cute little canyon. Not much of an adventure. It's easy to do,' " said Rick Praetzel, managing partner of Zion Adventure Co., a Springdale outfitter and guide service. "But then there's the water."

A flash flood in a slot canyon is considered one of the gravest dangers a hiker can face in Utah. Knee-deep water becomes impossible to stand in at about 5 mph, Praetzel said. A brief storm can send a wall of water and debris plunging between narrow canyon walls with avalanchelike force, dislodging massive boulders and redepositing everything in its path, from tree trunks to the bodies of large animals.

The magnitude of danger means every incremental change in storm likelihood deserves concern, Praetzel said.

"If you're at a 20 percent chance of rain, you need to think hard about whether you're going, if you're going to need to have a trip plan that has you in a canyon for a relatively short period of time," he said. "At 30 percent, it's time to just start making alternative plans. At 50 percent, you just can't go."

—

'We are not weather experts' • The question remains whether that judgment is best made by the park or the canyoneer.

Despite visitors' access to canyons during flood potential ratings up to and including "high," only two other permit-holding hikers in Zion appear to have been killed by flash floods since the park began issuing canyoneering permits in 1998: Two California men died that year in the Narrows. Although several others have endured close calls and injuries due to floods, their numbers pale next to the roughly 40,000 each year who obtain permits to descend Zion's slot canyons and emerge unharmed.

But the vast majority of those likely went out when the flash-flood potential rating was "dry" or "low."

"We don't put 'moderates' out that often, and 'highs' are quite rare," said NWS meteorologist Pete Wilensky. Since Sept. 10, only two days have received a rating of "moderate" or above: the day of the Keyhole Canyon flood, and the day after, weather service.

Donnie Benson, a member of the Wasatch Mountain Club, said the park "absolutely" should restrict permits when the flood potential is "probable."

"Anything below that, the people can make their own judgment call," she said. "Those [seven] people should have not been issued a permit."

It's unclear how visitors might react to that level of restriction, said Zion ranger Therese Picard. Flash-flood potential ratings are issued for the entire park, with no distinction among its various areas, different times of day, or individual canyons. If rangers deny permits parkwide because of a flood-potential report issued at 2:30 a.m. and disappointed visitors then see only sunshine pass over their long-desired route, it could hurt rangers' credibility.

"We are not weather experts," Picard said. "How do we know which canyon is going to flood? Is the rain going to go north of us? South of us? Even the National Weather Service is constantly updating their forecast. What we can do is provide the information that we have."

The risk of damaged trust between visitors and rangers is real, agreed Travis Heggie, a professor of tourism and leisure at Bowling Green State University, who has studied national park safety. Although Heggie said he "would probably stop issuing the permits if there was a reasonable probability" of flooding, he acknowledged the chance that visitors "will think, 'We're just talking to the angry ranger,' and not give them much credence."

"It would help," Heggie added, "if people knew that they were dead serious when they stopped issuing the permits or said there was a probable chance of [flooding]."

On the other hand, he said, the act itself of issuing a permit can produce a false sense of security that conditions are safe and user judgment is not needed. "I have seen that time and time again — the attitude that the government would keep us safe," Heggie said. "But when you go out in nature, nature happens."

Denying permits at lower risk levels could increase that sense of security, argued Bill Dunn, outfitting manager for Zion Adventure Co.

"If you close access to all of the canyons when there's a 10 percent chance of rain or moderate chance of flood … the park service is opening themselves up for a scenario where there's an implied level of safety if it's less than that standard," Dunn said. "You're opening yourselves up for more liability."

—

Choice and responsibility • A storm gathered as Spencer Daniels waited for a lagging group of Boy Scouts at the end of Echo Canyon during a day of "moderate" flood potential earlier this year. He had passed the Scouts inside the canyon, which he had entered over the protests of rangers.

With his experience and as the manager and lead guide for Zion Rock and Mountain Guides, he had confidence he could examine conditions himself and make a sound decision.

"The ranger said, 'No, I advise you against going; there's a high percent chance of rain,' " Daniels recalled. "I had such a hard time to get the permit, [but I know] they're just doing their job. It's good that they do that."

Daniels had completed Echo before and knew exit routes to get above potential floods. He climbed above the canyon for a view of the sky and predicted no rain would come in the time it would take for him to finish.

He was right.

But he wanted to be sure about the Scouts he had passed.

Eventually, "we saw them come out safely," Daniels said. "There was thunder echoing throughout the canyon. You could have sworn you felt raindrops. It's intense."

For Daniels, making decisions about risk is part of the draw of wilderness. He says denying permits based on the lowest level of canyoneering expertise would unfairly restrict all people who can safely make their own choices.

"It kind of cuts into the free will," Daniels said. "It loses some of its sense of adventure if you have someone saying, 'You can't go, there's a 25 percent chance of rain.' "

Picard agreed.

"Ninety percent of Zion is wilderness," she said. "It's not paved trails. Even on the backpacking routes you are in wilderness. You are alone. Wilderness is managed to be untouched by humans. We work to really get that message across: It's up to every visitor to take responsibility for themselves."

That principle is echoed throughout the National Park Service. But individual parks follow a spectrum of policies guiding risk management in the backcountry. They are strongly connected to each park's unique conditions and hazards but also reflect varying thresholds of risk at which each park will intervene on users' behalf.

At Alaska's Denali National Park — where a peak of 20,310 feet introduces mountaineers to a coveted summit and one of the world's coldest places — rangers deny backcountry permits under virtually no conditions; all backpackers and mountaineers receive a permit if they complete the application process, said park spokeswoman Maureen Gualtieri.

By contrast, Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park refuses backcountry permits when blizzards strike Mauna Loa's 13,679-foot summit, as well as for earthquakes, high tsunami risk, eruptions and "excessive volcanic gas," said park spokeswoman Jessica Ferracane.

At Montana's Glacier National Park, permits may be withheld to backcountry campgrounds if a berry crop there is too profuse, lest visitors and bears find themselves in each other's paths. In Yellowstone and California's Yosemite, rangers said, wildfires often trigger permit suspensions.

—

'Necessary preparedness' • The website for southern Utah's Bryce Canyon National Park notes a backcountry permitting provision that is rare among Western national parks: "Park staff reserves the right to refuse permits to parties that fail to demonstrate the necessary preparedness that Bryce Canyon's high and dry backcountry demands."

Denying permits according to a Zion canyoneer's apparent skill "is where we really start getting into the weeds," Picard said. "Judging people's ability — that's the individual's responsibility."

But Zion's rangers do try to size up canyoneers' skill to make recommendations. When canyoneers redeem their reservations at the visitor center, rangers ask them several questions about their experience, their gear, and their understanding of the risks before permits are issued.

Here again, national parks vary in their approach. While Denali's permit guidelines are the least restrictive, its application process is among the most intensive. A mountaineering permit requires a 60-day wait, a full résumé of each climbers' mountaineering history, a detailed gear inventory, an hourlong PowerPoint presentation and interviews with rangers, Gualtieri said. Simply backpacking at the park requires a 30-minute video and a ranger briefing.

At southeastern Utah's Arches National Park, a permit to hike the Fiery Furnace is issued only after each member of the party checks in with rangers and views a safety video. And at Washington state's Mount Rainier, every member of a climbing party must visit a ranger station to secure a pass.

Meanwhile, Arizona's Grand Canyon National Park issues backcountry permits in advance, via email, with no requirement that any group members contact rangers before they embark on a trek.

At Zion, canyoneers must pick up their permits in person, within a day of their outing — but only the named permit holder in a party must be there. The park often relies on that person to convey all warnings to the rest of the group. That means many of the people in any given slot canyon may have had no contact with rangers. Picard and Zion Superintendent Jeff Bradybaugh said investigators are determining whether the whole Keyhole Canyon group spoke with rangers.

"They could do something like [Wyoming's Grand Teton National Park]," Benson said, "where they make you sit down and watch a video of some sort, have the ranger talk to you — at least that if nothing else."

Picard agreed that contact with an entire canyoneering group is ideal — "We feel better that we've gotten a chance to talk to them and give that information" — but said that a required briefing may play out differently in Zion than in other parks.

While Denali's rangers dealt with about 8,500 visitors through its entire summer season, Zion issued backcountry permits to 9,500 people in June alone, said Zion spokesman David Eaker.

Canyoneers wait up to an hour in line on busy days, Picard said.

"Staff are talking to people all day long about the permit system," Picard said. "We're definitely working hard. It's hard to say whether or not [more required contact] would be feasible."

—

'It's a wild landscape' • As rangers wrap up their investigation into the Keyhole deaths, park officials will begin a "board of review" to evaluate the park's response and policies, Bradybaugh said. Backcountry-permit guidelines will be examined, as will any means to communicate risks to users, he said. Previous reviews have led to other changes, such as relabeling the flood-potential ratings by the NWS, from "dry, low, moderate and high," to "not expected, possible, probable and expected."

"It's a wild landscape and under the influence of nature's processes, so certainly we don't have much control over that," Bradybaugh said. "But where we can employ some different tactics or tools, we're evaluating those."

Permit restrictions for technical canyons were launched in 1998, two years after the National Park Service paid a $1.5 million settlement to the families of two Scout leaders who died during a group trip in 1993 through Kolob Creek.

The slot canyon filled quickly with water after a dam release upstream at Kolob Reservoir. A third adult and five teenage boys survived.

"In the wake of accidents, tragedies, sometimes there is a call for more restrictions," Dunn said. "But I think that's strange because oftentimes the National Park Service is talked down upon for some of the restrictions that they have."

Dunn said he hopes any changes to permits are held up to a broad cost-benefit analysis — and not "just a consequence of what's happening now."