This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

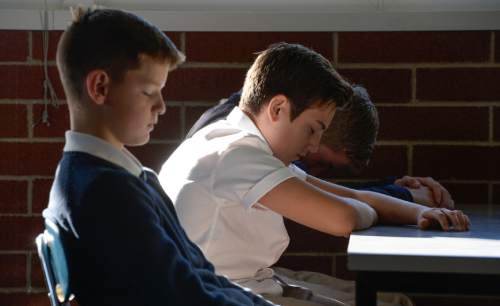

Sandy • Soft sunlight fills the classroom as a mood rarely seen among middle-school students slowly settles in:

Quiet. Calm. Reflective.

Their teacher leads them into part of a new homeroom routine this semester. Bouncy rows of kids fall silent as all relax and start to notice their breathing.

A gentle female voice guides them to invite ease and stillness into their minds and bodies, using a meditation-derived teaching tool called mindfulness that is gaining footholds in Utah classrooms.

Let go of tension, the voice tells students. Be calmed and cleansed with each exhale. As thoughts arise, watch them like kernels of popcorn. Label them as they pop up, then let them go and return to the breath.

The youngsters rest in this way for several minutes before a chime sounds. Eyes open. It's still a Monday at The Waterford School in Sandy.

The class chatters. Students mention homework deadlines. Social pressures. And yet, kids say, they are using this newly cultivated present-moment awareness to help in their everyday lives.

"I was going to freak out," one student said of her busy schedule. But as worry mounted, she remembered to stop, take a breath, observe, and then proceed. "It made me feel better."

—

'Lightbulb moments' • Mindfulness is defined as a mental state reached through awareness of the present moment. Often supported by using breath as an object of concentration, one acknowledges and calmly accepts thoughts, emotions or physical sensations as they arise.

Examples are growing in Utah and across the country of private- and public-school educators bringing these meditation and visualization techniques into classrooms for their therapeutic benefit.

"It's a really important way to help students become more self-regulating and better able to respond in a meaningful and thoughtful way," said Christelle Estrada, instructional specialist with the Utah State Office of Education.

After years of research, Nancy Nebeker, middle-school dean at Waterford, said she sought to make mindfulness part of the small private school's 2015-2016 curriculum in keeping with the year's theme, "The Well-Lived Life," emphasizing curiosity and compassion.

Nebeker discovered that a middle-school parent at Waterford, Becca Peters of Salt Lake City, specializes in promoting mindfulness as a licensed social worker. Nebeker and Peters helped develop a homeroom-based program, with morning meditation sessions three days a week — each lasting from one or two to 10 minutes.

"Mindfulness fits into a much bigger picture," Nebeker said. For one thing, Waterford teachers practice with their students.

"I'm learning along with them," said Latin instructor Christopher Todd.

And though in its early stages, the sessions already appear to be having positive effects.

"You'll see those little lightbulb moments from time to time," Todd said.

English teacher Casey O'Malley has noticed students dealing more effectively with stress.

"You can get to that point if you're a little more aware of your consciousness and feelings," O'Malley said. "But you need to work for those moments. They're not going to come to you naturally."

Peters, whose daughter attends Waterford, is also founder of Metta Mindfulness Center in downtown Salt Lake City, where she works as a mindfulness educator, consultant and clinical social worker in private practice.

"Mindfulness is not a quick fix," the UCLA and Stanford-trained counselor said. "It is a way of living that deepens over time.

"It is my hope," Peters added, "that students will find a sense of ease, calm and self-compassion through the practices of mindfulness and meditation and will learn through self-reflection that there is always a choice to direct kindness toward themselves and others."

—

Mainstreaming mindfulness • Mindfulness as a practice is thousands of years old.

Common to all Buddhist traditions, the meditation technique known as "shamatha" or "calm-abiding" is widely used today in schools, hospitals and other settings to promote health and well-being, without religious connotation.

Hard evidence is still accumulating on the academic and social benefits of mindfulness in the classroom as more programs take hold. Anecdotally, educators report that short, daily meditations seem to enhance students' attention spans, sense of compassion, resilience and self-control.

"The results," Estrada said, "are having a huge impact on schools."

Mindfulness instruction has surfaced off and on in Utah for several decades, she said, often borne of teachers' own personal experiences.

Renowned professor of medicine and stress-reduction researcher Jon Kabat-Zinn — credited by some with coining the term "mindfulness" in the 1970s — has said his first encounter with a teacher trying to integrate it into her classroom was in Utah more than 20 years ago.

The public elementary school instructor, Kabat-Zinn recalled, personally benefited from mindfulness-based stress-reduction at an area hospital.

"Back then, there was no larger movement among educators aimed at bringing mindfulness into the mainstream of public and private education," Kabat-Zinn recently wrote. "People hardly even knew the term mindfulness, never mind what it meant."

Today, Kabat-Zinn is an adviser to Mindful Schools, an Oakland-based network of educators promoting mindfulness curriculums, online training and professional support for would-be pioneers.

Since its founding in 2007, the group has trained teachers nationally and abroad, with an estimated impact on up to 300,000 students. Many of Utah's mindfulness instructors draw on its resources and research.

In a 2011-2012 study done in cooperation with University of California, Davis, Mindful Schools compared students who meditated an average of eight minutes per school day for six weeks with those in a nonmeditating control group. The study found marked improvements among meditating students in attention, participation and showing care for self and others.

Mindfulness also addresses what the group calls "toxic stress" in which daily demands on students, parents or teachers regularly outpace their ability to cope.

—

Goodbye, stress; hello, calm • By the time students reach Jason Tackett's behavior-support unit at Franklin Elementary School on Salt Lake City's west side, they usually have faced plenty of stress from trauma, abandonment and other problems. Tackett sought formal training in mindfulness earlier this year and introduced it to his students after experiencing what the practice meant in his own life.

"Being on the go all the time," he said, "I found I just needed those moments to slow down."

After regular mindfulness sessions of five to 15 minutes, Tackett said, he has seen improvements in how his fourth-, fifth- and sixth-graders deal with anger, anxiety while taking tests, and even bullying.

"It helps them have that deeper focus," said Tackett, selected in 2015 as a Utah Special-Education Teacher of the Year. "They are very receptive to it."

He calls it "empowering" to encourage students to contemplate their own minds after a lifetime of having others tell them what to do.

"It turns them back to their own information," Tackett said. "It's not trying to change their experience. It's more like, working with their experience."

These days, as Tackett wheels a cart laden with meditation cushions through school hallways, students "react with anticipation. They get really excited about it."

Peters, the mindfulness counselor, calls it a gift to students and teachers alike.

"They are co-learners and will experience the benefits together," she said. "It is an investment of time and resources worth making."

Twitter: @TonySemerad