This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note • In this regular series, The Salt Lake Tribune explores the once-favorite places of Utahns, from restaurants to recreation to retail.

Tears flow easily whenever Tina Parsons remembers Bill and Nada's, the much-missed Salt Lake City cafe that once stood at 479 S. 600 East. The site is now a Smith's gas station.

"I drive by that Smith's now, but it's very difficult because I know what was there," Parsons says, her eyes welling up. "Now it's just ... ghosts."

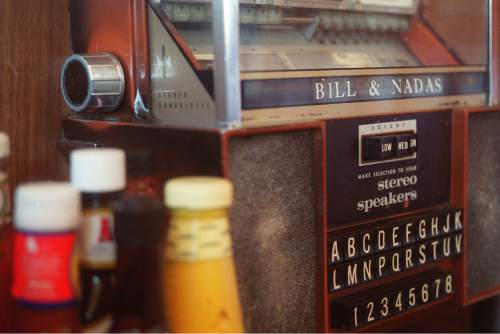

Ghosts and memories. Of the tableside jukeboxes stocked with vintage country tunes. Of the Naugahyde seats and simulated wood-grain tables. Of the WHERE THE HELL IS BILL AND NADA'S? T-shirts and the paper place mats with the U.S. presidents. Of the spinning prize wheel, which, if it landed on your table number, would provide a free meal. Of the Big Bill sandwich, the orange pancakes and the most famous (and likely least-ordered) menu item of all: calf brains and eggs.

"Everybody I knew ate the brains and eggs," Parsons recalls. "They were good, but a little slimy, and you had to chew them. People would eat them on a dare. Most were either really high or really drunk when they ordered them."

Former Gov. Jon Huntsman Jr. was a Bill and Nada's regular in the 1970s. He was known for keeping a painting of the cafe in his office during his time in the Utah Capitol.

"It's one of my cherished possessions," he says.

Though Huntsman never had the courage to consume the sauteed cerebrum, he knows people who did.

"It upped their status in town considerably," he says.

—

Everyone welcome • The "Bizarre Foods"-worthy dish was just one aspect of the cafe that made it so appealing. The time-trapped decor and eau de greaseball aroma created an environment Tom Waits or Charles Bukowski would've felt comfy in, one that earned fans with all kinds of backgrounds, from blue-collar Utah Power & Light workers who needed a place to eat at 3 a.m., to business executives grabbing breakfast before an important meeting, to kids like Parsons and her friends — mohawked '70s punk rockers who needed a place where they wouldn't be judged.

"At that time, there were still places in town that had PUNKS NOT ALLOWED signs in their doors," Parsons says. "We would go there at 1:30 in the morning and wouldn't walk out until 2 in the afternoon, and the waitresses never said a word. It gave kids who got kicked out of their house a safe place to go."

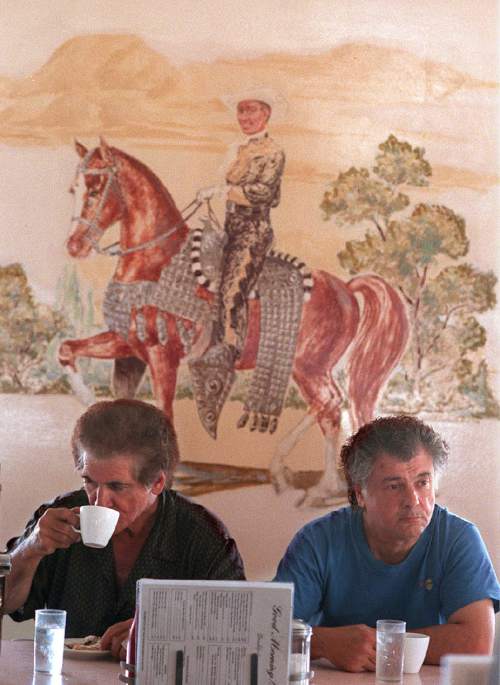

"The crowd was a combination of artsy hipsters, washed-up rock musicians, which I would count myself one, and truckers working the night shift," Huntsman remembers. "Everything was always in motion. I remember watching a column of ants marching from a morsel of food in the middle of the floor straight up the wall."

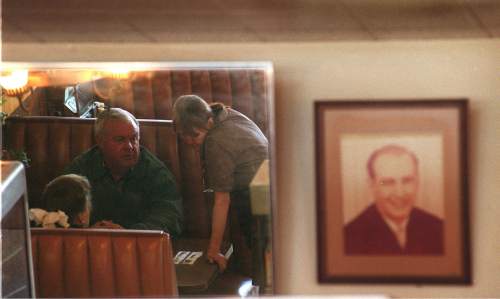

Opened in 1946 by Bill McHenry and his wife, Nada — pronounced NAH-duh, not NAY-duh, and apparently you would've incurred Bill's wrath if you incorrectly pronounced it — the couple ran the 24-hour diner steadily until 1962, when Nada died. As a tribute, Bill never changed the cafe's name and never removed her portrait that hung on an inside wall.

McHenry was an avid horseman and rode in numerous Days of '47 parades, which is how he met Ellen Rawlins, whom he married the same year Nada died. Two years later, he hired Maxine Young as a waitress, and eventually she was put in charge of handling the cafe's finances.

"Ellen never dabbled in the cafe; that was Maxine," says Jolyn McKee, Bill and Ellen's granddaughter, who waitressed at the cafe for more than 20 years, as did Earline "Chipper" Young, Maxine's daughter.

"Maxine took over Nada's place, and she became a really big part of it," Young says. "Without Maxine, the business would have died. Bill would've ran it into the ground. He didn't have the personality to keep it going after Nada."

As waitresses, McKee and Young remember the bar people who wandered in drunk at 2 a.m. and were always the best tippers, and the Mormon men who wouldn't drink coffee if they were with their wives but would if they were alone. Many customers remember the family feel of dining there, but for the two women, the feeling was literal.

"My brothers cooked there," Young says, "my sisters waitressed there, cousins worked there, our kids were raised there."

—

A jealous rage • One night in 1969, family became a little too intertwined when Maxine's husband and Young's father, Earl Young, entered the cafe and shot Bill five times, convinced that he and Maxine were having a relationship a tad steamier than a mere plate of brains and eggs. Somehow, Bill survived.

"I was a preteen when it happened," McKee says. "I was told that he went in the restaurant in a jealous rage and shot Bill because Maxine was working so many hours."

"Mom picks up the gun and calls the cops," Young recalls. "I was only 5 or 6. The police came and got me in the middle of the night from my dad's house, and he went to prison for five years, then went on with his life. But when my dad was dying, my mom did go see him, and she forgave him."

So, were Bill and Maxine really having an affair?

The short answer, according to McKee and Young, is yes.

"Half the customers knew, everybody knew," Young says.

"But nobody would talk about it," McKee adds. "So Maxine was the business partner and Ellen was the wife. And they made it work."

"It was almost like Bill, Ellen and Maxine were one family," Young says. "Bill and Ellen lived across the street from the cafe, and my mom lived right next door behind them in a duplex. And every night at 5 p.m., the three of them would eat together at the cafe."

—

A death in the family • In August 1999, Bill and Ellen died of cancer just three weeks apart. It was the beginning of the end for the cafe. Maxine tried to keep things running, but managing an all-night eatery proved too difficult. The cafe closed forever Dec. 22.

"Bill passed first, and I moved in with Ellen to take care of her," McKee says. "She had dementia and would wake up every morning asking about Bill. We would say he's at the cafe. Then she would remember he had died, and she would just sit on the stairs and cry. In some ways, it was a blessing that she went so quickly after Bill."

"I thought about buying it," Young says, "but mom told me the pipes were so old and that I'd be getting into a can of worms, so she talked me out of it. But I really considered it and regret it every day of my life that I didn't. Our families were all part of it, but now we've all spread out and we don't keep in touch. It's been a big hole in my heart. I even thought about trying to rebuild it."

The building stood for a couple of years, until it eventually was bulldozed. It remained a vacant lot until Smith's turned it into a gas station.

"I stayed home and cried when they tore it down," McKee says. "I couldn't even drive past it for three or four years."

"Even after the punk scene faded and everyone got older, we would still meet at Bill and Nada's," Parsons says. "When it closed, that's when we lost contact with each other. The day it was torn down, we all sat across the street and watched. It felt like losing a family member."

Bill and Nada's was so influential in Parson's life that it helped her decide to go into social work. She currently works with autistic people.

"The hard thing is, we never thanked Bill and his family for what they gave us, because we were punk and had this facade to show, we had to be something else," Parsons says. "But Bill and Nada's saved a lot of us. I think more of us would've died had it not been for Bill and Nada's. A lot of us were runaways and street people in that movement, and that place was the only thing we had, and now we're all doctors, lawyers and dentists. People evolved into something better, and Bill and Nada's played a huge part in that.

"But as hard as it was when they tore it down, I think it was the right time. It would've faded and it would've turned into something it was never supposed to be. For all its imperfections, it was perfect."

Maxine died in 2005. And neither Parsons, McKee nor Young ever has bought gas at that Smith's station.

If you have a spot you'd like us to explore, email whateverhappenedto@sltrib.com with your ideas.