This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

LDS Church guidelines that exclude gay couples and their children from some Mormon rituals may be official, but these new rules are not necessarily divinely endorsed — and could easily change.

That's because these instructions for lay leaders in the Utah-based faith are defined as a "policy," not a "doctrine," a distinction even many in the 15 million-member Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints don't fully grasp.

Doctrines remain fairly constant, while policies are revised, updated and tweaked as circumstances arise.

Here's how Patrick Q. Mason, head of Mormon Studies at Claremont Graduate University in Southern California, describes the relationship between the two:

"Mormonism has a set of theological principles, which crystallize into particular doctrines, then are implemented and enforced through a series of policies."

A policy, Mason explains in an interview, "becomes the administrative fleshing out of the church's doctrines."

Still, the line between the two can be blurry and difficult to distinguish.

Perhaps the most significant historic example was the LDS Church's longstanding priesthood and temple restriction on black Mormons.

For decades, Mormon leaders defended the ban as "doctrine," believed to be based in scripture and theology.

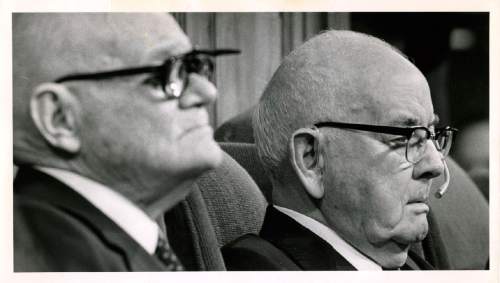

In the 1960s, though, then-LDS Church President David O. McKay began to tell friends "the church position on ordination of blacks was 'policy,' not 'doctrine,' " writes Gregory Prince in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, "and that the practice someday would be changed."

The difference between the terms was "crucial" to McKay, Prince explains. "To him, a policy could be changed, albeit in this case only upon receipt of a revelation, whereas a doctrine could not be changed."

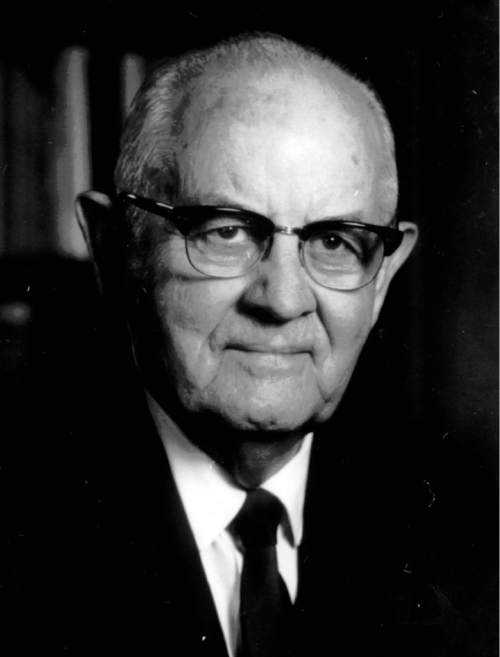

By altering the language, it gave LDS leaders a new way to think about the ban, opening the door for its eventual end in 1978 based on what Mormons believe was a revelation from God to then-President Spencer W. Kimball.

Policies are spelled out in places such as the two- volume Handbook, which guides members and local leaders on such significant topics as when church discipline is mandatory, who is eligible to enter one of the faith's temples, how to "cancel a sealing" (or get a "temple divorce," as it is commonly known), and the duties of various male and female leaders.

The latest Handbook describes church positions on contemporary issues. For example, the faith opposes gambling (including government-run lotteries), guns in churches, euthanasia, Satan worship and hypnotism for entertainment.

It "strongly discourages" surrogate motherhood, sperm donation, surgical sterilizations (including vasectomies) as forms of birth control, and artificial insemination — when "using semen from anyone but the husband." It supports organ donation, paying income taxes, members running for political office and autopsies — "if the family of the deceased gives consent."

Doctrine dictates that members meet together in congregations, but policies about how those wards and branches are organized have varied through the years. Most Mormons worship with neighbors within certain geographical boundaries, but some are joined together by language, ethnicity, marital status or military service.

The LDS Church's descriptions of homosexuality have evolved through the years from a sinful perversion to a recognized and unchosen attraction. Today, the faith doesn't consider being gay a sin, only acting on it is.

Mormon doctrine teaches that marriage is exclusively between a man and a woman, so the church has steadfastly opposed same-sex marriage. The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in June to legalize gay marriage across the nation left the church wrestling with what to do about its legally married gay members.

Last week, LDS leaders changed Handbook 1 to say that gay couples — either married or cohabiting — are "apostates," and children whose parents are or have been in same-sex relationships cannot participate in blessing or baptism rituals. They must wait until they are 18 before they can seek approval from the faith's governing First Presidency to join the LDS Church.

Mason, the historian, cautions members to remember that this is a policy, not a doctrine.

In fact, Mormon apostle D. Todd Christofferson, in a video explaining the new rules, refers several times to the guidelines as a policy.

"I have seen and heard nothing from the church stating that this policy came by revelation," Mason writes on Facebook, "nor are we asked to sustain it as such. We are never asked to sustain the Handbooks."

Policies, he adds, "come and go."

"Most of them are good and sensible," Mason says, "some of them are lame, misguided and even hurtful. As people of conscience, we are always within our rights to disagree with anything within the church, but especially policies. We can responsibly say to ourselves, to our friends and neighbors, to our fellow church members and to our priesthood leaders, 'I sustain my church leaders as men (and women) called by God and striving to lead his church by inspiration, but I do not agree with this policy of the church.' "

Many Mormons are calling on their church leaders to modify this new policy on same-sex couples — particularly the limitations affecting the children — and soon.

If podcaster John Dehlin's source is correct, that may happen.

On Wednesday, Dehlin, the excommunicated Mormon who divulged the Handbook 1 changes to the media last week, claimed he had reports that the LDS Presidency of the Seventy sent out a memo to regional leaders, saying that "there will be additional clarification on these changes from the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve [Apostles] in the coming days."

When asked for confirmation, LDS Church spokesman Eric Hawkins "declined to comment."

Twitter: @religiongal