This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Spanish Fork • In 1608, John Smith published "A True Relation of Virginia," describing the settlers of Jamestown and their experiences with the native tribes.

Sixteen years later, Smith published "The Generall Historie of Virginia," which, among other revisions, included the now-famous account of Pocahontas intervening to save Smith's life from execution by her father, Powhatan.

In the 400 years since their publications, the discrepancies between Smith's Jamestown accounts have puzzled historians, including students at Utah's Diamond Fork Junior High, who in late November debated conflicting interpretations of the Pocahontas scene.

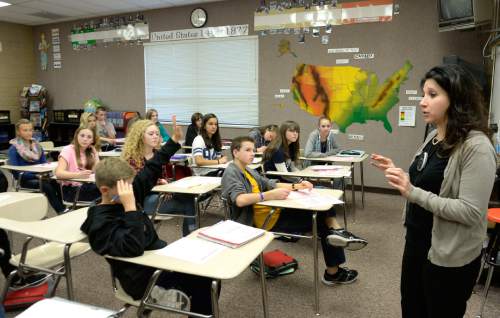

Debate and discussion are the classroom style of social studies teacher Kelly Cole, who emphasizes analytical skill over the memorization of people, places and events.

"They become real critics," Cole said of her students at the Spanish Fork school. "They start to recognize faults in adults, which is pretty fun to see."

More of Utah's history classrooms soon may resemble Cole's, with teachers asking students to compare, critique and defend historical accounts rather than memorize the number of stars and stripes on the U.S. flag. For the past two years, Cole has been part of a writing team working on an update to Utah's secondary social studies standards, which outline what students are expected to learn between seventh grade and their senior year. In Utah, this includes a full year of lessons on the Beehive State in addition to world and U.S. history. Currently, the seventh-grade Utah Studies curriculum doesn't go past the 19th century.

"The goal," Cole said, "was to really try to bring Utah Studies out of just Native Americans and mountain men and pioneers."

Utahns should get their first look at the proposed changes in December. The writing team is set to deliver its work to the state school board this week; if all goes as planned, the board then will release the standards for a 90-day public review.

But statewide standards are a lightning rod for controversy, prone to accusations of political bias and national agendas.

And history education is already in the crosshairs. Last year, the Advanced Placement U.S. History exam was revised to a skills-based format, like the proposed Utah standards, resulting in accusations that test administrators had focused on negative, anti-American events.

Teachers cannot cover everything, said Brigham Young University associate professor Jeff Nokes, and a shift to a skills-based approach comes at the expense of content.

But content knowledge is fleeting, he said, and an argument about which Founding Father or U.S. war merits the most class time ignores the fact that students will not remember who did what, when or where.

"Those debates," Nokes said, "are largely an argument in what we want our students to forget."

A better approach, according to Cole, is to educate with an eye toward the kind of thinking students will be expected to do as adults.

When a quick Internet search brings up the full text of the U.S. Constitution, Cole said, forcing students recite the preamble may not make as much of an impact as empowering them to reach educated decisions on a ballot.

"It's great to memorize facts for Jay Leno," Cole said. "But if they don't go out and vote or take an active part in society, then we've failed them."

—

Civic engagement • If approved, the new standards would be the first major overhaul of social studies education since 2002, according to Robert Austin, a social studies specialist with the Utah Office of Education. But the proposal won't change classroom content as much as it will change how that content is presented.

"A geographer doesn't come home from work and say, 'My hand is so tired, I colored 50 maps today,' " Austin said. "That's the shift. How can we promote the doing of social studies?"

The language of the new standards expects students to draw their own conclusion on social studies topics, Austin said, and to support them with evidence.

There's also an increased emphasis on preparing students for civic lives, he said.

"We talk a lot about wanting to make sure kids are college- and career-ready," Austin said. "We also want kids to be civically ready and to be civically engaged."

Nokes said civic education is what "put social studies on the map," and helping students develop analytical research skills promotes historical literacy and critical thinking.

"There is a need to prepare young people to be part of our great republic," Nokes said, "and they're probably not going to develop those skills in English or math to the same degree that they'll develop those skills in social studies."

Whereas a traditional history class might ask students to list the freedoms included in the U.S. Constitution, Austin said, the new standards would encourage students to explain the role constitutional ideas had in the civil-rights movement or play in the current debates about religious freedom.

"Most teachers try to connect the dots," Austin said, "and that's really where the magic happens in the classroom."

—

Modern times • In addition to updating U.S. history classes, the way Utah children learn about the Beehive State's history would also change under the new standards.

That would mean lessons on time periods that have been largely uncovered: the 20th and even 21st centuries.

Under the proposal, Utah history is divided into five periods: from prehistory to the Mormon settlers, from settlement to statehood, from statehood through the World Wars, postwar Utah through the 2002 Winter Olympics and, finally, contemporary Utah.

Teachers would have autonomy to approach those content areas, Nokes said, but would be expected to give roughly equal class time to each period.

"We should be well beyond the pioneer era halfway through the course," Nokes said.

But unlike math, English and science, there is no statewide history test at year's end pushing teachers to cover every subject.

That allows teachers flexibility in planning their lessons, Nokes said, but also removes a check on whether Utah history classes are moving beyond Brigham Young's "this is the right place" proclamation in 1847.

"We can write the standards but whether or not teachers follow the standards is a different issue," he said. "We teach the way we were taught. It takes a while to break out of those traditions."

—

Utah standards • If recent experience is any indication, the new social studies standards will not be challenged for what they contain, but rather for what they leave out.

When the College Board updated its framework for the AP U.S. History test last year, critics claimed that the Founding Fathers, free-market capitalism and American exceptionalism were either downplayed or erased altogether.

The framework was updated again in July, with specific references to the founders and free enterprise.

In drafting the Utah standards, Cole said, the writing team largely avoided lists of required topics, because any list inevitably leaves out someone or something important.

"Obviously if you get through U.S. history and don't learn about George Washington," she said, "that would be tragic."

Parents shouldn't see the presence or absence of a particular subject in the standards as prescriptive, Nokes said.

He said the goal is to move away from timeline-based courses, filled with memorization of dates and names, and give teachers the ultimate say over what topics are covered.

"We don't want to just have heritage classes," Nokes said. "History is a discipline, and there are ways of thinking about evidence and working with it that I think are important in today's day and age."

Austin said there's a need to move away from a paradigm that focuses on covering historical events.

"The irony is that to cover means to conceal," Austin said. "Why don't we uncover and help kids discover?"

The 90-day review period includes a request for public input on the standards, and Austin said that feedback is crucial to preparing a final draft of the new standards.

Unlike recent changes to Utah's English, math and science standards, which are criticized for their similarity to standards developed outside the state, there is no set of national history benchmarks from which to draw.

"These are Utah standards," Austin said. "We have Utah people making these standards and we want them to be the best standards possible."

Twitter: @bjaminwood