This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

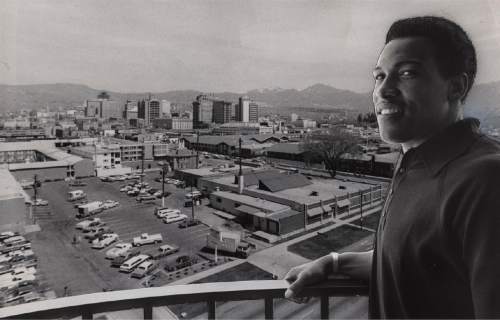

He was barely 20, still quiet but with flashes of potential that hinted at the Hall of Fame career ahead of him. He had a million-dollar contract but no car. He was injured and suddenly out of work. So on the day the Utah Stars folded, Moses Malone walked with a limp as he pushed a cart piled high with jerseys, sneakers and red, white and blue basketballs down West Temple to his hotel.

It is to this day one of the lasting memories of the demise of the only professional basketball team in Utah to have ever won a championship. And for the players who lived it, it feels like there are ever fewer of those.

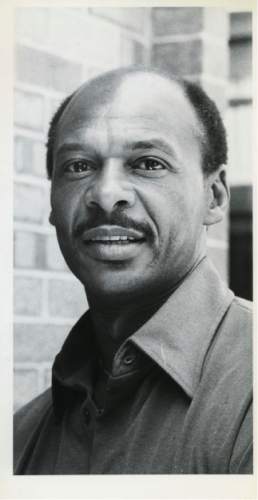

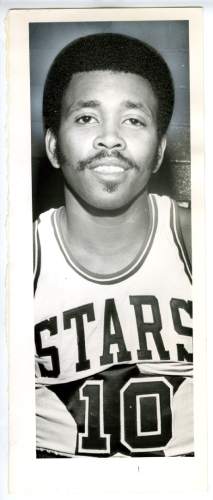

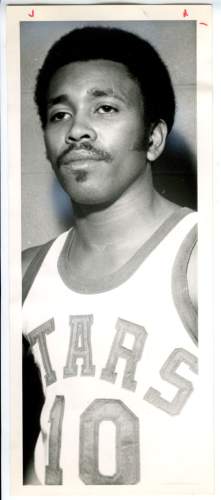

"There really isn't much [sense of history] and it's too bad because Salt Lake City was introduced to pro basketball with that franchise," said Ron Boone, the Stars' ironman guard who played 1,041 straight games over his ABA and NBA career.

But it has been 40 years now since the day the Stars went out in Utah. The upstart and underfunded American Basketball Association that popularized the 3-point shot and introduced the world to legends like Julius Irving, George Gervin and Malone folded, too, the following spring. That anniversary and a spate of deaths has brought memories flooding back to the people who lived them.

"I started thinking about it this last summer after so many guys were passing," Boone said.

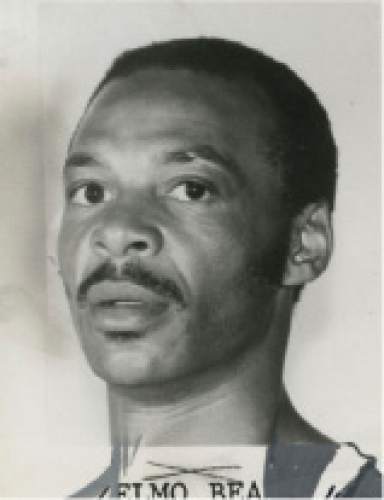

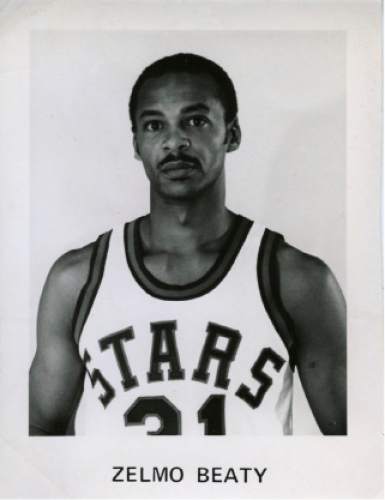

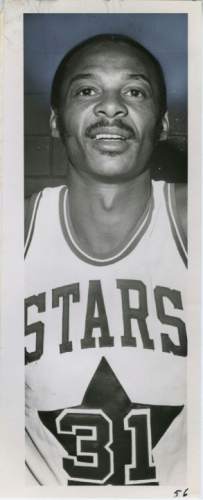

Stars great Red Robbins died in 2009. Merv Jackson in the summer of 2012. Zelmo Beaty in August 2013.

Then, last September, Malone died at the age of 60.

"It was heartbreaking," said former Stars forward Ken Gardner.

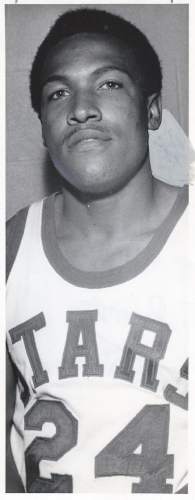

At 19, the 6-foot-10 Malone shocked the basketball world by jumping from high school to the pros, signing what was then a massive deal with the Stars worth a reported $3 million over seven years. He was still an awkward kid from Virginia when he arrived in Salt Lake. He mumbled and talked with his head down around his teammates.

But on the court, Malone was a prodigy.

"Moses was so quick he'd go up and down twice before everybody else jumped once," Gardner said.

But Malone's ABA career was almost as quick — he started with the Stars in '74.

Gardner had played three years in France after finishing a collegiate career at the University of Utah. But in the summer of 1975, he tried out and earned a roster spot on the Stars roster.

"A slow, 6-5, non-jumping white kid from Clearfield and I make the Stars," Gardner recalled recently. "It was my big break in the pros. Turns out, my big break was the year they folded."

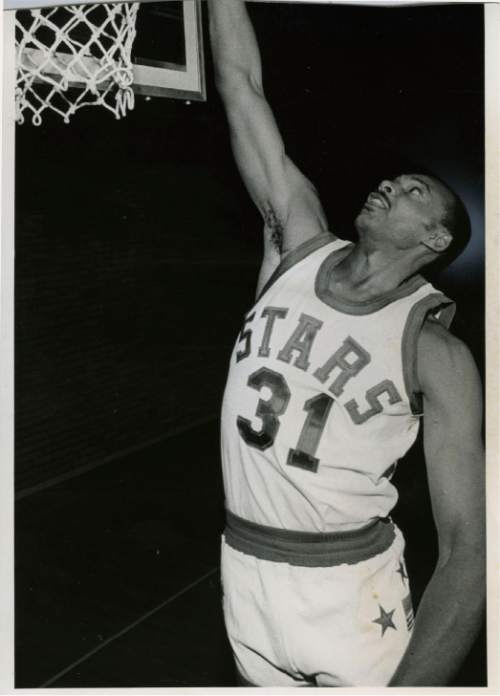

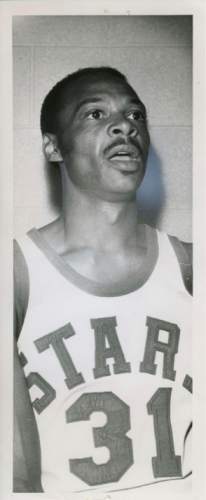

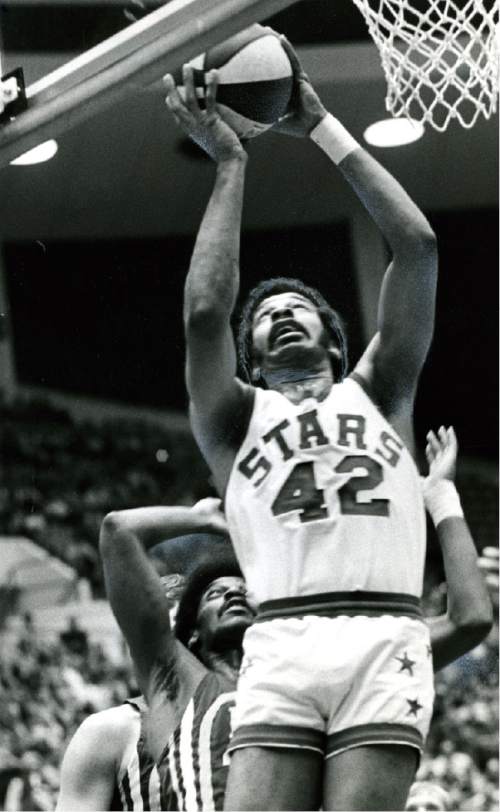

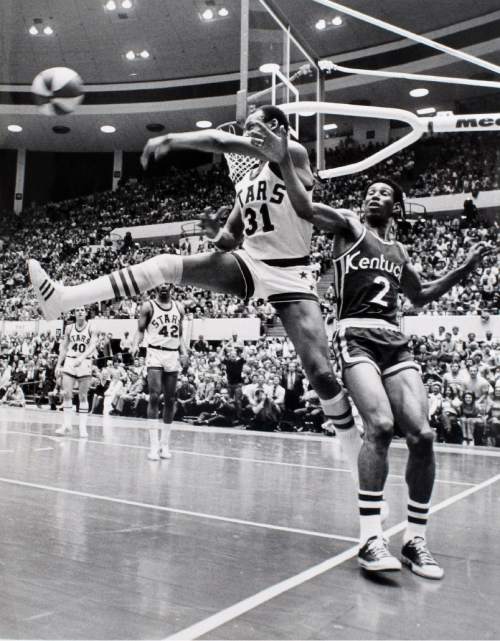

In 1971, behind the talents of Boone, Beatty and Willie Wise, the Stars had brought Utah a taste of glory, beating the Kentucky Colonels in seven games to claim the ABA title.

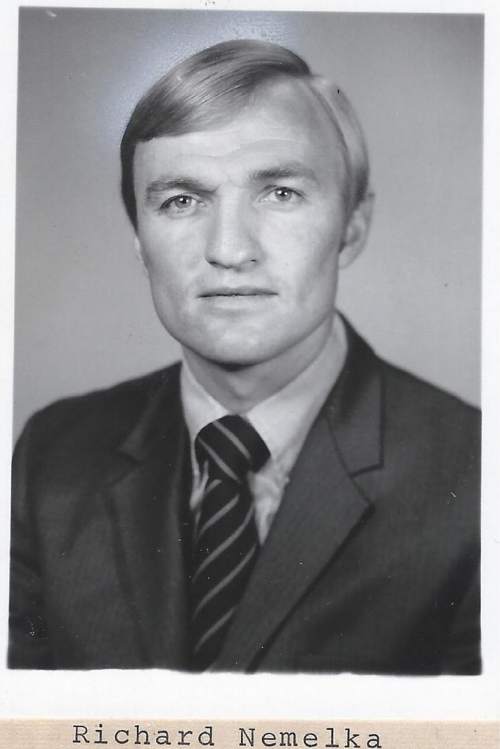

"When we came back from Kentucky [after a Game 6 loss] it was amazing how many people were at the airport to greet the team," said former Stars guard Dick Nemelka, who had been an All-American at BYU but couldn't make a team in the NBA after returning home from a two-year LDS mission. But after a tryout arranged by his West High basketball coach, Nemelka found himself back on the court and in his hometown in 1971 when fans rushed the floor at the Salt Palace to celebrate the team's title. "The atmosphere was electric."

But by the winter of 1975, things were very different.

Owner Bill Daniels, whose cable TV fortune allowed him to buy the Stars in 1980 and move them from Los Angeles to small-market Utah, was out of cash.

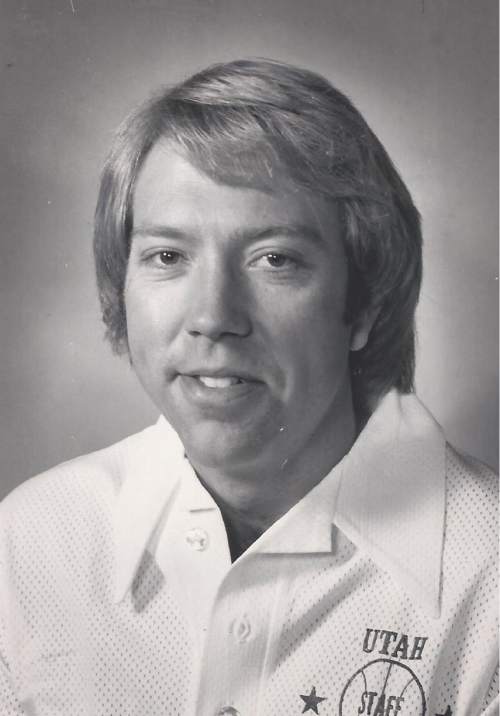

"Bill Daniels would have been a great owner," former Stars and Jazz coach Tom Nissalke said, "but he had no money."

The Stars and the Spirits of St. Louis would merge. Nissalke figured Salt Lake would be the better market for basketball and the teams would join forces there.

"Of course, it didn't turn out that way," he said.

On Dec. 2, 1975 — 40 years ago this month — the Stars folded.

"The NBA desperately wanted those young players," the coach said.

One of those talents was Malone, who would go on to be named the NBA's MVP three times over. But in 1975, Malone was out with a foot injury and the Stars were 4-12 to start the year.

"Had we had him, that would have put a different look on the Stars that next year," Nissalke said. "It think had Moses been able to play, I think Utah would have been able to keep the Stars. That's how I see it now."

Broke and out of options 16 games into that season, however, Daniels announced to his team at a shootaround that the Stars were folding.

"He was holding a half bottle of Cutty Sark Scotch. His eyes were red and you knew he was having a hard time," recalled former Stars trainer Bill Bean.

The next spring, the ABA was finished too. But the players who were there believe it left its mark on the game and on this city.

"It really catapulted the NBA to the success it started to have," Boone said.

The NBA's old guard may have been slow to embrace what made the ABA great. But the once physical and plodding NBA has, over the years, slowly accepted some of those tenets.

"There was more style to it," Nemelka said. "Steph Curry's bringing that back."

Said Boone, a longtime radio and TV analyst for the Jazz, "You're starting to witness ABA basketball from years ago with the transition game, because we did run. We introduced the 3-point shot to the rest of the world. Even when the NBA adopted the 3-point shot it was not used the way the ABA used it. They used it in desperation when they need a 3 to tie the game."

Now the 3-point shot has revolutionized the game.

So as Boone and his former teammates watch the Utah Jazz each night, they can't help but think of the impact the Stars had here.

"It kind of paved the way later on for the Jazz," said Nemelka. "I don't think the Jazz would have come to Salt Lake had they not seen the track record of the Stars and how popular they were. It kind of set the town for a professional sports team to stay in Salt Lake."

This month, as they've reflected back on the anniversary of the Stars' end, former players have mourned Malone's passing while chuckling at the memory of his walk from the Salt Palace to the old Tri-Arc hotel.

Years after the team had gone bankrupt, Daniels made back his fortune and tried to make financial amends to coaches, players and season-ticket holders. But that day in 1975, there were no paychecks coming. So Nissalke told Bean to open up the equipment closet in the locker room.

"I remember we just cleaned that whole thing out," Gardner said. "We took shoes and our uniforms and socks and jocks and some of these warmups from the 1971 ABA champs."

Malone, as they tell it, took the most — including Boone's jersey.

"He had that cart loaded down with equipment," Nissalke said.

Boone was not with his teammates that morning. Malone joked for years that if he wanted his jersey back, he could buy it from him.

"I still haven't gotten that jersey," Boone said. "I talked to him about it and he said it was in his mother's attic in Virginia. He said it was there; he didn't say he was giving it back."

Over the years, items from that closet have been sold and lost, boxed up and forgotten. Other reminders have faded, too.

The street that was once "Stars Avenue" downtown had its name changed back to 100 South. The championship banner that once hung in the Delta Center has come down too.

"You kind of understood where they were coming from," Boone said. "They wanted to develop their own identity."

But the players who lived it would like for those memories to live on in some way or another.

"Who knows?" Boone said. "It might be the only championship that the city will see."

Twitter: @tribjazz