This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Jan. 28, 1986, was a chilly day in Utah, with a low of 18 degrees in Brigham City. That's also about how cold it had dipped to overnight at Cape Canaveral, Fla., where the Space Shuttle Challenger was sitting on the launch pad.

An eager crowd gathered there while students from around the nation were herded before TV screens to see New Hampshire's Christa McAuliffe become the first teacher in space.

None knew that a Utah group of engineers from Morton Thiokol Inc., maker of the booster rocket motors attached to the shuttle's external fuel tank, had recommended against the launch because of the cold temperatures in Florida.

With their warning rescinded by their bosses, under pressure from NASA, some of the engineers feared Challenger might explode on the launch pad.

It didn't. It blew up 73 seconds into flight.

The tragedy 30 years ago today stunned the nation and the legions of children who were watching as the seven crew members died.

Investigations began immediately, and President Ronald Reagan appointed the Rogers Commission to sort out the mistakes. Soon, much of the focus would shift to Utah, to the booster rockets and to the engineers who had recommended against launch, and why they were overruled.

For some, the disaster still reverberates.

—

'Catastrophe of the highest order' • Morton Thiokol's aerospace division won a 1974 contract to manufacture the shuttle booster rockets, and it built a test facility in the remote desert north of the Great Salt Lake near Brigham City. By 1986, the division employed a Utah workforce of about 4,000 employees.

The booster rockets were built in sections that held aluminum-based fuels above the motors. The section joints were sealed by huge primary O-rings and secondary ones in case the main seal failed. Before Challenger's explosion, there had been 24 successful shuttle launches and landings.

But Ogden resident Allan McDonald, director of Morton Thiokol's booster-motors program, said all was not well even before the 1986 launch.

In January 1985, company engineers found a large quantity of black soot in the O-rings of the recovered boosters that had helped launch the Discovery. It was the first time they had found black soot in the rings, indicating seal leakage, said McDonald, who retired in 2001.

Engineers concluded that the only difference from previous launches had been the air temperature: 53 degrees, or the lowest ever up to that time. The temperature had dropped into the teens for three nights before that launch.

That prompted Roger Boisjoly, Morton Thiokol's O-ring expert in Utah, to write a memo to NASA, saying he believed the O-ring seals could fail in freezing temperatures.

"The result could be a catastrophe of the highest order — the loss of human life," he wrote.

—

'There's a cliff out there' • A year later, meteorologists were predicting the temperature at Cape Canaveral could fall to the high teens early on the morning before Challenger's launch. Engineers in Utah convened and talked by phone with McDonald, who was at the launch site, and NASA officials from Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala.

Robert Lund, Morton Thiokol's vice president of engineering, recommended that NASA not launch if the temperature was below 53 degrees.

"I couldn't believe the reaction of the NASA people at that time," McDonald said recently. "They said, 'We don't think you can make such a restriction on the shuttle with what you've presented here. You don't have hard test data that shows that's the temperature you can't launch below.' "

Boisjoly, who died in 2012, told NASA officials: "There's a cliff out there someplace — that it will not seal," according to McDonald.

At that point, NASA manager Lawrence Mulloy pressed Joe Kilminster, Morton Thiokol's vice president of the space booster program. Kilminster convened a meeting in Utah, during which Lund was pressured into changing his decision. Returning to the telephone conference, Kilminster reversed the engineers' recommendation.

NASA wanted the decision in writing, signed by a Morton Thiokol official. McDonald declined.

"I made the smartest decision I ever made in my life," he said. "I refused to sign it."

Instead, Kilminster signed the document and faxed it from Utah. The launch was on.

—

A pioneer teacher • McAuliffe made Challenger's mission different from all previous U.S. space flights.

Educators from all states and U.S. territories had applied for the Teacher in Space program that began in 1984. In Utah, 10 were named as finalists and two — Park City High teacher Linda Preston and John Barainca, a teacher at Brighton High — were chosen to compete in Washington, D.C., in summer 1985.

Barainca died last year. Preston, now retired and living in Colorado, said she didn't think Utah's teachers had much of a chance of securing a seat — because one of Utah's U.S. senators, Jake Garn, had flown on a shuttle in April 1985.

As a finalist, Preston went to Florida for the launch. But when delays postponed it, she had to return to Park City and her classroom, where she was on Jan. 28.

Park City schools did not have cable television in classrooms, but the school principal pulled her out of class. They went to his office and watched replays.

"I had met five of the seven people who were on that shuttle," Preston said by telephone. "I was devastated."

Former U.S. Rep. Jim Hansen, who represented Utah's northern district where Morton Thiokol was located, said he was in his Capitol Hill office.

"Two staffers came running in and said, 'Congressman, turn on your TV. The Challenger just exploded,' " Hansen, now 83, said recently. "It was a devastating thing to occur."

For Garn, the death of the astronauts was personal. "Some of them I had trained with," he said.

State Sen. Peter Knudson, who in 1986 was mayor of Brigham City, was at his orthodontics practice when he saw on the news that Challenger had exploded.

"Immediately I thought of all the people in Brigham City who at that time were either engaged as employees or were members of management at Thiokol," he said. "I knew so many of them. I thought, 'Oh my gosh, this is horrible.' "

—

'This commission should know' • At the control center, McDonald "was totally shocked like everyone else," he said. "But at the time, I didn't believe it was the solid rocket boosters. In fact, I convinced myself the only thing that did not fail was the solid rockets."

As part of a NASA "failure team," he went to Alabama and viewed evidence from films and other data. He concluded that the O-rings had failed because of the cold weather, and that the temperature, along with other factors, caused the rocket motors to leak flames that in turn ignited the external fuel tank.

Some NASA officials tried to keep a lid on the pre-launch warning by the Morton Thiokol engineers.

After a memo that was leaked to The New York Times pointed out their concerns, McDonald said, he was sent to Washington to brief NASA officials about his conclusions.

But he was initially kept from testifying before the Rogers Commission, led by William P. Rogers, the former secretary of state, and Vice Chairman Neil Armstrong.

Instead, Mulloy, the NASA official who had pushed to launch Challenger, was responding to questions about whether a contractor had recommended against the launch.

McDonald said he walked down the stairs in the auditorium to get nearer to commission members and said, "I think this commission should know Morton Thiokol was so concerned that we recommended not launching below 53 degrees Fahrenheit and that was sent to NASA in writing."

—

'You better be careful' • Boisjoly also testified before the commission and was the anonymous source for news stories. He and others from Morton Thiokol suffered psychologically; he was blamed by some at the company for helping to expose its role in the disaster.

"It was hard, very hard," said Boisjoly's daughter, Darlene Richens of Nephi. Dead animals showed up in their mailbox; someone tried to break into their home.

"Dad got a threat on his phone," she said. "They said, 'We know you walk in the mornings. You better be careful next time you go walking.' "

Boisjoly suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and took a leave of absence from the company before he departed permanently. He unsuccessfully sued the company.

Another engineer, R.V. Ebling, also told reporters he considered himself one of casualties from the Challenger and said he had been under the care of a psychiatrist.

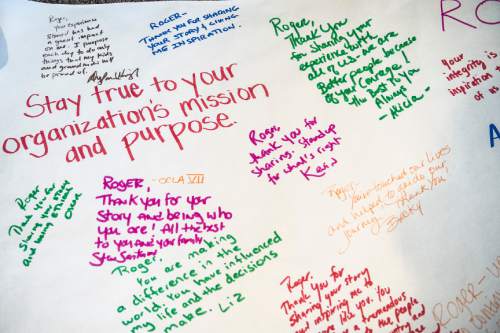

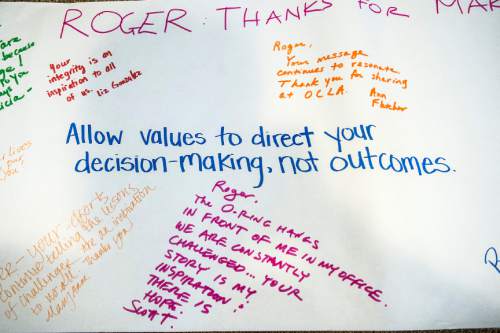

Boisjoly recovered and began to speak about the engineering and leadership failures that led to the disaster.

"He turned it very much into a positive," said Richens. "He went and spoke all the time."

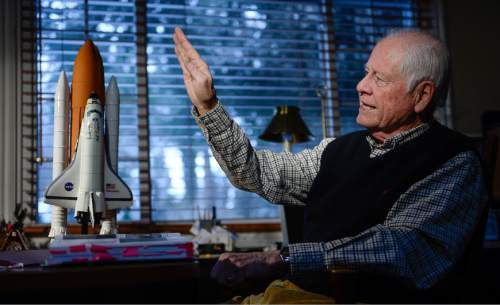

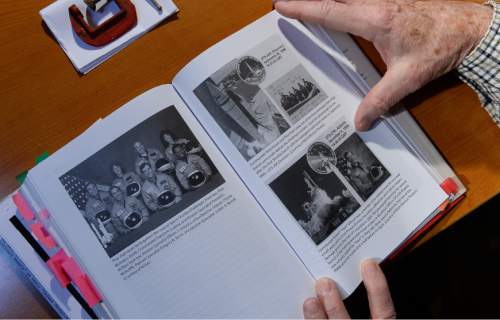

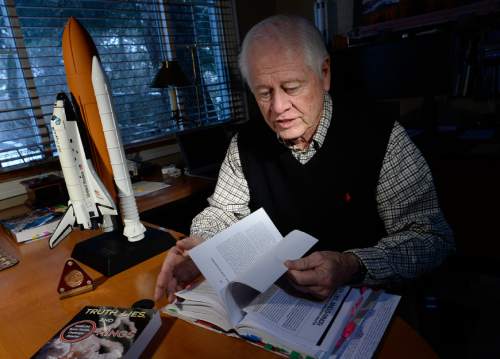

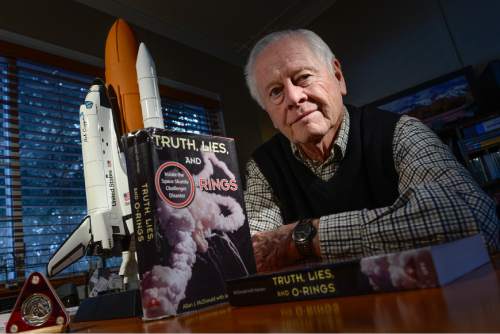

McDonald collected his records on the incident and wrote a book titled "Truth, Lies, and O-Rings: Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster."

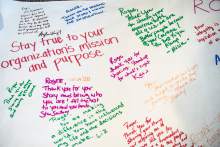

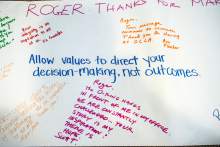

Now he gives lectures to Navy pilots, engineering students and others about what went wrong, in what has become a classic case study in engineering ethics and leadership practices.

—

Last launch • Morton Thiokol paid millions of dollars to settle claims over its role in the Challenger disaster and has gone through several changes in ownership and names. It now employs about 2,100 people in the Brigham City area, Knudson said. Lund, the Morton Thiokol vice president who had eventually agreed to the launch under pressure, declined to talk about the anniversary of the explosion.

The space shuttle program was grounded for more than two years while the boosters were redesigned and personnel changed at Morton Thiokol and NASA. Still, in 2003, the space shuttle Columbia broke up on re-entry. Although a piece of foam insulation had broken off and damaged the craft during launch, NASA officials decided it would be safe. The seven people aboard died.

"I called that lessons learned from Challenger but forgotten," said McDonald.

Salt Lake City attorney Danny Quintana, who once represented a Utah engineer in a lawsuit over the Challenger disaster, has written a new book in which he proposes new spending on space exploration as a productive alternative to military spending.

"The damage that was done to the nation's space program by the Challenger disaster … scared America away from really actively pushing hard," he said. "That was too bad. I think we should already have colonies on Mars."

The last space shuttle launch was July 8, 2011.