This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

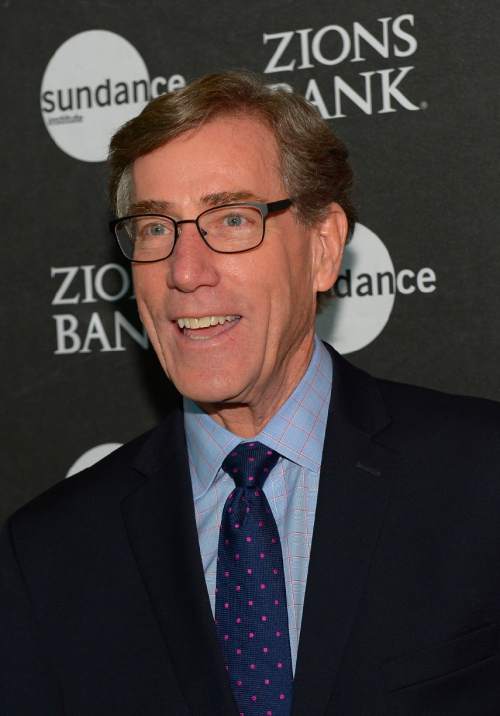

Ask heavyweights in Utah's political community about Zions Bank President and CEO Scott Anderson and they'll say he's "Utah's unelected governor," a "backroom boss" and the man you must see before running for office.

Anderson dismisses these descriptions, with nervous laughter, as "a bunch of poppycock."

He would rather talk about the role others play in public policy.

This is quintessential Anderson, according to those who know him best. He deflects attention whenever possible, speaks clearly yet humbly and wields his considerable influence with a light touch.

"It is almost like the man doesn't have an ego. I think that gives him a lot of credibility," said Frank Pignanelli, a prominent lobbyist who isn't among the 10 lobbyists registered to represent Zions Bank.

Anderson may not want to hear it, but in Utah's business community, he has played a singularly important role in civic affairs, stretching far beyond sitting on a board of directors or cutting a big check for a charity.

He has come out in support of immigration reform, tax increases to fund transportation projects and a revamping of the state's election system to reduce the power of caucuses — all issues that had plenty of opposition.

He's a Republican, but he's also raised money for and endorsed Democrats, including former Rep. Jim Matheson.

He has stuck his nose into tight elections and has occasionally found himself backing the vanquished, as he did in Salt Lake City's 2015 mayoral race when he supported former Mayor Ralph Becker over the newly elected Jackie Biskupski. Anderson said he would let Biskupski know that: "I would work with her and I would do everything I could to make her administration successful."

And, for a time, he invited prominent Republicans to visit his second floor office across from LDS Temple Square in downtown Salt Lake City in hopes of persuading them to run against Sen. Mike Lee, only to eventually make nice and endorse the first-term Utah GOP senator.

So why is Zions Bancorporation, with operations in 11 Western states, taking a stance on Utah's electoral system or the mayor's race? It's not, and that is something Anderson regularly has to explain.

"I do have to be careful and I try to be very careful in making clear when I speak for the bank and when I speak as an individual citizen," he said. As an example, he signed as "a downtown business leader" an opinion column in The Salt Lake Tribune supporting Becker.

Unlike other civically engaged business leaders, such as Gail Miller, who runs the Larry H. Miller empire, or industrialist/philanthropist Jon Huntsman Sr., Anderson answers to a boss. Harris Simmons runs the broader Zions Bancorporation that operates Zions in Utah and Idaho, along with banks under different names in nine other states.

Simmons' philosophy is that a bank functions better when its employees are actively involved in the community. He calls it creating "value" and sees it no differently than creating value for stockholders. Practicing what he preaches, Simmons serves on the Utah Board of Regents, which oversees' the state's public colleges. Another member on the 16-person board is his cousin and Anderson's wife, Jesselie Anderson.

Simmons hasn't been out front on nearly as many issues as the man who oversees his Utah operation, and he occasionally disagrees with a public position Anderson has staked out. Still, Simmons doesn't require Anderson to fill him in before endorsing a candidate or nudging a politician on an issue he cares about.

"I cut him as much slack as I possibly can because, at the end of the day, I think his heart is in the right place," Simmons said. "He has a lot to offer and it is part of who he is."

Anderson said he has pulled back on occasion when he thought a political issue would be too hot for the bank to handle and noted he often seeks Simmons' guidance.

"I counsel with him a lot and he gives me really good advice on issues," Anderson said. "He is the chair, he is my boss and I follow instructions."

—

Family ties • Anderson's father, Aldon, was an elected district attorney and a federal judge in Utah, who encouraged his children to follow current events and get involved. When attending the University of Utah, Anderson wrote for The Daily Utah Chronicle and ran for student body president. He lost that first and only run for public office.

He met his wife, Jesselie, when she was working as a congressional staffer in Washington, D.C. Her father, Haven Barlow, served a record 42 years in the Utah Legislature, including six years as the Senate president. Anderson said he's trying to follow the example set by his family and the late Roy Simmons, who recruited him to Zions Bank from Bank of America in 1990.

"I do think as a member of a democracy that we have an obligation to make it work," he said, "and you make it work by being involved>

He has encouraged his employees to follow his lead. Zions Bank sends regular reminders to its nearly 6,000 Utah employees about registering to vote, attending political caucuses and participating in elections. In 2014, 822 Zions Bank employees attended the Republican or Democratic caucuses and 234 were elected delegates. About 380 spouses of Zions employees were also elected as either state or county delegates.

How does Anderson know this?

"We track it," he said. "It is just a way of measuring our involvement in the community."

Beyond that, four bank employees currently serve in the state Legislature — Sens. Luz Escamilla, D-Salt Lake City, and Kevin Van Tassell, R-Vernal, and Reps. Robert Spendlove, R-Sandy, and Jacob Anderegg, R-Lehi.

Two of the past five House speakers have been Zions Bank employees, with the most recent being David Clark, who left the Legislature in 2012. Clark retired from Zions Bank in January, ending his 40-year banking career, the vast majority of which was spent overseeing operations in southern Utah.

Every two years, Clark would send a formal request to Anderson asking for permission to run for re-election and in return he would receive a letter telling him to represent his constituents and not the bank. Anderson sent similar letters to every employee who sought elective office.

But when it was clear Clark was poised to become speaker in 2008, Anderson took it a step further. He offered Clark a new job in charge of special projects. He reported directly to Anderson, and had the flexibility to work any hours he needed so his job never conflicted with his public service. He insists his boss never pressed him on any legislation.

Clark took a leave of absence to run for Congress in 2012. After failing to get the GOP nomination, he returned to the bank.

"Scott is high level and big picture about his influence," Clark said. "I have never had anyone from Zions Bank tell me how I need to vote."

—

Future candidate • With his obvious interest in politics and deep involvement, Anderson has been floated as a potential candidate for governor or senator, though he insists he has never seriously considered it.

"My wife would be a terrific candidate. She should run," he said, only half joking.

Jesselie Anderson is a leader in the Education First campaign, pushing to place an income-tax increase to support public education before voters. She said her husband has become more politically engaged during the past decade, but that she never would let him run for office.

Her hesitation is not about a rough-and-tumble campaign or a steep drop in pay. She believes he's better positioned where he is to make a difference on issues he cares about.

"Sometimes there are people who can almost have more influence from not running for office," she said.

Pignanelli, a Democrat, said if Anderson did run for statewide office, he would be formidable.

"If he announced he was going to run for governor, it would put the Democrats in a hard place," he said. "They might as well nominate him, too."

That's because Anderson is clearly a moderate prone to supporting well-positioned politicians willing to embrace compromise. He had that in mind when he endorsed Matheson over Mia Love in 2012, a move that Matheson said gave his campaign a boost and that Love's people said felt like a body blow.

"He represented the state well. His views were similar to mine," Anderson said. "I think to have one member of our delegation in the party of the administration makes sense because Utah has a lot of federal land."

Since Love has taken over that congressional seat, after Matheson declined to run again in 2014, Anderson has backed her, noting she sits on the House committee that oversees financial services. He said he appreciates her thinking on how financial policy would impact a small business trying to get a loan. He also has given Love a $2,700 contribution.

Anderson has personally given federal candidates and political entities $167,700 through the years, with his biggest single contribution a $32,400 check he wrote to the National Republican Senatorial Committee in April 2014, when Utah had no Senate race. He also gave $1,000 to the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee that same year. He's been active in state races as well, giving roughly $30,000 to Republican Gov. Gary Herbert for his past two elections.

—

Pivoting on Lee • Anderson's political flexibility was on full display last year, when he funded a series of polls in an attempt to find a Republican to challenge Lee, who famously championed the strategy to fight the Affordable Care Act that led to a 16-day government shutdown in 2013. Anderson believes that shutdown hurt Utah and its business community.

Dan Jones, Anderson's preferred pollster, created head-to-head comparisons between Lee and several prominent Republicans, such as former Govs. Mike Leavitt and Jon Huntsman Jr., Rep. Jason Chaffetz, former Hinckley Institute Director Kirk Jowers and Josh Romney, the son of former GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney. He then met with each man in turn, presenting the poll results and encouraging him to run. If more than one said yes, he'd back the person with the best approval rating.

No one said yes.

This gambit became public, embarrassingly, when Anderson's close friend, Jon Huntsman Sr., who also opposed Lee, talked about it to Politico, a D.C. publication.

With no candidate to champion, Anderson decided to abandon the effort to replace Lee and, along with Huntsman Jr., led the senator's re-election campaign.

Lee said he has a fine relationship with Anderson. For his part, the bank president said he didn't directly recruit anyone to run against the senator, though he acknowledged his frustrations, the polling he commissioned and that Dan Jones shared the results with key political figures.

Anderson said he came to support Lee because he believed the incumbent had become more open to finding common ground with Democrats, pointing to Lee's ongoing work on a bill to reform the criminal-justice system as an example.

"He has made changes," Anderson said. "Not that he has become liberal, he has stayed true to his values — but he is accomplishing some really significant things in Washington by being able to reach across the aisle and negotiate some really good pieces of legislation."

This wasn't the first time Anderson's political support has put him in a bit of an awkward spot. In 2011, he agreed to be a key leader of H PAC, a political entity created by Utahns to support an eventual presidential campaign of Huntsman Jr.

The thinking was Huntsman, then President Barack Obama's ambassador to China, would ramp up with an eye on the 2016 campaign. But then a team of political operatives nudged him toward running in 2012 — against Mitt Romney, a fellow Mormon, who is beloved in Utah.

Huntsman asked for Anderson's backing and he stayed loyal, though he knew it would cause him some grief.

"Utah is a small society and we have a lot of friends," he said, "and sometimes it is tense when you support one over the other."

When Huntsman's campaign ended after the New Hampshire primary, Anderson quickly became a Romney donor and supporter.

Pignanelli believes Anderson has been able to take stances without harming his relationships or the bank's because "people don't assign any personal motive or agenda."

"I have heard people say they disagree with Scott Anderson, but I haven't heard anyone say they don't like him."

—

Clones? • Anderson continues to serve as a key adviser to Herbert, who is fond of saying he believes there must be Anderson clones, because he is seemingly at every public event and in the thick of so many issues.

Anderson is also a primary backer of Utah Policy, a website offering political news and polling that is owned by LaVarr Webb, a Leavitt protégé who once registered as a lobbyist for Zions Bank. He has helped bankroll the Women's Leadership Institute, run by former state Sen. Pat Jones, whose husband is pollster Dan Jones, and the Olene Walker Institute of Politics and Public Service at Weber State University.

Lane Beattie at the Salt Lake Chamber credits Anderson with the idea for the World Trade Center of Utah and for USTAR, a state effort to boost the technological expertise at the U. and Utah State University.

Becker, the former Salt Lake City mayor, says it was Anderson who encouraged him to create a revitalization plan for Regent Street, just east of Main Street. Construction is now underway on a pedestrian-friendly upscale entertainment district linked to the new George S. and Dolores Doré Eccles Theater, set to debut this fall.

So what issues has Anderson been thinking about lately? Like his wife, he believes Utah needs to find a way to funnel more money into education. He's also concerned about water, suggesting that maybe it is time to raise the dike around Willard Bay or put in the Lake Powell pipeline — an expensive and controversial project.

"Or do we not do any of that and just slow our growth," he said, "because as the population increases you are going to have to have more water."

Anderson recognizes that part of his clout comes from Zions Bank, which has ties directly to Brigham Young and the Mormon hierarchy. But part of it is his personality and ethos. He sees himself as a community caretaker, a role that has been played through the years by the likes of the late Jack Gallivan, former publisher of The Tribune; Spencer Eccles, former First Security Corp, CEO and chairman; and Huntsman Sr.

But this mover and shaker, who is clearly uncomfortable with too much attention, won't likely have his name on a prominent building anytime soon.

mcanham@sltrib.com Twitter: @mattcanham