This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Browsing a favorite used-book store in Provo in 2004, Richard Isakson came across "One of Ours," an unfamiliar novel by a familiar author.

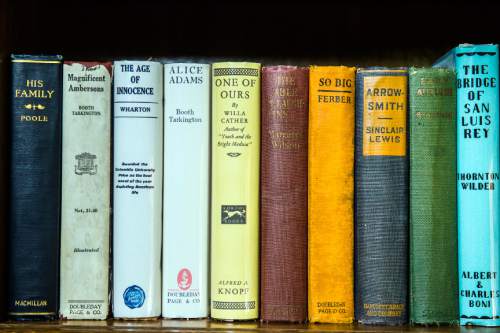

With a World War I soldier in a doughboy helmet on the cover, the book seemed a far cry from Willa Cather's Midwestern-set works like "O Pioneers!" Isakson, then a psychology professor at Brigham Young University, bought it — and loved it.

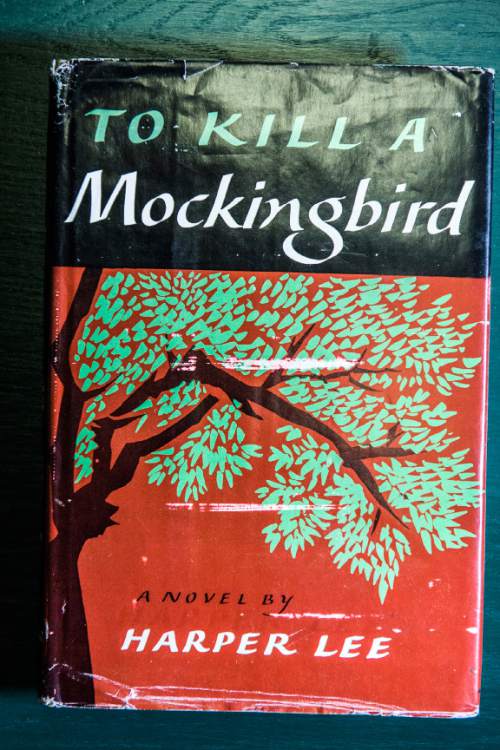

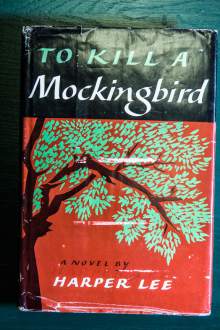

He noted it was heralded as "Winner of the Pulitzer Prize" and, always hungry for more good books, checked the full list of winners. He found he had read some of them — "To Kill a Mockingbird," "The Age of Innocence," "Lonesome Dove" — but there were many more he'd never heard of.

So, "thinking that if they'd won that prize — which I consider to be the most prestigious award for fiction writers in the U.S. — that would be a book worth reading," he printed a list and started searching and reading.

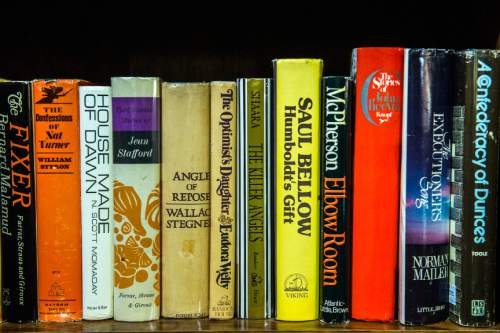

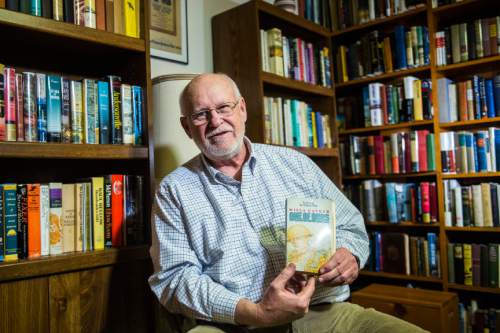

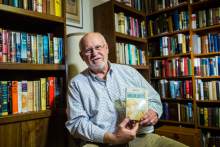

Now, 12 years and 86 books later, Isakson is finishing his last Pulitzer-winning novel, Norman Mailer's "The Executioner's Song."

The Pulitzer goal "shifted my reading focus," he says. "It's challenged me to read books that I might not've been drawn to, helped me discover books I had never known of."

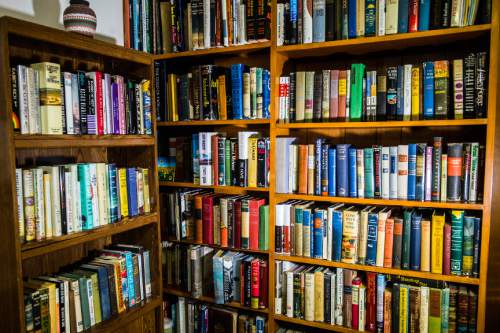

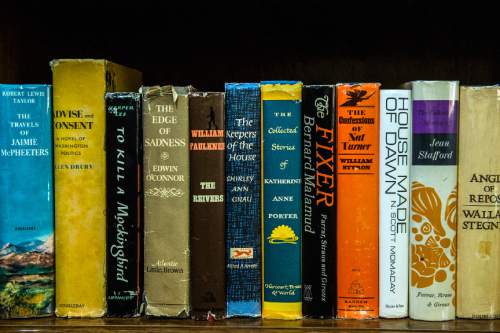

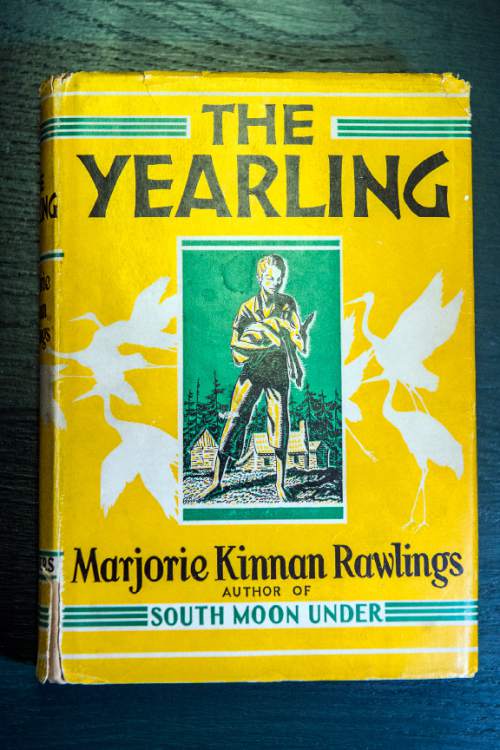

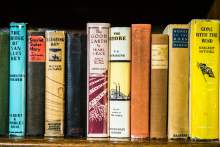

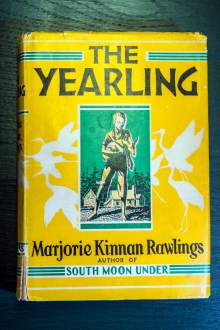

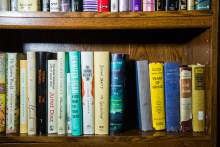

Isakson rattles off a dozen titles when he tries to name a favorite Pulitzer. "One of Ours" is certainly up there. The unassuming paperback that started it all, its pages having come unglued from the binding after much reading, now sits in pride of place atop a bookcase in Isakson's Provo home. It's one of two bookcases that house Isakson's collection of every Pulitzer fiction winner from 1918 to 2015, many of them beautiful first editions.

Reading an antique book — with its thick paper, musty smell and inscriptions written by earlier owners — pulls him deeper into the story and the world it was written in, he says.

"Some people collect antiques, and they buy this little intricate glass thing and maybe they'll put it on a shelf but nobody touches it," Isakson says. "No one's serving cookies on it. But with these books, I haven't hesitated to read any of them, even the rare ones."

His collection complete but for a space he's left for the 2016 winner, which will be announced April 18 at 1 p.m. MT, all Isakson has to do now is wait.

—

'Whole[some] atmosphere' • In his 1904 will establishing his namesake prizes, Joseph Pulitzer said an award should be given to the novel that best presented the "whole atmosphere of American life, and the higher standard of American manners and manhood."

But when Nicholas Butler — president of Columbia University, which administers the prize — presented the plan for the Pulitzers in 1915, he added a syllable, specifying the American atmosphere portrayed be "wholesome."

Jurors felt hamstrung by that requirement, according to Pulitzer historian John Hohenberg. In 1920, English professor Stuart Sherman wrote to the group's chairman, "We ought not to crown a licentious work, but I don't believe we should hold off till a novel appears fit for a Sunday School library."

No prize was awarded that year, an occurrence that would be repeated 11 times during the history of the category.

The moral parameter also rankled authors, perhaps none more than Sinclair Lewis, whose novels satirizing the hypocrisies of small towns and middle-class Americans found favor with Pulitzer jurors but lacked wholesomeness. In 1921, the Pulitzer advisory board overruled the three-member jury that had recommended Lewis' "Main Street" and gave the prize to "The Age of Innocence" by Edith Wharton.

In 1922, jurors knew they'd have another uphill battle with Lewis' best-selling "Babbitt" and instead recommended, "without enthusiasm," the prize be given to "One of Ours."

Lewis' "Arrowsmith," with its more uplifting message, was awarded the Pulitzer in 1926. But he rejected the prize, declaring in a scathing letter that the award's terms dictated that "appraisal of the novels shall be made not according to their actual literary merit but in obedience to whatever code of Good Form may chance to be popular at the moment" and urging other novelists to decline the prize.

The next year, "without comment or explanation," the second syllable of "wholesome" was dropped from the requirements.

But controversy over morals still dogged the prize; in 1941, Butler found "For Whom the Bell Tolls" offensive and persuaded the board to not give any award rather than give one to Ernest Hemingway.

—

Diving in • Hemingway did eventually receive the Pulitzer, in 1953 for "The Old Man and the Sea." Much as the Oscar sometimes seems to be awarded in recognition of an actor's body of work, the Pulitzer could represent the cumulative merit of an author's works or serve as a "make-up," Isakson says, for an earlier, better novel that was overlooked.

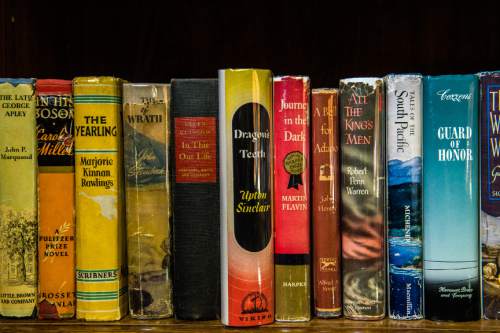

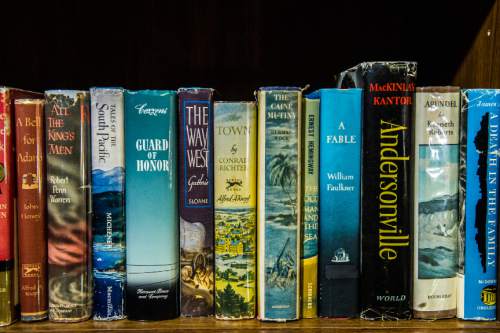

William Faulkner won twice, for "A Fable" and for "The Reivers," which carry less name recognition than his "As I Lay Dying" or "The Sound and the Fury." Upton Sinclair, most famous for "The Jungle" and "Oil!" — the loose basis of the film "There Will Be Blood" — won for "Dragons Teeth," the third book in an 11-volume series, today available only used or via an ebook distributor that specializes in repackaging lost or out-of-copyright books.

Though one would think winning the Pulitzer guarantees your book will live forever, many of the winners from the 1920s and '30s are long out of print and out of the consciousness of the literature community. Tracking them down was a feat, but it wasn't a chore for Isakson and his wife, Marné, a longtime English teacher and perhaps an even more avid reader.

Armed with his list of winners and authors, they scoured bookstores across the state and country, from tiny towns in Colorado to San Francisco and Atlanta. Searching a used-book shop is a thrill Isakson likens to fishing — you're always hoping the book you've been seeking is languishing in these stacks.

He read the winners in the order he could find them, so his quest was never hampered by an elusive title. He expanded his search to include better copies of Pulitzers he already owned, as well as other books by the winning authors.

"The real fun was finding a good edition that the bookstore didn't appreciate" and paying under $10 for a book likely worth hundreds, Isakson says.

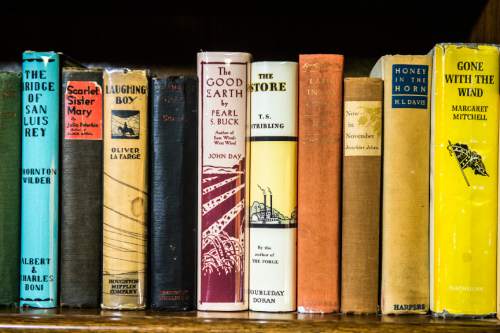

The older, hard-to-find Pulitzer winners often came with the biggest payoff, and not just when it came to bargains. The 1929 winner, "Scarlet Sister Mary" by Julia Peterkin, has been "absolutely forgotten, nobody seems to have read it," Isakson says, but they both fell in love with the story of Mary, a black woman struggling with love, sin and limited choices in the post-slavery era, and have bought extra copies to pass along to others.

"It's just beautifully written. The first paragraph just blew me away," says Marné.

Lyrical writing is a must for her; she often reads aloud during long car trips. "It can't just be a good story — I have to savor the language," she says, citing "The Grapes of Wrath," "To Kill a Mockingbird" and "Beloved" as some of her favorite Pulitzers.

Richard Isakson's priority is story; he loves Tony Hillerman and John Grisham thrillers, as well as Harry Potter . "I like to be entertained, I admit it," he says.

Characters bring history to life, "which I unashamedly like about fiction," he says. "Someone could write a nonfiction book about the cattle drives in Texas," he notes, but it wouldn't be as captivating as the story of Gus and Captain Call in "Lonesome Dove."

And though the titles and plot descriptions of some of the lesser-known winners didn't immediately captivate him, he says, once he began reading he usually was swept away.

Tell the Tribune: What's your favorite Pulitzer-winning novel?

—

Never not reading • Isakson maintains two huge binders with background information on the Pulitzer winners and their authors, as well as his reactions to the books — which he sometimes shares on his ReadPulitzerFiction.blogspot.com.

He read about three or four winners a year, plus related titles; not wanting to go into a novel without context, Isakson would read an entire series if one if its titles had won the prize.

There were a few he didn't love, but "I've just decided I would read all of them, no matter what," he says, "so I've never put one down and not finished it."

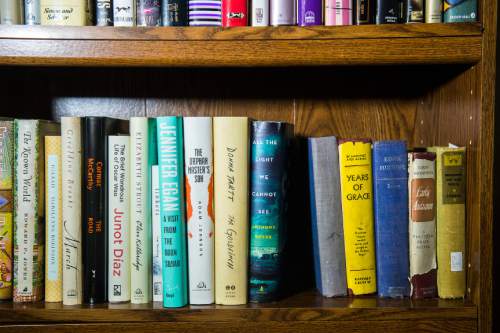

Faulkner's "A Fable," with its page-spanning sentences, was "tough sledding," though the same author's "The Reivers," which won a decade later, was "delightful." Isakson appreciated 2007's "The Road" in theory but can't say he truly enjoyed reading Cormac McCarthy's dark, apocalyptic tale. And he skimmed through parts of the offbeat 2011 winner "A Visit From the Goon Squad."

It was a letdown when no novel earned 2012's award, though he says it speaks to the quality of the prize that there's no obligation to crown a winner every year. Subsequent winners "The Goldfinch" and "All the Light We Cannot See" made up for the disappointments of 2011-12; both had the kind of gripping plot and evocative language that win accolades in the Isakson home.

But don't worry about Isakson if there's no Pulitzer fiction prize given next month. He's casually started collecting winners of the National Book Award.

Twitter: @racheltachel —

Pick Your Pulitzer

Tell the Tribune: What's your favorite winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction?

This package is part of coverage supported by a grant to The Salt Lake Tribune by the Pulitzer Prizes Centennial Campfires Initiative, a joint venture of the Pulitzer Prizes Board and the Federation of State Humanities Councils in celebration of the 2016 centennial of the Prizes. This year-long project in Utah is a collaboration between The Salt Lake Tribune, Utah Humanities, Utah Public Radio and KCPW. Diverse voices?

Fifty-five men and 30 women have been awarded the prize, the majority from the East Coast or the South. Though many of the winning novels are set outside the U.S., all of the authors have been American, to comply with Joseph Pulitzer's original parameters.

The prize still "celebrates distinctly American voices," notes Siân Griffiths, director of creative writing at Weber State University, "and hopefully is getting more inclusive of the diversity those voices. I think it's getting on people's radar that we need to be looking at diverse voices."

She points to Toni Morrison's 1988 win as an important moment in the Pulitzer Prizes. " 'Beloved' was super innovative — that one takes on the history of race in America in a way that few books ever have."

Junot Díaz's "The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao," which won 20 years later, also "makes a lot of innovative moves," Griffiths says, "and breaks down some racial stereotypes. He produced some wonderful characters that readers can connect with."

Griffiths doesn't have a prediction for the 2016 prize, but she says Louise Erdrich, a finalist in 2009, is "an oversight" and hopes the Ojibwe author of more than 20 works will eventually win the main prize.

"It's a good thing that [the Pulitzer] has evolved over time. We're constantly in a state of evolution and it's good that the prize moves with that," she says.

What kind of writing wins Pulitzers?

"If a writer wins the Pulitzer, it's going to bring new readers to their work, and any writer is hoping to find an audience for their work," says Siân Griffiths, director of creative writing at Weber State University. "On the other hand, there are a lot of writers who are interested in more avant garde work, breaking down some of the old ideas of how a novel should be constructed, for whom the Pulitzer is less impactful."

Those experimental books tend to find more favor in the National Book Critics Circle Award and the PEN Awards, whereas "Pulitzer-winning books tend to be books that will connect to a fairly large audience," she says.

Anthony Doerr's "All the Light We Cannot See," which won the 2015 Pulitzer, was hugely successful even before it won the prize — something that was a bit surprising, Griffiths says, as "Doerr's previous work had really flown under the radar. He focused on creating beautiful sentences, which doesn't necessarily translate to popular success."

But Doerr apparently hit upon the magic formula with "All the Light We Cannot See," which, Griffiths says, had the "plot and strong characters that did connect to people, and retained beautiful sentences." Lesser-known Pulitzer fiction winners Richard Isakson recommends

"One of Ours" by Willa Cather

"So Big" by Edna Ferber

"Scarlet Sister Mary" by Julia Peterkin

"Laughing Boy" by Oliver La Farge

"The Store" by Thomas Sigismund Stribling

"A Bell for Adano" by John Hersey

"The Keepers of the House" by Shirley Ann Grau

"Dragons Teeth" by Upton Sinclair

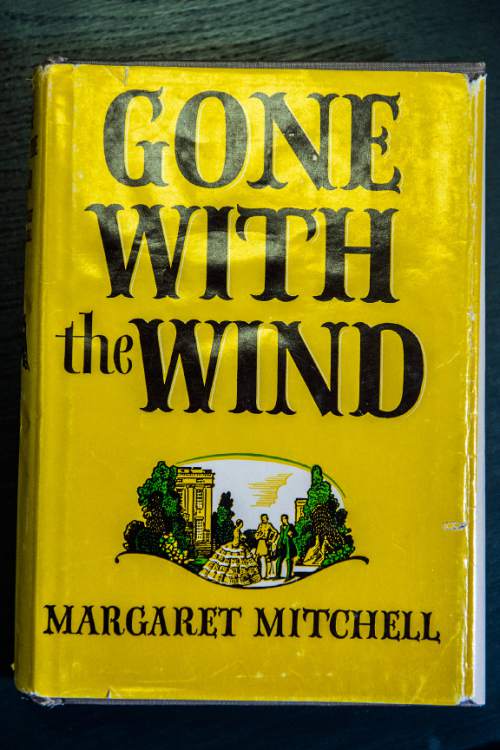

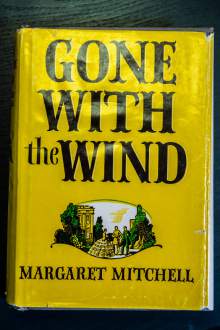

"Gone With the Wind" by Margaret Mitchell (not lesser-known given the movie version, but Isakson stresses that the book is "a different experience" and a captivating look at the South during and after the Civil War) —

Diverse voices?

Fifty-five men and 30 women have been awarded the prize, the majority from the East Coast or the South. Though many of the winning novels are set outside the U.S., all of the authors have been American, to comply with Joseph Pulitzer's original parameters.

The prize still "celebrates distinctly American voices," notes Siân Griffiths, director of creative writing at Weber State University, "and hopefully is getting more inclusive of the diversity those voices. I think it's getting on people's radar that we need to be looking at diverse voices."

She points to Toni Morrison's 1988 win as an important moment in the Pulitzer Prizes. " 'Beloved' was super innovative — that one takes on the history of race in America in a way that few books ever have."

Junot Díaz's "The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao," which won 20 years later, also "makes a lot of innovative moves," Griffiths says, "and breaks down some racial stereotypes. He produced some wonderful characters that readers can connect with."

Griffiths doesn't have a prediction for the 2016 prize, but she says Louise Erdrich, a finalist in 2009, is "an oversight" and hopes the Ojibwe author of more than 20 works will eventually win the main prize.

"It's a good thing that [the Pulitzer] has evolved over time. We're constantly in a state of evolution and it's good that the prize moves with that," she says.