This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The modern push to ordain women to Mormonism's all-male priesthood was publicly announced March 17, 2013 — the 171st anniversary, not coincidentally, of the faith's female Relief Society.

That 19th-century event in Nauvoo, Ill., was then — and remains today — a defining moment for women in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The 20 women who gathered that day in 1842 above a dry-goods store in the burgeoning "City of Joseph" believed they had a loftier purpose than mere benevolence: Mormon founder Joseph Smith promised they would become "a kingdom of priests," partners with men in creating a "holy society."

Eliza R. Snow — poet, leader, suffragette — drafted a constitution for the newly named Nauvoo Female Relief Society, then became its secretary and dutifully kept the minutes. Her record became a Magna Carta for Mormon women, noted and quoted through the ages.

The organization met 33 times in Nauvoo, during which the Mormon prophet delivered six sermons specifically to women.

Smith encouraged them to use their "gifts of the spirit," including speaking in tongues, prophesying, receiving visions, and healing.

"Respecting the female laying on hands," the minutes report, the Mormon prophet "further remark'd, there could be no devil in it if God gave his sanction by healing."

Though Smith had secretly introduced plural marriage to a handful of families, in their meetings the women chastised those who would spread what they believed were false rumors of adultery and inappropriate relations.

The LDS leader's wife, Emma Smith, the first Relief Society president, "rose and said all idle rumor and idle talk must be laid aside yet sin must not be covered, especially those sins which are against the law of God ... said she wanted none in this society who had violated the laws of virtue."

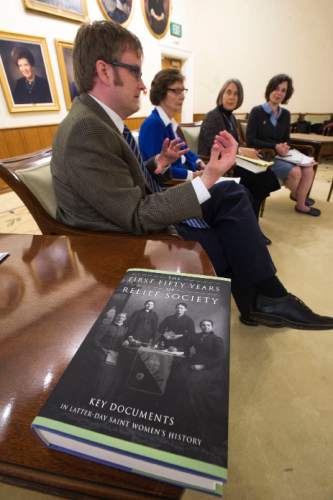

Now the LDS Church Historian's Press has published those minutes, Smith's sermons and other original documents in a landmark volume, "The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women's History."

The hefty 800-page tome — edited by Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook and Matthew J. Grow — includes 78 documents chosen from thousands of available records, complete with analysis and annotations. It also includes 400 biographical sketches of men and women mentioned in the documents.

—

Little-known facts • The book details aspects and episodes of Relief Society history that many Mormons may not know. For instance:

• Potential Relief Society members had to be vetted by the group before they were allowed to join. By the end of 1844, members numbered more than 1,000.

• The terms "ordain" and "set apart" were used somewhat interchangeably.

• On two occasions in the 1840s, the editors write, Relief Society members publicly denounced "every form of licentiousness," including polygamy. The latter statement, titled "The Voice of Innocence from Nauvoo," was read aloud by Emma Smith and unanimously approved.

• Joseph Smith seemed to blame "Voice of Innocence" for the "mounting fury he faced from dissidents" — tensions that eventually led to his 1844 murder.

• His immediate successor, Brigham Young, also believed that Emma Smith's opposition to plural marriage helped fuel anti-Mormon attacks. So Young disbanded the society. It didn't reconvene until the mid-1850s in Utah and mostly as a local initiative. In later decades, the organization proved a crucial aid in the silk industry and other economic undertakings.

• Snow, who later became Relief Society president, and other Mormon women leaders harnessed the group's energy to push for suffrage.

The new book is "the most important work to emerge from the Mormon press in the last 50 years," writes Pulitzer Prize-winning Harvard historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, " ... a signal contribution to religious studies, women's history, and the economic and social history of the American West."

Historians have "rarely, if ever, had such a thorough view into the women's side of a new religious movement that became a world religion," says Ann Braude, director of the Women's Studies in Religion Program at Harvard Divinity School. "The opportunity to view from inception the intended meanings of women's distinctive practices in the words of both the authoritative male founder figure and the women themselves makes this a gold mine for historians."

Today, Mormon feminists still debate the question of an all-male priesthood, the fallout from the faith's long-abandoned practice of polygamy and the urge to regain permission for women to perform healing rituals.

Do these documents settle all those issues? No.

They do show that, back then, Relief Society members debated whether women should be involved in charitable work that had been a male bishop's job, whether women should speak in tongues and heal, when women should "exhort" the church, and how the partnership between male and female leaders should work.

In the 1850s, some male Mormon authorities changed the public account of Smith's words to the women from "I now turn the key to you in the name of God" to "I now turn the key in your behalf."

These documents clearly show that LDS female forebears commenced the conversation about "women's authority and women's responsibilities," Derr says. "That conversation is ongoing."

—

Setting precedents • In the early 2000s, Derr, at work on a biography of Snow, joined forces with Madsen, studying the life of a later Relief Society president, Emmeline B. Wells. The two scholars determined the documents should be published, but with appropriate context. When they won the go-ahead from LDS officials, they enlisted the help of Grow, a former assistant to Derr and now a researcher in the church's history department, and later Holbrook, who was hired to replace Derr after the senior historian retired. Dozens of others helped collect, sort, annotate and fact-check thousands of items.

The final product provides institutional perspective, largely supportive of church teachings. There are no critical voices in the book, but anguish and pain emerge as these early Mormon women work through their feelings and how they are perceived by others.

"They were stereotyped as stupid and degraded, quarrelsome and ugly," Derr says. "They had to ask themselves: Who are we? We are daughters of God. We are a holy nation. We have divine duties."

The book is divided into four time periods: Nauvoo from 1842 to 1845; an ad-hoc approach in Utah from 1854 to 1866; a churchwide program from 1867 to 1879; and battling with the federal government over plural marriage and working for women's suffrage from 1880 to 1892.

As a researcher, Ulrich says "having actual references for long-known historical changes — such as Young's ban on Relief Society meetings after Smith's death or the rewriting of Eliza's minutes in the 1850s — makes the patience, endurance and organizational savvy of the 'founding mothers' all the more remarkable."

Some readers may wonder how and why Mormon women "put up with such condescension" from male authorities, she says, but "almost as powerful" are hearing opposing perspectives noted in minutes — from one woman declaring herself "a woman's rights movement" and another "countering that she had always been happy with the rights of a woman."

Seeing those together, Ulrich says, "helps us to see the range of approaches."

—

Lasting impact • Do these minutes provide historical support for female ordination — as some modern feminists claim?

Focusing on whether Smith intended LDS women to be "ordained to the priesthood," Holbrook says, "shortchanges what was going on with the Relief Society."

The women "felt they had the power of God with them," she says, "and that they were doing God's work and building God's kingdom."

If they shared in the male priesthood, it was primarily in Mormon temples, where women still officiate in rites for women, while men administer the same rites for men.

In his phrase, "I now turn the key to you," Smith was addressing all the women, Madsen says, and referring more to "personal and spiritual empowerment than administrative."

So will such pioneering voices speak to contemporary Latter-day Saints, especially the faith's feminists?

Melissa Inouye, a Mormon scholar at New Zealand's University of Auckland, says "The First Fifty Years" takes topics that once seemed "edgy" and makes them "mainstream."

"The book candidly discusses Emma Smith's conflicted (and ultimately extremely negative) feelings about plural marriage," Inouye writes in an email. "It shows how Mormon women regularly laid hands upon the heads of the sick to heal, and how they blessed and anointed women at the beginning of labor — all with the approval and encouragement of the president of the church and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles."

Still, Inouye has mixed feelings about those early Mormons.

"I both do and do not want to be them." She would love, for example, to "wash and anoint my sisters in the early stages of labor" like her foremothers did, but she also "completely disagrees with the sisters who avowed that plural marriage is the crowning practice of the gospel of Jesus Christ."

Inouye is glad Mormons no longer live in a world "in which the president of the church (Brigham Young, of course) publicly addressed church bodies and said things like 'I don't want the advice or counsel of any woman' or 'There is no woman on the face of the Earth that can save herself — but if she ever comes into the Celestial Kingdom, she must be led in by some man.' "

On the whole, Inouye is pleased with the editors' humanizing of early church leaders — male and female.

"Mormonism's formal and informal institutions for women did not arise fully formed from a misty, rosy aura of universal accord but were hammered out in a back-and-forth process of knocks, patches and sore thumbs," Inouye writes. "This historical perspective assures us that the current and sometimes bruising negotiation over gender in the LDS Church is not a sign of degeneration and an approaching apocalypse, but par for the course."

Today's Mormons will get through their own debates, she says, "and ultimately be better for it."

pstack@sltrib.com Twitter: @religiongal Where the book can be found

"The First Fifty Years," which retails for $49.95, is available in bookstores and from online outlets. Digital selections can be read for free at churchhistorianspress.org

Editors to speak

• Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook and Matthew J. Grow will discuss their new book on Wednesday, March 9, at Benchmark Books, 3269 S. Main St., Ste. 250, Salt Lake City. The event runs 5:30-7:30 p.m. The editors will be speaking at 6 p.m. and will answer questions and sign books before and after that time. More information at http://www.benchmarkbooks.com .