This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

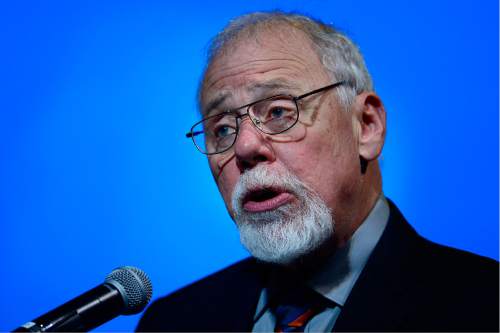

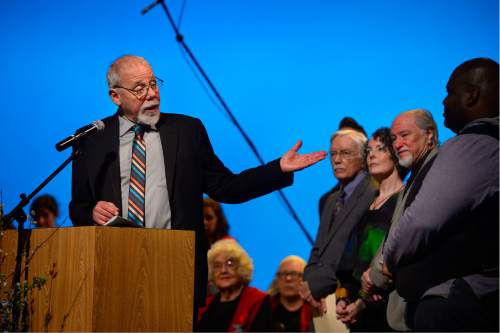

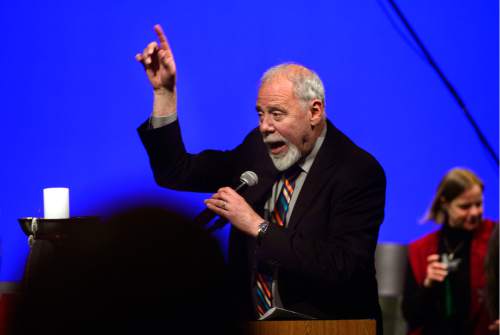

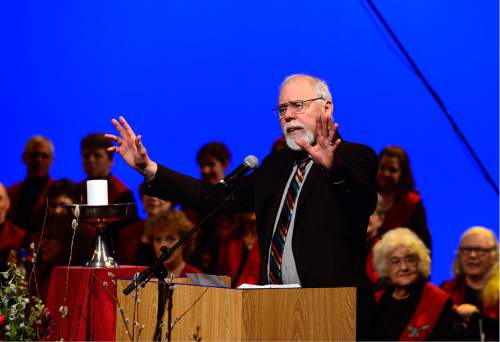

Boredom catapulted the Rev. Tom Goldsmith from the bastion of liberal Unitarianism in New England to the conservative backwaters of Utah.

It was 1987, and Goldsmith, a Harvard Divinity School graduate, was restless in historic Boston, hungry for social activism that would change lives.

Then came the offer from First Unitarian Church of Salt Lake City to serve as its minister. Goldsmith jumped at it.

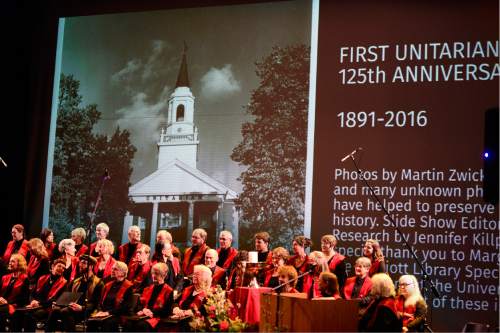

That same countercultural impulse and spirit of adventure 125 years ago prompted 127 charter members to break with Utah's predominant Mormon faith and set up the state's first Unitarian Society.

It began in the parlor of a family home, but later set up regular meetings at 138 S. 200 East in Salt Lake City in a space called "Unity Hall," where President William Howard Taft, a Unitarian, once attended a service. (The pastor at the time was an avowed socialist and humanist, though, so instead of embarrassing the Republican president, he suddenly discovered [wink-wink] he had a prior commitment.) By 1927, the congregation had moved to its current location in a traditional brick building at 569 S. 1300 East.

Throughout the decades, Unitarianism's big appeal has been that it did not require strict adherence to a set of beliefs about God or humanity. No dogma. No rituals. No food prohibitions. No intercessors with deity. For some, no deity — including Jesus — at all. Everything voluntary and individual. Do-it-yourself theology.

"We have always tried to teach that religion was not about memorizing creeds and doctrines, but about critical thought," Goldsmith says, "so a child can make hard religious or spiritual decisions rather than just following along with the tribe."

The congregation's first pastor, the Rev. David Utter, opened the door to biblical criticism — a radical approach at the time — and embraced God as an idea, not a person. Hundreds of like-minded believers joined. Professors, doctors, lawyers, environmentalists, teachers, activists and "come-outers" (former members of other faiths) all have found a home in the church.

The issues the congregation has tackled in its 125 years of existence may have evolved, Goldsmith says, but what has not changed is a progressive philosophy and a collective commitment to social justice.

Alan Coombs moved from Kansas in 1968 to teach history at the University of Utah. He found the Unitarians shortly after arriving and served as the congregation's president in 1986.

"My last official act was signing the first letter of contract for Tom Goldsmith," quips the retired professor.

In his decades at the church, Coombs has seen the ebb and flow of members and political causes.

The 1960s, when Hugh Gillilan was minister, were "turbulent years," Coombs recalls. The church — and everyone else in the country — were divided over U.S. involvement in Vietnam and whether to give sanctuary to draft protesters.

It was also a time for ecumenical actions.

First Unitarian joined with three other congregations (Congregation Kol Ami, the United Church of Christ and First Congregational) to build, with federal assistance, Friendship Manor, a senior-living tower at the southeast corner of 1300 East 500 South, Coombs says, "with significant reductions in rent for occupants of limited means." Representatives of the four congregations still sit on the manor's board.

Several other significant Utah organizations got their starts at the church — Salt Lake Acting Company staged its first plays there; Planned Parenthood of Utah held its organizing meeting there; a wide-ranging effort to provide furniture, clothing and other staples to African and Middle Eastern refugees; as well as an ongoing tutoring program were launched and promoted by members. In recent years, Tim DeChristopher, of oil-and-gas lease monkey-wrenching fame, made First Unitarian his spiritual home. He felt so embraced, welcomed and understood at the church, Coombs notes, that the climate activist is now studying at Harvard Divinity School — following in Goldsmith's path.

"In many ways, the church is more energetic now in pursuit of social-justice issues, especially environmental issues," Coombs says, "than any time in my experience."

Tim Chambless and his wife, Cathy Chambless, came to Utah in 1972. They've lived here since. He teaches political science at the U., and she is an analyst for Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.

When the couple began to have children in 1978, they wanted to find a church that shared their values. He grew up a fundamentalist Christian, she a Catholic, but they didn't want either faith for their offspring. They settled on First Unitarian.

"It's a place for people who don't fit into more traditional churches," Cathy Chambless says. "No one asks you if you believe in God or if you have been saved by Jesus."

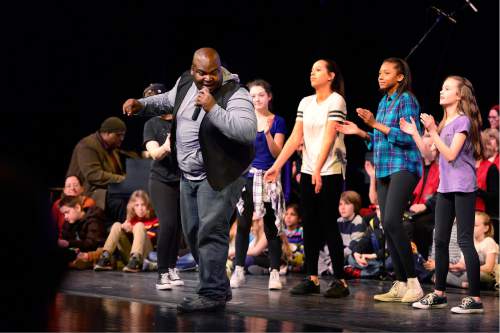

Chambless has seen the church's membership shrink and surge with the generations, but it now boasts a thriving youth population, she says. "The opening piece [at last month's 125th anniversary celebration] was a break dance by our junior and senior high kids. It showed the vibrancy of our community."

Her son and his wife recently had their baby daughter "dedicated" — a welcoming ritual — in the Unitarian community.

After more than a century, she says, there's still a need for these kinds of unconventional believers.

Twitter: @religiongal —

Big merger

The American Unitarian Association voted in 1961 to merge with the Universalist Church of America, which proclaimed universal salvation for all after death. The new denomination was called the Unitarian Universalist Association.

Later, Unitarianism expanded in Utah to include the South Valley Unitarian Universalist Society in Cottonwood Heights and congregations in Ogden and Park City.