This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Bob Ebeling had two careers: one sending people into space and the other sending them to nature. It was obvious which one was closer to his heart.

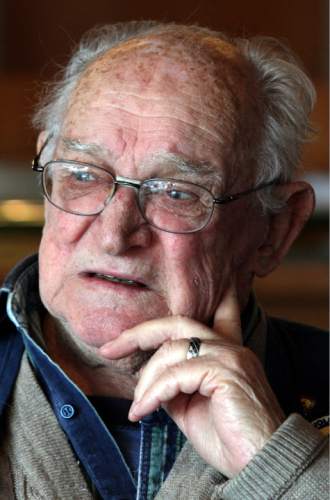

"I'd never trade one minute spent at the refuge for a million bucks," Ebeling said in 2013, while sitting at the volunteer desk in the education-visitor center at the refuge. "You appreciate what life has to offer, and Mother Nature is hard to beat. I've gained a lot of knowledge about what is important in life, and it isn't being a millionaire."

That life ended Monday, National Public Radio reported. The Brigham City man was 89.

Ebeling, a rocket scientist who tried to stop the Challenger shuttle launch, devoted himself in retirement to restoring one of the most important federal wildlife refuge systems in the United States: the 65,000-acre Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge.

Surrounded by arid deserts, the refuge is a critical oasis for waterbirds. More than 250 species of migrating birds use the marshy area to rest and eat every year — by the millions. When their much-needed rest stop's existence was threatened years ago, Ebeling helped save the day.

—

Nature lover • His passion for the birds started early. Growing up in Illinois, Ebeling used to lie in bed, listening to Canada geese fly over his house. Every fall, "they would come in like clockwork," Ebeling recalled in a 1990 Salt Lake Tribune interview. "They would fly in good weather and bad. You could hear those honkers all night."

Ebeling knew a thing or two about Mother Nature; some would say the Brigham City resident was on a first-name basis with her. After all, the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge was a major factor in his decision to move to Utah and work for Thiokol (now known as ATK) as a rocket scientist in 1962.

From that point on, Ebeling spent countless hours birding, hunting, hiking and boating at the beloved marsh. As an engineer, he worked on the fateful Challenger launch.

"The night before the launch, Ebeling and four other engineers at NASA contractor Morton Thiokol [the company's name at the time] had tried to stop the launch," NPR reported. "Their managers and NASA overruled them."

His daughter Leslie Ebeling Serna told NPR that the morning of the launch, Ebeling was distraught and drove to Thiokol's remote site.

"He said, 'The Challenger's going to blow up. Everyone's going to die,' " Serna recalled. "And he was beating his fist on the dashboard. He was frantic."

Ebeling later recalled praying and then breaking down crying in his office as the Challenger exploded.

On bad days, when the pressure of building rockets got the better of him, Ebeling found peace on the refuge.

"Space is the new frontier. It's the future of things. Ducks are in the past tense," he told The Tribune in 1990. "They are what we had and where we came from. Both have their place in society."

It's a good thing the birds had such a devout friend in Ebeling; they would need him.

—

A great flood • In 1983 and 1984, the Great Salt Lake flooded. The rising waters ravaged one of the oldest refuges in the federal system. Saltwater had invaded fresh. Dikes and water control structures were destroyed. Refuge headquarters laid in rubble.

Operation of the refuge ceased. Equipment and staff were gone. Its manager, Al Trout, was alone.

But Ebeling swooped in.

After settling into retiring in the mid-1980s from Morton Thiokol, Ebeling realized he wanted something new to focus on. He walked into the refuge offices in Brigham City and informed Trout that he was there to do whatever was needed and without pay.

With the refuge in ruins, Ebeling coordinated a massive volunteer effort and devoted hundreds of hours to restore the refuge. He rounded up donations, volunteers and the strength to organize them all in five years of intense on-the-ground projects. He set seemingly unrealistic goals for the recovery of the water system — then made them a reality.

Ebeling remained at the heart of the operation. Whether it took donating his saw and blades, operating a piece of heavy equipment, using his airboat, digging a trench for a pipe with his bare hands or using his engineering skills to redesign a headgate, he seemed to always be there.

To Ebeling, the engineering principles of building a rocket weren't all that different from reconstructing a marsh.

"You think bigger on a marsh," he said. "There, you have low pressure and high flows. In a rocket, you deal with low amounts of fuel but high amounts of pressure. The same terms and equations all apply."

It wasn't long before close to a half-million dollars in donated materials, labor and skills began to put the refuge back in business.

—

'Still in love' • Washington, D.C., took notice of his heroic effort. In 1989, Ebeling found himself standing in the White House next to then-President George H. W. Bush to receive the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Award.

Because of his thousands of hours of volunteer work at the refuge, Ebeling was also named the National Wildlife Refuge System Volunteer of the Year for 2012.

Ebeling was nominated for the award by former refuge manager and good friend Trout, who noted Ebeling's more than 20,000 hours of volunteer time and professional talents in his letter of nomination.

As Trout noted in his letter: "Bear River Refuge and the Refuge System owe Bob a debt that can never be repaid."

Ebeling and his wife, Darlene, also spent countless hours greeting visitors to the education center.

Ebeling was the refuge's ambassador "on so many levels," its manager Bob Barrett told The Tribune in 2013. "He works so well with the public. We get visitors from more than 30 countries, and he understands the need to explain to all of them why this is such an important place."

That spring, as Ebeling watched the fruits of his labor produce hundreds of ducks, geese and shore birds, he knew that he was paying off that debt.

For Ebeling, it was all about helping and sharing his passion for the feathered friends he had enjoyed from his earliest memories of tagging along with his father, Ado, more than 80 years ago.

"I'm still in love with the birds," Ebeling said in 2013. "I love the independence of birds. They do what they want when they want. I have a great pride in talking to youngsters about birds. I tell them 'You can't go wrong with the birds. Look how far I got with them.' "

Ebeling eventually overcame his "persistent guilt" over the Challenger disaster, too, in the weeks before his death, according to an NPR story.

Hundreds of NPR readers and listeners responded to a January story about the disaster's anniversary, sending Ebeling messages like: "God didn't pick a loser. He picked Bob Ebeling" and "Bob Ebeling did his job that night… [and] did the right thing and that does not make him a loser. That makes him a winner."

"Ebeling also heard from two of the people who had overruled the engineers back in 1986. Former Thiokol executive Robert Lund and former NASA official George Hardy told him that Challenger was not his burden to bear," NPR wrote upon word of Ebeling's death. "And NASA sent a statement, saying that the deaths of the seven Challenger astronauts served to remind the space agency 'to remain vigilant and to listen to those like Mr. Ebeling who have the courage to speak up.'"

Twitter: @MikeyPanda